Affine plane (incidence geometry)

In geometry, an affine plane is a system of points and lines that satisfy the following axioms:[1]

- Any two distinct points lie on a unique line.

- Given any line and any point not on that line there is a unique line which contains the point and does not meet the given line. (Playfair's axiom)

- There exist four points such that no three are collinear (points not on a single line).

In an affine plane, two lines are called parallel if they are equal or disjoint. Using this definition, Playfair's axiom above can be replaced by:[2]

- Given a point and a line, there is a unique line which contains the point and is parallel to the line.

Parallelism is an equivalence relation on the lines of an affine plane.

Since no concepts other than those involving the relationship between points and lines are involved in the axioms, an affine plane is an object of study belonging to incidence geometry. They are non-degenerate linear spaces satisfying Playfair's axiom.

The familiar Euclidean plane is an affine plane. There are many finite and infinite affine planes. As well as affine planes over fields (and division rings), there are also many non-Desarguesian planes, not derived from coordinates in a division ring, satisfying these axioms. The Moulton plane is an example of one of these.[3]

Finite affine planes

[edit]

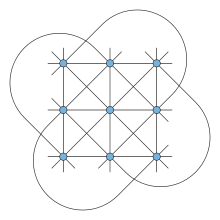

9 points, 12 lines

If the number of points in an affine plane is finite, then if one line of the plane contains n points then:

- each line contains n points,

- each point is contained in n + 1 lines,

- there are n2 points in all, and

- there is a total of n2 + n lines.

The number n is called the order of the affine plane.

All known finite affine planes have orders that are prime or prime power integers. The smallest affine plane (of order 2) is obtained by removing a line and the three points on that line from the Fano plane. A similar construction, starting from the projective plane of order 3, produces the affine plane of order 3 sometimes called the Hesse configuration. An affine plane of order n exists if and only if a projective plane of order n exists (however, the definition of order in these two cases is not the same). Thus, there is no affine plane of order 6 or order 10 since there are no projective planes of those orders. The Bruck–Ryser–Chowla theorem provides further limitations on the order of a projective plane, and thus, the order of an affine plane.

The n2 + n lines of an affine plane of order n fall into n + 1 equivalence classes of n lines apiece under the equivalence relation of parallelism. These classes are called parallel classes of lines. The lines in any parallel class form a partition the points of the affine plane. Each of the n + 1 lines that pass through a single point lies in a different parallel class.

The parallel class structure of an affine plane of order n may be used to construct a set of n − 1 mutually orthogonal latin squares. Only the incidence relations are needed for this construction.

Relation with projective planes

[edit]An affine plane can be obtained from any projective plane by removing a line and all the points on it, and conversely any affine plane can be used to construct a projective plane by adding a line at infinity, each of whose points is that point at infinity where an equivalence class of parallel lines meets.

If the projective plane is non-Desarguesian, the removal of different lines could result in non-isomorphic affine planes. For instance, there are exactly four projective planes of order nine, and seven affine planes of order nine.[4] There is only one affine plane corresponding to the Desarguesian plane of order nine since the collineation group of that projective plane acts transitively on the lines of the plane. Each of the three non-Desarguesian planes of order nine have collineation groups having two orbits on the lines, producing two non-isomorphic affine planes of order nine, depending on which orbit the line to be removed is selected from.

Affine translation planes

[edit]A line l in a projective plane Π is a translation line if the group of elations with axis l acts transitively on the points of the affine plane obtained by removing l from the plane Π. A projective plane with a translation line is called a translation plane and the affine plane obtained by removing the translation line is called an affine translation plane. While in general it is often easier to work with projective planes, in this context the affine planes are preferred and several authors simply use the term translation plane to mean affine translation plane.[5]

An alternate view of affine translation planes can be obtained as follows: Let V be a 2n-dimensional vector space over a field F. A spread of V is a set S of n-dimensional subspaces of V that partition the non-zero vectors of V. The members of S are called the components of the spread and if Vi and Vj are distinct components then Vi ⊕ Vj = V. Let A be the incidence structure whose points are the vectors of V and whose lines are the cosets of components, that is, sets of the form v + U where v is a vector of V and U is a component of the spread S. Then:[6]

- A is an affine plane and the group of translations x → x + w for a vector w is an automorphism group acting regularly on the points of this plane.

Generalization: k-nets

[edit]An incidence structure more general than a finite affine plane is a k-net of order n. This consists of n2 points and nk lines such that:

- Parallelism (as defined in affine planes) is an equivalence relation on the set of lines.

- Every line has exactly n points, and every parallel class has n lines (so each parallel class of lines partitions the point set).

- There are k parallel classes of lines. Each point lies on exactly k lines, one from each parallel class.

An (n + 1)-net of order n is precisely an affine plane of order n.

A k-net of order n is equivalent to a set of k − 2 mutually orthogonal Latin squares of order n.

Example: translation nets

[edit]For an arbitrary field F, let Σ be a set of n-dimensional subspaces of the vector space F2n, any two of which intersect only in {0} (called a partial spread). The members of Σ, and their cosets in F2n, form the lines of a translation net on the points of F2n. If |Σ| = k this is a k-net of order |Fn|. Starting with an affine translation plane, any subset of the parallel classes will form a translation net.

Given a translation net, it is not always possible to add parallel classes to the net to form an affine plane. However, if F is an infinite field, any partial spread Σ with fewer than |F| members can be extended and the translation net can be completed to an affine translation plane.[7]

Geometric codes

[edit]Given the "line/point" incidence matrix of any finite incidence structure, M, and any field, F the row space of M over F is a linear code that we can denote by C = CF(M). Another related code that contains information about the incidence structure is the Hull of C which is defined as:[8]

where C⊥ is the orthogonal code to C.

Not much can be said about these codes at this level of generality, but if the incidence structure has some "regularity" the codes produced this way can be analyzed and information about the codes and the incidence structures can be gleaned from each other. When the incidence structure is a finite affine plane, the codes belong to a class of codes known as geometric codes. How much information the code carries about the affine plane depends in part on the choice of field. If the characteristic of the field does not divide the order of the plane, the code generated is the full space and does not carry any information. On the other hand,[9]

- If π is an affine plane of order n and F is a field of characteristic p, where p divides n, then the minimum weight of the code B = Hull(CF(π))⊥ is n and all the minimum weight vectors are constant multiples of vectors whose entries are either zero or one.

Furthermore,[10]

- If π is an affine plane of order p and F is a field of characteristic p, then C = Hull(CF(π))⊥ and the minimum weight vectors are precisely the scalar multiples of the (incidence vectors of) lines of π.

When π = AG(2, q) the geometric code generated is the q-ary Reed-Muller Code.

Affine spaces

[edit]Affine spaces can be defined in an analogous manner to the construction of affine planes from projective planes. It is also possible to provide a system of axioms for the higher-dimensional affine spaces which does not refer to the corresponding projective space.[11]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Hughes & Piper 1973, p. 82

- ^ Hartshorne 2000, p. 71

- ^ Moulton, Forest Ray (1902), "A Simple Non-Desarguesian Plane Geometry", Transactions of the American Mathematical Society, 3 (2), Providence, R.I.: American Mathematical Society: 192–195, doi:10.2307/1986419, ISSN 0002-9947, JSTOR 1986419

- ^ Moorhouse 2007, p. 11

- ^ Hughes & Piper 1973, p. 100

- ^ Moorhouse 2007, p. 13

- ^ Moorhouse 2007, pp. 21–22

- ^ Assmus & Key 1992, p. 43

- ^ Assmus & Key 1992, p. 208

- ^ Assmus & Key 1992, p. 211

- ^ Lenz 1961, p. 138, but see also Cameron 1991, chapter 3

References

[edit]- Assmus, E.F. Jr.; Key, J.D. (1992), Designs and their Codes, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-41361-9

- Cameron, Peter J. (1991), Projective and Polar Spaces, QMW Maths Notes, vol. 13, London: Queen Mary and Westfield College School of Mathematical Sciences, MR 1153019

- Hartshorne, R. (2000), Geometry: Euclid and Beyond, Springer, ISBN 0387986502

- Hughes, D.; Piper, F. (1973), Projective Planes, Springer-Verlag, ISBN 0-387-90044-6

- Lenz, H. (1961), Grundlagen der Elementarmathematik, Berlin: Deutscher Verlag d. Wiss.

- Moorhouse, Eric (2007), Incidence Geometry (PDF)

Further reading

[edit]- Casse, Rey (2006), Projective Geometry: An Introduction, Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-929886-6

- Dembowski, Peter (1968), Finite Geometries, Berlin: Springer Verlag

- Kárteszi, F. (1976), Introduction to Finite Geometries, Amsterdam: North-Holland, ISBN 0-7204-2832-7

- Lindner, Charles C.; Rodger, Christopher A. (1997), Design Theory, CRC Press, ISBN 0-8493-3986-3

- Lüneburg, Heinz (1980), Translation Planes, Berlin: Springer Verlag, ISBN 0-387-09614-0

- Stevenson, Frederick W. (1972), Projective Planes, San Francisco: W.H. Freeman and Company, ISBN 0-7167-0443-9