Jacob Pavlovich Adler

Jacob Pavlovich Adler | |

|---|---|

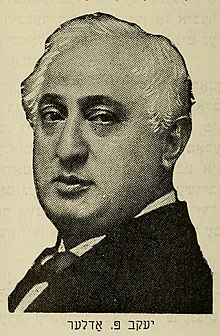

Adler in 1920 | |

| Born | Yankev P. Adler February 12, 1855 |

| Died | April 1, 1926 (aged 71) New York City, U.S. |

| Other names | Jacob P. Adler |

| Occupation | Actor |

| Years active | 1878–1924 |

| Spouses | |

| Children | 9; including Celia, Jay, Julia, Stella, Luther |

| Relatives | Allen Adler (grandson) Francine Larrimore (niece) |

Jacob Pavlovich Adler (Yiddish: יעקבֿ פּאַװלאָװיטש אַדלער; born Yankev P. Adler;[1] February 12, 1855 – April 1, 1926)[2] was a Jewish actor and star of Yiddish theater, first in Odessa, and later in London and in New York City's Yiddish Theater District.[2]

Nicknamed "nesher hagodol",[3][4] ("the Great Eagle", Adler being the German for "eagle"),[4] he achieved his first theatrical success in Odessa, but his career there was rapidly cut short when Yiddish theater was banned in Russia in 1883.[4][5] He became a star in Yiddish theater in London, and in 1889, on his second voyage to the United States, he settled in New York City.[4][6] Adler soon started a company of his own, ushering in a new, more serious Yiddish theater, most notably by recruiting the Yiddish theater's first realistic playwright, Jacob Gordin. Adler scored a great triumph in the title role of Gordin's Der Yiddisher King Lear (The Jewish King Lear), set in 19th-century Russia, which along with his portrayal of Shakespeare's Shylock would form the core of the persona he defined as the "Grand Jew".[4][7]

Nearly all his family went into theater; probably the most famous was his daughter Stella, who taught method acting to, among others, Marlon Brando.[8]

Childhood and youth

[edit]Adler was born in Odessa, Russian Empire (now Ukraine). Adler's father, Feivel (Pavel) Abramovitch Adler, was a (rather unsuccessful) grain merchant. His mother, née Hessye Halperin, was a tall, beautiful woman, originally from a wealthy family in Berdichev. She became estranged from her family after divorcing her first husband (and leaving behind a son) to marry Adler's father. The marriage to a divorcée cost Feivel Adler (and therefore Jacob Adler) his status as a Kohen (priest). His paternal grandfather lived with them for some eight years; he was a pious man, and the family was much more observant of Jewish religious practices during the time he lived with them. However, according to Adler, the real patriarch of the family was his wealthy uncle Aaron "Arke" Trachtenberg, who would later be the model for his portrayal of roles such as Gordin's Jewish King Lear.[9]

Adler grew up with one foot in a traditional Jewish world and one in a more modern, European one. His granddaughter Lulla Rosenfeld writes, "Of the haskala [Jewish Enlightenment] as an organized system of ideas, he probably knew little or nothing."[10] His education was irregular: as the family fortunes rose and fell, he would be sent to cheder (Jewish religious school) or to a Russian language county school, pulled out of school entirely, or have a private tutor for a few months. He wrote that "the sum of my learning was a little arithmetic, some Russian grammar, and a few French phrases."[11]

He grew up with both Jewish and Christian playmates, but also survived one of the Odessa pogroms around 1862.[12] He played hooky; as a 12-year-old he started going to witness public floggings, brandings, and executions of criminals; later he would develop more of an interest in attending courtroom trials.[13] At 14 he began working in a textile factory, and soon rose to a white collar job there at a salary of 10 rubles a month, which would have been decent even for an adult.[14] Still living at home, he began to frequent the disreputable district of Moldovanka. His first brush with stardom was that he briefly became a boxer, known as Yankele Kulachnik, "Jake the Fist". He soon got bored with boxing, but not with his new connections to the "sons of rich fathers, attorneys without diplomas", etc. A good dancer, he became part of a crowd of young toughs who regularly crashed wedding parties. His local celebrity continued, with a reputation as Odessa's best can-can dancer.[15]

He left the factory, becoming a raznoschik, a peddler; his memoir hints at back-door assignations with "servant girls and chambermaids"; by his own description, his life at this point was just a step from a life of crime. Through his uncle Arke, "a hot theater lover", he became interested in the theater, at first in the beauty of Olga Glebova and the cut of Ivan Kozelsky's clothes, but he had the good fortune to be in one of the great theater cities of his time.[16]

At 17 he became the leader of Glebova's claque, was working as a copyist for lawyers, and going out to a theater, a tavern, or a party every night.[17] He would later draw on his own life at this time for his portrayal of Protosov in Tolstoy's The Living Corpse.[18] Over the next few years he had numerous love affairs, and was prevented from a love marriage with one Esther Raizel because his own dubious reputation compounded the taint of his mother's divorce. He survived another pogrom, but his family was financially ruined by the destruction of their possessions and the theft of their money.[19]

In writing about this period in his memoir, Adler mentions attending and admiring performances by Israel Grodner, a Brody singer and improvisational actor who would soon become one of the founders of professional Yiddish theater. A song of Grodner's about an old father turned away by his children would later be the germ of the idea for The Yiddish King Lear. He writes that he would have become a Brody singer, like Grodner, except "I had no voice".[20] This lack of a singing voice would be a major factor in the direction of his acting career: according to Rosenfeld, although Yiddish theater was long dominated by vaudevilles and operettas, "He was the only Yiddish actor to rely entirely on classics and translations of modern European plays."[21]

Sanitar and Inspector

[edit]The outbreak of the Russo-Turkish War brought on universal conscription of young men. At his family's urging, Adler bribed his way into becoming a sanitar, an assistant in the Red Cross Medical Corps. He was selected (apparently on little more than his appearance) by Prince Vladimir Petrovich Meshersky to work at a German hospital in Bender, Moldova, dealing mainly with typhus patients. In his four months there, he became a favorite with the established Jewish families there, and earned a Gold Medal for Outstanding Achievement for his brief service to the Tsar.[22]

Returning to Odessa, he got a job distributing newspapers. This respectable work required getting up at 6 a.m., not good for a carouser. Still, newspaper connection meant that he soon heard of one of the war's other effects: the many Jewish merchants and middlemen war brought to Bucharest were a boon to Abraham Goldfaden's nascent Yiddish theater there. Two of his Odessa acquaintances—Israel Rosenberg, a personable con-man, and Jacob Spivakofsky, scion of a wealthy Jewish family—had become actors there, then had left Goldfaden to found their own company, touring in Moldavia. Adler wrote them to urge them to bring their troupe to Odessa.[23]

Adler managed to leverage a recommendation from Prince Meshersky and another from Avrom Markovich Brodsky—a businessman so successful as to have earned the nickname "the Jewish Tsar"—to get a job as a marketplace inspector for the Department of Weights and Measures, rather unusual for a Jew at that time. His mildly corrupt tenure there gave him good contacts with the police. These would soon come in handy for smoothing over certain problems of a young and unlicensed theater troupe when Rosenberg and Spivakofsky returned from Romania, penniless because the end of the war had meant the collapse of Yiddish theater in the provinces, and ready to start a troupe in Odessa.[24]

Adler aspired to be an actor, but found himself at first serving the troupe more as critic and theoretician, making use of his now-vast knowledge of Russian theater. The first productions (Goldfaden's Grandmother and Granddaughter and Shmendrick) were popular successes, but Adler's own account suggests that they were basically mediocre, and his Uncle Arke was appalled: "Is this theater? No my child, this is a circus."[25]

Acting career

[edit]Lulla Rosenfeld's remark that Adler "...rel[ied] entirely on classics and translations of modern European plays"[21] does not quite tell the whole story. On one hand, he was also responsible for recruiting the Yiddish theater's first naturalistic playwright, Jacob Gordin, and he scored a great triumph in the title role of Gordin's Der Yiddisher King Lear (The Jewish King Lear), set in 19th-century Russia.[26] On the other, until his 50s, he was not hesitant to take advantage of his prowess as a dancer, and even occasionally took on roles that called for some singing, although by all accounts (including his own) this was not his forte.[27]

Ukraine, Moldova, Belarus, Poland, Lithuania, Latvia, Russia

[edit]Adler wrote in his memoir that the passion of his future wife Sonya Oberlander (and of her family) for theater, and their vision of what Yiddish theater could become, kept him in the profession despite his uncle's view. When she was cast by Rosenberg opposite Jacob Spivakovsky in the title role of Abraham Goldfaden's darkly comic operetta Breindele Cossack, she pulled strings so that the role of Guberman would be reassigned to Adler.[28]

His success in the role was cut short by the news that Goldfaden, whose plays they were using without permission, was coming with his troupe to Odesa. Goldfaden's own account says he came there at the urging of his father; Adler attributes it to Rosenberg and Spivakovsky's "enemies". Rosenberg, never the most ethical of men, withdrew his troupe from Odesa to tour the hinterland (soon, though, he would come to an accommodation by which his troupe would be an officially recognized touring company attached to Goldfaden's own troupe).[29] (For greater detail on Adler's time with Rosenberg's company, see Israel Rosenberg.)

By his own account, Adler took a leave of absence from his job to travel with Rosenberg's troupe to Kherson, where he made a successful acting debut as the lover Marcus in The Witch of Botoşani. He overstayed his leave, lost his government post, and the decision to become a full-time actor was effectively made for him.[30] Adler was unhappy that under Tulya Goldfaden there were "No more communistic shares, no more idealistic comradeship". Still, under this same Goldfaden regime he had his first taste of real stardom when people in Chişinău camped in the courtyards awaiting performances. Even the police seemed to have "fallen in love" with the troupe, dressing up the actors in their uniforms at riotous parties after shows, while trying on the troupe's costumes themselves.[31]

Unsatisfied with the low pay, in Kremenchuk Adler led an unsuccessful actors' strike. A series of intrigues almost led to a breakup with Sonya, but ultimately led both back into Rosenberg's troupe and led to their marriage in Poltava. When this particular troupe broke up, the Adlers were among the few players to remain with Rosenberg to form a new one that included the actress who later became famous under the name of Keni Liptzin.[32] In Chernihiv, Adler turned down the opportunity to act in a Russian-language production of Boris Gudonov. Around this time Goldfaden appeared again and, after using an elaborate intrigue to demonstrate to the Adlers that Rosenberg had no loyalty to them, recruited them to his own troupe, which at the time appeared to be headed for a triumphant entry into Saint Petersburg.[33]

All that changed with the assassination of Tsar Alexander II. The mourning for the tsar meant there would be no performances in the capital; in addition the political climate of Russia turned sharply against the Jews. Goldfaden's troupe soldiered on for a time—to Minsk (Belarus), to Bobruisk where they played mainly to Russian soldiers, and to Vitebsk, where he and Sonya ended up having to sue Goldfaden for their pay, and left to rejoin Rosenberg, who was playing in a tent theater in Nizhyn. However, matters there proved even worse: Nizhyn soon fell prey to a pogrom. The troupe managed to avoid bodily harm, partly by convincing the rioters that they were a French theater troupe and partly by making judicious use of the money the Adlers had won in court from Goldfaden.[34]

In Łódź, Adler triumphantly played the title role in Karl Gutzkow's Uriel Acosta, the first of a series of roles through which he developed a persona he would later call "the Grand Jew".[35] After Łódź, they landed in Zhytomyr, under an incompetent investor/director named Hartenstein. They thought they had found "a quiet corner" of the Russian Empire in which "to make a bit of a livelihood", but in fact Hartenstein was simply running through his money.[36]

The financial consequences of the collapse of their company were mitigated by a series of three benefit performances, in coordination with the local Russian-language theater company. Sonya returned to Odessa to give birth to their daughter Rivka; Adler stayed on six weeks in Zhytomyr and had sort of a belated apprenticeship with two Russian character actors of national fame, Borisov and Philipovsky. However, he returned to Odesa thinking that he would most likely leave theater behind.[37]

Late in life, when he looked back at his years acting in Adler and Goldfaden's companies, Adler saw it as merely the "childhood" of his career. He describes his thoughts toward the end of this period, "For three years I had wandered in the cave of the Witch in the clown's rags of Shmendrick and what did I really know of my trade?... If someday I return to the Yiddish theater, let me at least not be so ignorant."[38]

Returning to Odesa, he discovered that no one would employ him in any job other than as an actor. In 1882, he put together a troupe of his own with Keni Liptzin, and brought Rosenberg in as a partner. This troupe toured to Rostov, Taganrog, around Lithuania, to Dünaburg (now Daugavpils, Latvia). Aiming to bring the troupe to Saint Petersburg, they brought back their sometime manager Chaikel Bain. They were in Riga in August 1883 when the news arrived that a total ban was about to be placed on Yiddish theater in Russia.[39]

The troupe were left stranded in Riga. Chaikel Bain took ill and died. With some difficulty, passage to London for the troupe was arranged on a cattle ship, in exchange for entertaining the crew. However, about this time Israel Grodner and his wife Annetta reappeared. Adler wanted to include them in the group headed for London. According to Adler, Rosenberg, who played many of the same roles as Israel Grodner, essentially told Adler "it's him or me". Adler attempted to convince him to change his mind, but insisted on including Grodner in the travel party: Adler considered him one of the best actors in Yiddish theater, a great asset to any performances they would give in London, while he felt Rosenberg lacked depth as an actor. He tried to get Rosenberg to come with them to London, but Rosenberg would not budge.[40]

London

[edit]

Of his time in London, Adler wrote, " if Yiddish theater was destined to go through its infancy in Russia, and in America grew to manhood and success, then London was its school."[41] Adler arrived in London with few contacts. In Whitechapel, the center of Jewish London at that time, he encountered extremes of poverty that he describes as exceeding any he had ever seen in Russia or would ever see in New York. The Chief Rabbi of the British Empire at that time, Dr. Nathan Marcus Adler, was a relative. Adler's father had written him a letter of introduction in Hebrew, but nothing could have been farther from the rabbi's desires than to assist Yiddish-language theater. Nathan Marcus Adler viewed Yiddish as a "jargon" that existed at the expense of both liturgical Hebrew and the English necessary for upward mobility, and his Orthodox Judaism "could not endure so much as a blessing given on stage, for such a blessing would be given in vain"; further, he was afraid that the portrayals of Jews on stage would give aid and comfort to their enemies.[42]

At this time, Yiddish theater in London meant amateur clubs. The arrival of professional Yiddish actors from Russia worked great changes, bringing Yiddish theater in London to a new level and allowing a modest professionalism, though never at much more than a poverty wage. Adler's memoir acknowledges many people who helped him out in various ways. Eventually, with the aid in particular of Sonya's relative Herman Fiedler—a playwright, orchestra leader, and stage manager—the Adlers and the Grodners were able to take over the Prescott Street Club. There they presented generally serious theater to audiences of about 150. Fiedler adapted The Odessa Beggar from Felix Pyat's The Ragpicker of Paris, a tragicomic play written on the eve of the Revolutions of 1848. Adler starred in it, in a role he would continue to play throughout his career.[43]

Two months later, he played Uriel Acosta at the Holborn Theatre to an audience of 500, including the "Jewish aristocrats of the West End". The piety of the London Jews was such that they had to use an (unplayable) cardboard ram's horn so as to avoid blasphemy. Chief Rabbi Adler and his son and eventual successor Hermann Adler were present, and both, especially the younger rabbi, were favorably impressed. There were even mentions in the English-language press.[44]

Playing to small audiences, on tiny stages, in communal troupes where all but the stars had day jobs, and playing only Saturday and Sunday (the pious London Jews would never have tolerated Friday performances), Adler focused on serious theater like never before. However, he and Grodner soon fell out: they wrangled over ideology and over parts, and their verbal duels boiled over into improvised stage dialogue. The Grodners ultimately left to do theater in a series of other locations, notably Paris, but eventually came back to London, where Israel Grodner died in 1887.[45]

By November 1885, Adler had a theatrical club of his own, the Princes Street Club, No. 3 Princes Street (now Princelet Street, E1), purpose-built, financed by a butcher named David Smith. It seated 300; playing every night except Friday, he was earning about £3 s.10 a week, but with a fame well out of proportion to the meagre money. Many of the most prominent figures in Yiddish theater, including Sigmund Mogulesko, David Kessler, Abba and Clara Shoengold, and Sara Heine (the future Sara Adler), gave guest performances when they passed through London.[46]

One of Adler's roles from this period was as the villain Franz Moore in Herman Fiedler's adaptation of Schiller's The Robbers, which introduced Schiller into Yiddish theater. On at least one occasion in 1886, he played both Franz Moore and the play's hero, Franz's brother Karl Moore: in the play they never meet.[47]

In 1886, Adler's daughter Rivka died of croup; Sonya died of an infection contracted while giving birth to their son Abram; meanwhile, he had been carrying on an affair with a young woman, Jenny ("Jennya") Kaiser, who was also pregnant, with his son Charles. Depressed after Sonya's death, he passed up an offer to relocate to the United States, which was taken up instead by Mogulesko and Finkel. In winter 1887, an audience at the Princes Street Club panicked when they thought a simulated stage fire was real; 17 people died in the stampede. While the authorities determined that this was not Adler's fault, and the club was allowed to reopen, the crowds did not return; "the theater," he writes, "was so cold, dark, and empty you could hunt wolves in the gallery."[48]

Adler's affair with Jennya continued; he also took up with a young chorus girl from an Orthodox Jewish family, Dinah Shtettin. His memoir is extremely unclear on the sequence of events, and hints at other affairs at this time. The memoir does make clear that the "hot-blooded" Jennya had little interest in a marriage, while Dinah's father insisted on a marriage, even though he despised Alder and made it clear that he doubted the marriage would last.[49]

Coming to America

[edit]With the aid of a small sum of money from his distant relative the Chief Rabbi, Adler got together the money to travel by steerage to New York, with his infant son Abrom, Alexander Oberlander and his family, Keni and Volodya Liptzin, and Herman Fiedler, among others. Adler did not doubt that the rabbi was glad to see Yiddish actors leaving London. In New York, they promptly discovered that neither Mogulesko and Finkel at the Romanian Opera House nor Maurice Heine at the Oriental Theater had any use for them. They headed on to Chicago, where, after a brief initial success, the troupe fell apart due to a combination of labor disputes and cutthroat competition. The Oberlanders managed to start a restaurant; he and Keni Liptzin headed to New York that autumn, where she managed to sign on at the Romanian Opera House; failing to find a similar situation for himself, he returned to London, drawn back to the charms of both Dinah and Jennya.[50]

He did not remain long in London. After some major successes in Warsaw, which was under Austrian rule, he returned to London in the spring of 1889, and then again to New York, this time to play for Heine at Poole's Theater. After an initial failure in The Odessa Beggar (he writes that the New York audience of the time was not ready for "tragicomedy"), he was a success in the melodrama Moishele Soldat, and "a more worthy success" in Uriel Acosta. This gave him the basis to bring Dinah to America. Their marriage didn't last, though the divorce was amicable: she remarried, to Siegmund Feinman. Adler fell out with Heine, initially over business; at this time Heine's marriage was also falling apart, and Sara Heine would eventually become Sara Adler. Adler went on the road with Boris Thomashefsky, who at the time was pioneering the touring circuit for Yiddish theater in America. They played in Philadelphia and Chicago, where word arrived of an opportunity to take over Poole's, Heine having moved on to the Thalia. Adler returned to New York, where he managed also to win Mogulesko and Kessler away from Heine.[51]

New York

[edit]

Renaming Poole's as the Union Theater, Adler attempted to produce the most serious Yiddish-language theater New York had yet seen in the Yiddish Theater District, with plays such as Scribe's La Juive, Zolotkev's Samson the Great, and Sinckievich's Quo Vadis. However, after Thomashefsky became an enormous popular success in Moses Halevy Horowitz's operetta David ben Jesse at Moishe Finkel's National Theater, the Union Theater temporarily to abandon its highbrow programming and competed head on, with operettas Judith and Holofernes, Titus Andronicus, or the Second Destruction of the Temple, and Hymie in America.[52]

Adler was not content to continue long in this mode, and sought a playwright who could create pieces that would appeal to the Jewish public, while still providing a type of theater he could be proud to perform. He recruited Jacob Gordin, already a well-respected novelist and intellectual, recently arrived in New York and eking out a living as a journalist at the Arbeiter Zeitung, precursor to The Forward. Gordin's first two plays, Siberia and Two Worlds were commercial failures—so much so that Mogulesko and Kessler quit the company—but The Yiddish King Lear, starring Adler and his new wife Sara was such a success that the play eventually transferred to Finkel's larger National Theater. This play (based only very loosely on Shakespeare) played well with the popular audience, but also with Jewish intellectuals who until this time had largely ignored Yiddish Theater, ending for a time the commercial dominance of operettas such as those of Horowitz and Joseph Lateiner. The next year, Gordin's The Wild Man solidified this change in the direction of Yiddish theater.[26]

Over the next decades, Adler would play in (or, in some cases, merely produce) numerous plays by Gordin, but also classics by Shakespeare, Schiller, Lessing; Eugène Scribe's La Juive; dramatizations of George du Maurier's Trilby and Alexandre Dumas, fils' Camille; and the works of modern playwrights such as Gorky, Ibsen, Shaw, Strindberg, Gerhart Hauptmann, Victor Hugo, Victorien Sardou, and Leonid Andreyev. Frequently the works of the great contemporary playwrights—even Shaw, who was writing in English—would be staged in New York in Yiddish years, even decades, before they were ever staged there in English.[53]

Having already famously played Shylock in Shakespeare's The Merchant of Venice on the Yiddish stage at the People's Theater, he played the role again in a 1903 Broadway production, directed by Arthur Hopkins. In this production, Adler spoke his lines in Yiddish while the rest of the cast spoke in English. The New York Times review of Adler's performance was not favorable: in particular his naturalistic acting style was not what audiences of the period expected in a production of Shakespeare.[54] Some other reviews (such as that in Theater magazine) were friendlier;[55] in any event the same production was revived two years later.[56]

Lulla Rosenfeld writes that Henry Irving, the great Shylock before that time, played Shylock as "morally superior to the Christians around him... driven to cruelty only by their more cruel persecutions." In contrast, "Adler scorned justification. Total vindication was his aim." In Adler's own words, "Shylock from the first was governed by pride rather than revenge. He wishes to humble and terrify Antonio for the insult and humiliation he has suffered at his hands. This is why he goes so far as to bring his knife and scales into the court. For Shylock, however, the desired climax was to refuse the pound of flesh with a gesture of divine compassion. When the verdict goes against him, he is crushed because he has been robbed of this opportunity, not because he lusts for Antonio's death. This was my interpretation. This is the Shylock I have tried to show."[4] After his two Broadway triumphs, Adler returned to Yiddish theater.

In the wake of the Kishinev pogrom, Adler went back briefly to Eastern Europe in summer 1903, where he tried to convince various family members to come to America. Although he was greeted as a hero, he was only partially successful in convincing people to leave; his mother, in particular, was determined to finish out her life where she was. (His father had died some years earlier.) He persuaded his sister Sarah Adler to follow him to America as her husband had died of heart disease in Verdun in 1897 and she was raising seven children on her own. She emigrated in 1905.[56]

Returning to New York, he and Thomashefsky jointly leased The People's Theater, intending to use it on different nights of the week. Adler, exhausted from his Russian trip, was often leaving his nights unused, and Thomashefsky offered to buy him out for $10,000 on the condition that he would not return to performing in New York. Adler was so insulted that the two did not speak for months, even though at the time they were living across a courtyard from one another, and could see into each other's St. Mark's Place apartments. Adler decided to perform Tolstoy's The Power of Darkness, and decided that he would do his own translation from Russian to Yiddish. The play was a great success, the first successful production of a Tolstoy play in the U.S., and Thomashefsky was so obviously happy for Adler that their friendship was renewed. Adler followed with equally successful productions of Gordin's dramatization of Tolstoy's Resurrection and the Gordin original The Homeless.[57]

In 1904 Adler had the Grand Theater built in what was to be the Yiddish Theater District at the corner of Bowery and Canal Street, the first purpose-built Yiddish theater in New York. His wife Sara had branched out to do her own plays at the Novelty Theater in Brooklyn, and the family had taken up residence in a four-story brownstone, with an elevator, in the East Seventies. (They would later move one more time, to Riverside Drive.) Around this time Lincoln Steffens wrote a piece saying that Yiddish theater in New York had eclipsed English-language theater in quality.[58]

This golden age was not to last. The years 1905–1908 saw half a million new Jewish immigrants to New York, and once again the largest audience for Yiddish theater was for lighter fare. Adler hung on, but the Thomashefskys were making a fortune at the Thalia; plays with titles like Minke the Servant Girl were far outdrawing fare like Gordin's Dementia Americana (1909). It would be 1911 before Adler scored another major success, this time with Tolstoy's The Living Corpse (also known as Redemption), translated into Yiddish by Leon Kobrin.[59]

In 1919–1920, Adler, despite his own socialist politics, found himself in a labor dispute with the Hebrew Actors' Union; he played that season in London rather than New York. A stroke in 1920 while vacationing in upstate New York nearly ended his acting career, although he continued to appear occasionally, usually as part of a benefit performance for himself, often playing Act I of The Yiddish King Lear: the title character remains seated throughout the entire act. In 1924, he was well enough to perform in the title role of a revival of Gordin's The Stranger, inspired by Tennyson's "Enoch Arden": the character is "a sick and broken man", so the Adler was able to integrate his own physical weakness into the portrayal. However, March 31, 1926, he collapsed suddenly, dying almost instantly.[60]

He is buried in Old Mount Carmel Cemetery in Glendale, Queens.[61]

Family

[edit]Adler was married three times, first to Sophia (Sonya) Oberlander (died 1886), then to Dinah Shtettin (m. 1887- divorced. 1891) and finally to actress Sara Adler (previously Sara Heine) (m. 1891), who survived him by over 25 years.[62]

His and Sonya's daughter Rivkah (Rebecca) died at the age of 3. Sonya died from an infection contracted while giving birth to their son Abram in 1886.[63] Abram's son Allen Adler (1916–1964) was, among other things, the screenwriter of Forbidden Planet.[64] While still married to Sonya, Adler had an affair with Jenny "Jennya" Kaiser, with whom he had a son, stage actor Charles Adler (1886–1966).[65]

Adler and Dinah Shtettin had a daughter, Celia Adler (1889–1979).[66]

He and Sara Heine had six children: the well-known actors Luther (1903–1984) and Stella Adler (1901–1992) and the lesser-known actors Jay (1896–1978), Frances, Julia, and Florence.[67] Jacob and Stella Adler are both members of the American Theater Hall of Fame.[68] Stella was a famous actress and theatre teacher.[69]

His sister Sarah/Soore Adler and her seven children emigrated to New York in 1905. His niece, Francine Larrimore, Sarah's daughter, became a Broadway actress, who also appeared in films. He was the great-uncle of actor Jerry Adler.[70][71]

Memoir

[edit]Adler's memoirs were published in the New York socialist Yiddish-language newspaper Die Varheit in 1916–1919, and briefly resumed in 1925 in an unsuccessful revival of that paper;[10] his granddaughter Lulla Rosenfeld's English translation was published only in 1999. The 1916–1919 portion of the memoir gives a detailed picture of his Russian years. The 1925 portion gives a comparably detailed picture of his time in London,[72] although with some evasions around the relative timing of his relationships with his wife Sonya and with Jennya Kaiser and Dinah Shtettin.[73] It contains only a relatively fragmentary description of his New York career. In the English-language book of these memoirs, Rosenfeld attempts to fill the gaps with her own commentary.[3][72]

Adler writes vividly and with humor. He describes the director Hartenstein as "a young man from Galicia with long hair and short brains, half educated in Vienna, and half an actor", and refers to the poor of Whitechapel as looking as if they "had come out of their mothers already gray and old." Of his early London years, he writes, "We played for a tiny audience, on a stage the size of a cadaver, but we played well, with a drunkenness of happiness."[74]

In a small essay, "Shmendrick, My Mephistopheles", one of the last passages he wrote, Adler describes the last time he saw Shmendrick played, at a memorial for Goldfaden in 1912. Lamenting the choice of play for the memorial—"Goldfaden has written better things"—he nonetheless acknowledges, "that same bitter Shmendrick was our livelihood... I gritted my teeth. I called on the ghosts of Aristophanes, of Shakespeare, of Lope de Vega. I wept and swallowed my own tears... And I cursed the fate that bound me to him... Yet even as I cursed and condemned, the tears rose. For my whole life, my whole past, was before me on that stage... Poor weak first step of our Yiddish theater... I thank you for the happiness you gave us... I thank you Shmendrick—my beloved—my own."[75]

See also

[edit]- Solomon the Wise, 1906 play starring Adler

Notes

[edit]- ^ [Adler 1999] p.xxiii, [Prager 1997]

- ^ a b IMDB biography

- ^ a b Nahshon 2001

- ^ a b c d e f [Rosenfeld 1977]

- ^ [Adler 1999] pp.98–102, 108, 114 et. seq. 222–225.

- ^ [Adler 1999] pp.232–321.

- ^ [Adler 1999], pp. 200–209, 321–325.

- ^ "Stella Adler biography". stellaadler.com. Stella Adler Studio of Acting. Archived from the original on August 29, 2006. Retrieved September 29, 2006.

- ^ [Adler 1999] pp. 5, 7, 9–10; ibid. p. 33 for status as Kohen.

- ^ a b [Adler 1999] p.xxiv

- ^ [Adler 1999] pp. 11–13, 18

- ^ [Adler 1999] pp.6–7

- ^ [Adler 1999] pp.13–14, 30

- ^ [Adler 1999] p.19

- ^ [Adler 1999] pp.19–22; ibid., p.29 for Yankele Kulachnik.

- ^ [Adler 1999] pp.22–24

- ^ [Adler 1999] pp.25, 29, 31

- ^ [Adler 1999] p.32

- ^ [Adler 1999] pp.32–35

- ^ [Adler 1999] p.36

- ^ a b Lulla Rosenfeld, "The Yiddish", New York Times, June 12, 1977. p. 205. (The quotation is in a continuation on p. 36.)

- ^ [Adler 1999] pp. 43–53

- ^ [Adler 1999] pp. 54–55, 59–61

- ^ [Adler 1999] pp.71–73 et.seq., 84–85

- ^ [Adler 1999] pp.76–97, esp. 82, 96

- ^ a b [Adler 1999] pp. 321–325

- ^ Besides the abovementioned "I had no voice" remark, see Stefan Kanfer, The Yiddish Theater’s Triumph Archived September 27, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, City Journal, Spring 2004, which quotes Adler, "I was weak as a singer. I had not a good voice nor, I confess it, a very good ear. But is this why I turned from the operetta to purely dramatic plays? I think not. From my earliest years I leaned toward those plays where the actor works not with jests and comic antics, but with the principles of art; not to amuse the public with tumbling, but to awaken in them and in himself the deepest and most powerful emotions." Accessed online February 21, 2007.

- ^ [Adler 1999] pp. 98–102

- ^ [Adler 1999] pp. 104, 118]

- ^ [Adler 1999] pp.107, 111

- ^ [Adler 1999] p.124

- ^ [Adler 1999] pp.138–157

- ^ [Adler 1999] pp.168–170

- ^ [Adler 1999] pp. 172−179, 189, 192–197

- ^ [Adler 1999] pp.200–209

- ^ [Adler 1999] pp.215–216

- ^ [Adler 1999] pp.218–220

- ^ [Adler 1999] p.218

- ^ [Adler 1999] pp.222–225

- ^ [Adler 1999] pp.93, 225–229

- ^ [Adler 1999], p. 256

- ^ [Adler 1999] pp. 232–236

- ^ [Adler 1999] pp. 239–246

- ^ [Adler 1999] pp.246–247, 257

- ^ [Adler 1999] pp.248–251

- ^ [Adler 1999] pp.265–266, 268

- ^ [Adler 1999] pp.282–283

- ^ [Adler 1999] pp.284–299. Adler does not refer to "Jennya" by name, but translator/commentator Rosenfeld does.

- ^ [Adler 1999] pp. 292–293, 300–304

- ^ [Adler 1999] pp. 299–301, 305–309

- ^ [Adler 1999] pp. 309–315

- ^ [Adler 1999] pp. 316–321

- ^ [Adler 1999], pp. 329–331

- ^ "Yiddish Shylock Viewed..." 1903

- ^ [Adler 1999] p.349 quotes this review: "A striking and original conception, wrought out not only of careful study, but above all from a racial sympathy, an instinctive appreciation of the deeper motives of this profound and complex character." Several other reviews, favorable and unfavorable, are quoted.

- ^ a b [Adler 1999] p. 350

- ^ [Adler 1999] pp.353–355, 359

- ^ [Adler 1999] pp.359, 361

- ^ [Adler 1999] pp.361–364, 367

- ^ [Adler 1999] pp.230 (commentary), 372–378 (commentary)

- ^ Resting Places: The Burial Sites of More than 14000 Famous Persons, Scott Wilson

- ^ [Adler 1999], passim., but esp. pp. 152–154, 261, 294–295, 314, 323

- ^ [Adler 1999] pp.284–286

- ^ [Adler 1999] p.386

- ^ [Adler 1999] p. 291 et. seq.. Adler does not refer to "Jennya" by name, but translator/commentator Rosenfeld does.

- ^ [Adler 1999] p.312

- ^ [Adler 1999] mentions all these children except Florence at least in passing (they are listed in the index, and their relation to him is identified there), but except for Frances and Stella, mentioned in a note on p.230, the book is not explicit that they are Sara's children. The entries for Sara Adler (Jacob Pavlovich Adler at the Internet Broadway Database at IBDb and on Find-a-grave) list her as the mother of these six, but also incorrectly list her as Charles Adler's mother. Her New York Times obituary ("Sarah Adler Dies; Yiddish Stage Star", NYT, April 29, 1953, p. 29), mentions Luther, Stella, Frances, Julia, and "Jack" (presumably Jay) as surviving children by Adler; plus stepsons "Adolph" (presumably Abe) and Charles and stepdaughter Celia; plus her sons Joseph and Max Heine by a former marriage.

- ^ "Theater Hall of Fame members". Retrieved January 9, 2024.

- ^ Gehrcke, Werner (2015). Methoden und Konzepte des Schauspiels: eine Rundreise durch Theorie und Handwerk. Hamburg: disserta Verlag. ISBN 978-3-95935-088-4.

- ^ "Jerry Adler Is In Transitions -- And 'Transparent'". Showriz. August 28, 2017. Retrieved April 23, 2019.

- ^ "The Sunshine Boys lights up Connecticut stage…with two veteran Jewish actors". Jewish Ledger. June 4, 2014. Retrieved April 23, 2019.

- ^ a b [Adler 1999] passim.

- ^ [Adler 1999] p.309 (commentary)

- ^ [Adler 1999] pp.214, 233, 248

- ^ [Adler 1999] pp.365–367

References

[edit]- Adler, Jacob (1999). A Life on the Stage: A Memoir. Translated by Lulla Rosenfeld. New York: Knopf. ISBN 0-679-41351-0. Commentary by Lulla Rosenfeld.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - Adler, Stella. The Art of Acting. ISBN 1-557-833737.

- Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

External links

[edit]- Jacob Pavlovich Adler at the Internet Broadway Database

- Jacob Adler at IMDb Accessed September 29, 2006.

- "Yiddish Shylock Viewed From Ghetto Standpoint". The New York Times. May 31, 1903. p. 10.

- Berkowitz, Joel (2005). Shakespeare on the American Yiddish Stage. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press. ISBN 9781587294082.

- Nahshon, Gad (October 2001). "The Great Eagle: great Yiddish actor-legend, Jacob Adler". The Jewish Post of New York. published online at Jewish-Theatre.com. Retrieved October 1, 2006.

- Prager, Leonard (November 6, 1997). "Shakespeare's The Merchant of Venice in Yiddish". Mendele: Yiddish literature and language. Vol. 07. Archived from the original on July 19, 2008. Retrieved September 29, 2006.

- Rosenfeld, Lulla (June 12, 1977). "The Yiddish". The New York Times. pp. 25, 32.

- "The Jacob P. Adler Family Photograph Collection, 1870s–1930s, Finding Aid" (PDF). library.hunter.cuny.edu. Hunter College.