Maximiliano Hernández Martínez

Maximiliano Hernández Martínez | |

|---|---|

| |

| 27th President of El Salvador | |

| In office 1 March 1935 – 9 May 1944 | |

| Preceded by | Andrés Ignacio Menéndez |

| Succeeded by | Andrés Ignacio Menéndez |

| In office 4 December 1931 – 28 August 1934 Provisional President | |

| Preceded by | Arturo Araujo |

| Succeeded by | Andrés Ignacio Menéndez |

| 21st Vice President of El Salvador | |

| In office 1 March 1931 – 28 August 1934 | |

| President | Arturo Araujo Himself (provisional) |

| Preceded by | Gustavo Vides |

| Succeeded by | Manuel Adriano Vilanova |

| 28th Minister of War, the Navy, and Aviation of El Salvador | |

| In office 1 March 1931 – 1 December 1931 | |

| President | Arturo Araujo |

| Preceded by | Pío Romero Bosque Molina |

| Succeeded by | Salvador López Rochac |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 21 October 1882 San Matías, El Salvador |

| Died | 15 May 1966 (aged 83) Jamastrán, Honduras |

| Manner of death | Assassination (stab wounds) |

| Political party | National Pro Patria Party |

| Spouse | Concepción Monteagudo |

| Children | 8 |

| Alma mater | Polytechnic School University of El Salvador |

| Occupation | Military officer, politician |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | Salvadoran Army |

| Rank | Brigadier general |

| Battles/wars | |

Maximiliano Hernández Martínez (21 October 1882 – 15 May 1966) was a Salvadoran military officer and politician who served as president of El Salvador from 4 December 1931 to 28 August 1934 in a provisional capacity and again in an official capacity from 1 March 1935 until his resignation on 9 May 1944. Martínez was the leader of El Salvador during most of World War II.

Martínez began his military career in the Salvadoran Army, attended the Polytechnic School of Guatemala, and attained the rank of brigadier general by 1919. He ran for president during the 1931 presidential election but withdrew his candidacy and instead endorsed Labor Party candidate Arturo Araujo, who selected Martínez to serve as his vice president and later minister of war. After the Salvadoran military overthrew Araujo in December 1931, the military junta established by the coup plotters, known as the Civic Directory, named Martínez as the country's provisional president. His presidency was not recognized by the United States or other Central American countries until January 1934. The 1931 coup and Martínez's succession to the presidency allowed for the rise of a series of military dictatorships that held onto power in El Salvador until 1979.

Martinez served as president of El Salvador for more than 12 years, making him the longest-serving president in Salvadoran history, and his presidency is sometimes referred to as the Martinato. In January 1932, shortly after assuming the presidency, Martínez crushed a communist and indigenous rebellion; the mass killings committed by the Salvadoran military police following the rebellion's suppression have since been referred to as La Matanza (Spanish for "The Massacre") and resulted in the deaths of between 10,000 and 40,000 peasants. Martínez ruled El Salvador as a totalitarian one-party state led by the National Pro Patria Party, a political party he established in 1933 to support his 1935 presidential election campaign. The 1935, 1939 and 1944 presidential elections were uncontested, and Martínez received every vote cast. Martínez established the Central Reserve Bank and engaged in infrastructure projects such as building the Pan-American Highway in El Salvador, building the Cuscatlán Bridge in central El Salvador, and inaugurating the Nacional Flor Blanca stadium, which held the 1935 Central American and Caribbean Games. The Salvadoran economy almost exclusively relied on coffee production and exports during Martínez's presidency, particularly to Germany and the United States. El Salvador joined the Allied powers of World War II and declared war on Germany, Italy, and Japan in December 1941. Following an attempted coup in April 1944 and massive civil unrest following the execution of the coup's leaders, Martínez resigned as president in May 1944, and he and his family fled the country. In 1966, Martínez was killed in exile at his home in Honduras by his taxi driver following a labor dispute.

Martínez remains a controversial figure in El Salvador. Martínez was described as a fascist and admired the European fascist movements such as those in Germany and Italy. During the lead-up to World War II, he and many of his government officials held sympathies for the Nazis and Axis powers; however, sympathizers were later purged from government after El Salvador joined the war on the side of the Allies. Martínez was a theosophist, believed in the occult, and had a number of religious and personal beliefs that his contemporaries considered unorthodox. During the Salvadoran Civil War (1979–1992), a death squad named after him claimed responsibility for the assassinations of several left-wing politicians.

Early life

[edit]

Maximiliano Hernández Martínez was born on 21 October 1882 in San Matías, El Salvador. His parents were Raymundo Hernández and Petronila Martínez. Martínez[a] earned his bachelor's degree in San Salvador, El Salvador's capital city, after which he enrolled in the Polytechnic School of Guatemala, a military academy where he earned the rank of sub-lieutenant. He returned to El Salvador and attended the Jurisprudence and Social Sciences Faculty at the University of El Salvador; however, he abandoned his studies in favor of pursuing a military career.[4]

Martínez was promoted to the rank of lieutenant on 17 November 1903 and to captain on 23 August 1906. He was promoted to captain major that same year during the Third Totoposte War against Guatemala, where he fought under former Salvadoran president and Brigadier General Tomás Regalado. He was promoted to lieutenant colonel on 6 May 1909 and to colonel on 15 June 1914.[4] The Legislative Assembly promoted Martínez to the rank of brigadier general on 14 July 1919, and President Jorge Meléndez officially sanctioned his promotion on 17 September.[5] Martínez was later employed as a professor at the Captain General Gerardo Barrios Military School[6] and held various positions within the army.[7] He became the military school's director in 1930.[8]

1931 election and vice presidency

[edit]El Salvador had a presidential election in 1931. Every election prior to that date had been held with a pre-designated winner; however, President Pío Romero Bosque decided in spring 1930 to hold free and fair elections for 1931. This led to numerous candidates registering presidential campaigns.[9] Bosque did not endorse any specific candidate.[10] Martínez was among those candidates, resigning his position as second inspector general of the army on 28 May 1930 in order to run for president. Martínez attempted to rally popular support by taking socialist political positions.[11] His campaign was supported by the National Republican Party, a minor political party.[12]

Ultimately, after receiving little support, Martínez withdrew his presidential candidacy and supported Arturo Araujo of the Labor Party, expecting that Araujo would award him the vice presidency.[13] The National Republican Party withdrew its support for Martínez after his withdrawal and endorsement of Araujo.[12] During the election, Araujo won 106,777 votes (46.7 percent),[b] but did not win an outright majority of the votes cast.[15] Martínez's endorsement probably did not sway many voters.[1] As set out in the constitution of El Salvador, the Legislative Assembly convened on 12 February 1931 to select a president, and the legislature unanimously voted in favor of declaring Araujo the election's winner after he promised to reimburse the campaign costs for two other presidential candidates – Alberto Gómez Zárate and Enrique Córdova – in order to satisfy them and their supporters in the legislature.[16]

Araujo then selected Martínez to be his vice president,[13] in part because he believed that Martínez would support his policies[1] and in part in order to ensure the army's loyalty.[17] Additionally, Araujo selected Martínez on the condition that he would marry Araujo's mistress, Concepción "Concha" Monteagudo.[1] Araujo and Martínez both assumed office on 1 March.[4] In addition to the vice presidency, Araujo also appointed Martínez to serve as Minister of War, the Navy, and Aviation (minister of war) and appointed Brigadier General Andrés Ignacio Menéndez to serve as Martínez's deputy.[18] Upon assuming office, Martínez purged military leadership and promoted officers loyal to both himself and the government.[19] Ongoing economic problems caused by the Great Depression and the unrest that followed persisted through Araujo's presidency, leading to Martínez using his position as minister of war to quell protests.[17] While suppressing anti-government protests, Martínez led a group of military officers in June 1931 demanding Araujo repeal the "red code" law, that allowed the president to try and execute military officers for attempting a coup. They also demanded that Araujo reinstate the military's "right to insurrection". Araujo rejected their demands.[20]

Rise to power

[edit]1931 coup and appointment as president

[edit]In late 1931, Araujo attempted to reduce the military's budget in order to improve the government's financial situation, but the army's officers refused to comply with Araujo's proposed budget cut.[21] Araujo's government had failed to pay the military's officers and enlisted men for several months, and on 1 December 1931, Araujo removed Martínez as minister of war, after questioning his loyalty, and replaced him with Salvador López Rochac, Araujo's brother-in-law.[20] On 2 December, due to the government's failure to pay the military's wages[22] and Martínez's removal,[20] a group of junior officers overthrew Araujo, forced him to flee the country to Guatemala,[22] and arrested many of the army's senior officers.[21]

The coup leaders established the Civic Directory, and two of its officers—Colonel Osmín Aguirre y Salinas (who replaced López Rochac as minister of war) and Colonel Joaquín Valdés—assumed the role of co-chairmen of the Civic Directory;[21] the entire Civic Directory itself consisted of twelve military officers from the army, the air force, and the National Guard.[23] The Civic Directory approached Martínez and offered to install him as president of El Salvador, which Martínez accepted.[24] On 4 December, the Civic Directory dissolved itself, declared that Araujo had abandoned the presidency, and officially appointed Martínez to serve as the country's provisional president[3][23] while he was still serving as vice president.[4][25] Although Martínez consolidated his power as provisional president,[26] he did not restore himself as minister of war, instead, appointing Valdés to the office.[24][25] Martínez also appointed Brigadier General Salvador Castaneda Castro as minister of government, promotion, agriculture, labor, sanitation, and charity; Colonel José Asencio Menéndez as sub-secretary of war, the navy, and aviation; Doctor Arturo Ramón Ávila as sub-secretary of foreign relations and justice; Pedro Salvador Fonseca as sub-secretary of finance, public credit, industry, and commerce; and Doctor Benjamín Orozco as sub-secretary of public instruction.[25]

Martínez's role in the coup remains unclear. His supporters claimed that the Civic Directory simply appointed him as provisional president, in accordance with the constitution's provisions for replacing an incumbent in the event that they had left the country, while his opponents claimed that Martínez organized the coup himself.[27] United States ambassador to El Salvador, Charles B. Curtis, believed that the organizers of the coup installed Martínez as a figurehead in order to legitimize the coup and continue exerting power.[28] Joaquín Castro Canizales, a Salvadoran poet and journalist, told American historian Thomas P. Anderson that Martínez had no advanced knowledge that the coup would occur but that he did know that many military officers were dissatisfied with Araujo's government.[29] Brigadier General Salvador Peña Trejo stated that Martínez knew that the military was plotting something but that he did not know any exact details. He further added that Martínez took advantage of the coup in order to assume the presidency.[24] Meanwhile, in a 1968 interview, Araujo himself stated that "it was General Martínez who secretly directed the move that brought him to power [...] I do not believe that other members of the my government, honorable men, were involved". Contemporary Salvadoran leftists also believed that Martínez organized the coup.[30] The Estrella Roja newspaper of the Communist Party of El Salvador praised the coup as "heroic and necessary" but also voiced concern that Martínez would not be able to solve the country's economic crisis.[31]

International recognition

[edit]The Legislative Assembly confirmed Martínez as president of El Salvador in 1932[32] and designated him to serve the remainder of Araujo's term, that would end in 1935.[33] On 8 June 1932, Martínez confirmed that he would stay in office until 1935, after reportedly receiving 2,600 petitions containing thousands of signatures that requested that he do so in April 1932.[34] Although Martínez's government was recognized by the Legislative Assembly, his government did not receive recognition from Costa Rica, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, or the United States due to the terms of the 1923 Central American Treaty of Peace and Amity.[35][36] Article 2 of the treaty stipulated that all its signatories[c] would not recognize governments that assumed power through undemocratic means, such as a coup d'état.[37][38]

In September 1932, Martínez's government received formal recognition from France, Italy, and the United Kingdom.[39][40] Martínez denounced the 1923 treaty on 26 December 1932, three days after Costa Rica had done the same. Costa Rica recognized Martínez's government on 3 January 1934,[41] as did Guatemala, Honduras, and Nicaragua on 24 January.[42][43] The United States recognized Martínez's government on 26 January after Martínez's victory in the 1935 presidential election and after all the signatories to the 1923 treaty had recognized his government.[44][45]

Presidency

[edit]La Matanza

[edit]

Araujo's government had scheduled municipal and legislative elections for 15 December 1931. After his overthrow, the military postponed the municipal elections to be held from 3 to 5 January and the legislative elections to be held from 10 to 12 January 1932. They promised that the elections would be free and fair, and allowed all political parties to participate, including the Communist Party.[46] When the municipal elections took place, municipalities where the Communist Party won had their results suspended by the government.[47] In the subsequent legislative election the following week, after early results indicated a Communist Party victory in the department of San Salvador, the official results published on 21 January announced that three non-communists had won the department's three legislative seats.[48] Violence between the National Guard, communists, and civilians persisted throughout both the municipal and legislative election processes.[49] The government ultimately canceled the results of both elections.[50]

The results of the municipal elections led to the Communist Party believing that it could no longer come to power through democratic means.[51] According to communist Abel Cuenca, the party began plotting a rebellion against Martínez's government on 9 January,[52] and communist Ismael Hernández believed that the United States would support the rebellion, confusing it for a pro-Araujo counterrevolution.[53] A delegation of Communist Party leaders met Valdés and threatened to launch a rebellion unless the government made "substantial contributions to the welfare of the peasants", but the government rejected the communists' demands.[54] On 15 January, the Guatemalan government arrested communist leader Juan Pablo Wainwright for supposedly planning to launch a revolution in Central America.[55] The Salvadoran government arrested communist leaders Farabundo Martí, Mario Zapata, and Alfonso Luna in San Salvador on 19 January,[56] and the arrests may have been prompted by Wainwright's arrest four days prior.[55] The arrests of Martí, Zapata, and Luna were made public the following day.[57]

On 22 January 1932, thousands of peasants led by Francisco Sánchez in western El Salvador—armed with sticks, machetes, and "poor quality" firearms—launched a rebellion against Martínez's government.[58] A group of indigenous Salvadorans known as the Pipils, led by Feliciano Ama, joined the communist rebels because they were sympathetic to their ideology and believed that victory was assured.[59][60] Communist and Pipil rebels attacked and captured the towns and cities of Colón, Jayaque, Juayúa, Izalco, Nahuizalco, Salcoatitán, Sonzacate, Tacuba, and Teotepeque.[56][61] In the process, the rebels killed various politicians, military officers, and landowners; looted and destroyed various buildings; and attempted to sever military communications from the captured towns to the cities of Ahuachapán, Santa Ana, and Sonsonate.[62] The initial rebellion resulted in the deaths of around fifty to seventy rebels, five soldiers, and ten police officers.[63][64] Brigadier General José Tomás Calderón estimated that there were, in total, around 70–80,000 rebels.[65]

On 23 January 1932, Martínez published a manifesto regarding the rebellion in the Diario Oficial, the government's official newspaper. In the manifesto, he stated that it was necessary to "suffocate [the rebels] with a strong hand" ("sofocarlos con mano fuerte") and promised to restore peace and constitutional order.[66] The following day, the government declared martial law, and the army was mobilized to crush the rebellion.[67] By 25 January, the rebellion had been suppressed, and the army had regained control of all the towns captured by the rebels.[68] After the rebellion had been completely suppressed, the army began reprisals against peasants in western El Salvador, especially targeting the Pipil.[69] The indiscriminate killing of civilians continued until mid-February 1932, once the government had determined that the region had been sufficiently "pacified".[70] As the killings disproportionately affected the Pipil population, some scholars have referred to the event as an ethnocide or a genocide.[71][72][73][74]

Many of the rebellion's leaders were executed during the government's mass killings: Sánchez was executed by firing squad on 25 January 1932;[75] Ama was lynched on 28 January;[76] and Martí, Zapata, and Luna were executed by firing squad on 1 February, following a show trial.[77] In total, 10–40,000 people were killed by the military,[78] and the event has since become known as La Matanza (Spanish for "The Massacre").[79][80] To provide clarity in the aftermath of the conflict, the Legislative Assembly issued Legislative Decree No. 121 on 11 July, that granted unconditional amnesty to anyone who committed crimes of any nature in order to "restore order, repress, persecute, punish and capture those accused of the crime of rebellion of this year" ("restablecimiento del orden, represión, persecución, castigo y captura de los sindicados en el delito derebelión").[81]

Martínez's government had knowledge that the rebellion was going to occur, as plans regarding it were discovered on 18 January,[57] and on 21 January, the government had instructed newspapers to report that a rebellion would occur the following day.[82] Cuenca believed that Martínez intentionally allowed the rebellion to happen; he theorized that by preventing social and political change from occurring, Martínez provoked the rebellion, believing that it was doomed to fail.[83] Mauricio de la Selva, a Salvadoran poet and communist, expanded on the theory, believing that Martínez wanted to forcefully crush the communist rebellion in order to win over the United States' recognition of his government and to portray himself as the "champion of anti-communism".[84][85] Doctor Alejandro D. Marroquín argued that Martínez actually feared the Labor Party launching a pro-Araujo rebellion and invasion from Guatemala more than the communist rebellion. Marroquín believed that by Martínez crushing the communist rebellion, he had hoped to deprive Araujo of rebels that could have supported his own counterrevolution.[86]

Economic policies

[edit]Upon assuming office, Martínez's government assumed control over the country's economy in an attempt to mitigate the situation, that ultimately resulted in Araujo's overthrow. In January 1932, Martínez appointed Miguel Tomás Molina as his minister of finance in an effort to establish confidence in the country's financial stability and integrity. Martínez's government then proceeded to make large budget reductions in anticipation of reduced government revenue. The government also reduced interest rates by 40 percent, granted extensions to individuals who were unable to repay their loans,[87] and cut the wages of civil servants — with the exception of military personnel — by 30 percent.[88]

On 23 February 1932, the Salvadoran government suspended repayments of a 1922 loan from American and British lenders, in part because of Martínez's frustration with failing to receive recognition from the United States shortly after he assumed power.[89] After renegotiations in 1932 and 1936, the government resumed repayment of its 1922 loan; however, the government suspended repayments again in 1933 for political reasons and from 1937 to 1946 due to a fall in coffee prices.[90] The loan was fully paid off in 1960.[91] In June 1937, Martínez announced the implementation of the "Martínez Doctrine" to the Legislative Assembly, that held that "the government [will] never again contract new loans", and his quote was commemorated on a bronze plaque inside the Legislative Assembly building.[92] The "Martínez Doctrine" was temporarily suspended in December 1941 during World War II in order for El Salvador to benefit from the Lend-Lease Act, that was promoted by the United States.[93]

On 12 March 1932, Martínez implemented the Moratory Law, that suspended the government's payments of all public and private domestic debts. He passed the law in order to support coffee companies, such as the Salvadoran Coffee Company, that were struggling from the collapse in coffee prices.[7][94] Throughout Martínez's presidency, the Salvadoran economy almost entirely relied on coffee production and exports, specifically Arabica coffee.[95] From 1929 to 1936, Germany was the largest importer of Salvadoran coffee. After the implementation of the "Foreigners' Special Accounts for Inland Payments" policy in Germany, designed to collect debts owed to it by foreign countries, the United States became the largest importer of Salvadoran coffee as the Salvadoran government sought a more financially beneficial trading partner. El Salvador also benefited from free-trade agreements implemented by United States Secretary of State Cordell Hull.[96] In 1937, El Salvador and the United States signed the Commercial Agreement of 1937, that granted El Salvador tariff exemptions on coffee exports.[97] From 1940 to 1944, coffee comprised 98 percent of all Salvadoran exports to the United States.[98] Although El Salvador's exports to Germany decreased in 1936, its imports from Germany significantly increased from 1935 to 1937.[99]

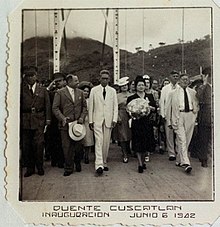

On 30 June 1932, Martínez's government began constructing the 300 kilometers (190 mi) of the Pan-American Highway, that would span the country from east to west.[7] He inaugurated the Estadio Nacional Flor Blanca (now known as the Estadio Jorge "El Mágico" González) in San Salvador on 1 March 1935; the stadium hosted the 3rd Central American and Caribbean Games, that began on 16 March.[100] In 1942, Martínez inaugurated the Cuscatlán Bridge, that crossed the Lempa River in central El Salvador.[101]

Martínez established the Central Reserve Bank on 19 June 1934[102] in order to monopolize the right to issue currency, taking away that right from El Salvador's three largest private banks: the Salvadoran Bank, the Commercial Agricultural Bank, and the Western Bank.[94][103] Martínez's government consulted the Bank of England for advice when establishing the Central Reserve Bank. The bank had the exclusive right to print money, import and export gold, and control foreign exchange rates; it pegged the Salvadoran colón at 2.5 colones to the United States dollar.[94] The bank began issuing currency on 31 August.[102] On 8 January 1935, Martínez established the Mortgage Bank to completely replace the country's three largest private banks' ability to offer loans to coffee companies.[94][102] He also established the Rural Credit Box to give credits to rural peasants.[7]

Elections and constitutional changes

[edit]

In June 1933, Martínez announced his intention to be elected as president of El Salvador in the upcoming 1935 presidential election. He established the National Pro Patria Party (officially the "National Party of the Fatherland") to promote his presidential campaign.[104] He had the previous year, in February 1932, established a network of informants known as the National Pro Patria Legion within the military, police, and intelligence agencies,[105] with the informants themselves known as orejas (Spanish for "ears").[106] The informants spied on and monitored individuals for potential political dissidence, including members of his own government.[107] In 1937, the National Pro Patria Legion was renamed the Civic Guards.[105] In 1941, Martínez later promoted the formation of militias within the National Pro Patria Party.[108] The National Pro Patria Party was the only legal political party in El Salvador, and all politicians in elected or appointed offices had to be members of the party.[109][110]

Martínez resigned as president and vice president on 28 August 1934[4] after seeking permission from the Legislative Assembly to focus on his presidential campaign, and was succeeded by Menéndez in a provisional capacity. Menéndez had been appointed by Martínez as his minister of war[111][112] and was one of Martínez's closest allies.[113] During the election, Martínez won all 329,555 votes cast,[114] as he ran unopposed.[44][113] Martínez was inaugurated for his second term on 1 March 1935.[4]

In August 1938, Martínez announced his intention to seek re-election to a third term as president. Several government officials, such as Molina, Brigadier General Manuel Castaneda, Doctor Maximiliano Brannon (sub-secretary of finance), and Augustín Alfaro (chief audit officer), resigned their positions in protest at Martínez's announcement, accusing him of continuismo.[d] They eventually joined the political opposition.[116] Some military officers—led by Colonel Ascencio Menéndez, Colonel Felipe Calderón, and Lieutenant René Glower Valdivieso—began plotting to overthrow Martínez, but the government discovered the plot in January 1939 and arrested its leaders. They were later exiled to Mexico, together with other opposition leaders.[117]

Martínez repealed the Salvadoran constitution of 1886,[116] and the Legislative Assembly ratified a new constitution on 1 March 1939.[118] Although Martínez's 1939 constitution prohibited re-election just as the 1886 constitution had done, it explicitly granted Martínez an exemption to seek re-election. It also prevented his immediate and extended family from running for office and succeeding him.[74] The same day that the new constitution was ratified, rather than being re-elected through a popular vote, the Legislative Assembly voted to re-elect Martínez to serve a five-year term.[113] Another new constitution was ratified on 1 March 1944 to allow him to be re-elected for a fourth term,[119] and that same day, as in 1939, the Legislative Assembly re-elected him to a fourth term rather than compelling him to be re-elected through the popular vote.[113] His fourth term would have lasted until 1950.[120] Martínez was the last president in Salvadoran history to be re-elected[74] until President Nayib Bukele won re-election in the 2024 presidential election.[121]

Social policies

[edit]In 1932, Martínez revoked the autonomy previously granted to the University of El Salvador, putting it under direct government control. His action led to students and professors protesting against the decision, and in 1934, the government restored the university's autonomy.[122] Martínez revoked the university's autonomy again in 1938, resulting in students going on strike and refusing to attend classes.[117] These protests were suppressed by 1939 without major resistance, and students eventually returned to the university.[118]

In 1934, Martínez implemented laws that discriminated against Arabic, Chinese, and indigenous minorities in the country.[122][123] More discriminatory laws were implemented in 1939, restricting the activities that Arabic, Chinese, and Lebanese minorities could participate in and where they could work.[118] Further laws discriminating against Arabs and Chinese minorities were implemented in 1943.[101] Blacks were also forbidden from entering the country.[123]

The Salvadoran constitution of 1939 implemented several new laws and restrictions on civil liberties. The constitution prohibited the possession of firearms, explosives, and bullets; the consumption of alcoholic beverages and tobacco; and the usage of matches and all types of fossil fuel. The constitution also allowed the government to expropriate private property without prior notice to build new highways or for military purposes. It also mandated a government monopoly over all radio broadcasting in the country.[118] Other laws not in the constitution have also prohibited several civil liberties. Games involving playing cards, dice, ribbons, and thimbles were banned, as were wheel of fortune, roulette, and all games involving luck or random chance. Playing billiards was permitted, but children, students, and servants were forbidden from playing, and laborers were not allowed to play during the weekdays unless it was after 6 p.m.[124] The use of machines in the manufacture of shoes and other types of clothing was banned in an effort to promote the learning of trades.[118]

Ideology and foreign affairs

[edit]In May 1937, Frank P. Corrigan, the United States ambassador to El Salvador, wrote a letter to Hull stating that Martínez had "gained the approval of the greater part of the people", allowed for "free expression of opinion if he considers it well intentioned and not subversive", and believed that Martínez had not become a dictator in an "opprobrious sense".[125] His opinion of Martínez changed after he began openly praising the works of totalitarian governments in Europe and told Hull to work to discourage the "beginning of a Dictatorship" in El Salvador.[126] In mid-1938, Fay Allen Des Portes, the United States ambassador to Guatemala, told Hull that he had received reports that Martínez had "turned Fascist in the letter and the spirit".[116] After Manuel Castaneda left Martínez's government in 1939, he accused Martínez of being the most "anti-democratic" leader in the Americas and that he had shifted the economy in favor of "Nazi-Fascist Imperialism".[99]

Martínez personally admired fascist movements in Germany and Italy.[32] He also believed that corporatism was the ideal system of government and that it should be implemented in El Salvador.[127] Martínez sought to emulate the economic success of European dictators such as Adolf Hitler in Germany and Benito Mussolini in Italy[128] and compared himself to Hitler and Mussolini, believing that the three of them all saved their countries from communism.[129] Martínez permitted Spanish priests with fascist sympathies to instruct schoolchildren and teach them how to perform the Roman salute.[130] In 1936, Martínez's government was among the first to recognize Francisco Franco as the legitimate ruler of Spain during the Spanish Civil War,[127] even before Germany and Italy had done so.[131] Martínez also recognized the independence of Manchukuo, a Japanese puppet state controlling territory in northeastern China.[132] Martínez was personally sympathetic to the Axis powers.[133]

In 1938, the Salvadoran Air Force purchased four Caproni bombers from Italy, with coffee making up part of the payment. The air force initially attempted to purchase the bombers from North American Aviation, but the company refused to accept coffee as payment. Italy sent El Salvador a flight instructor to train new pilots,[134] and additionally, El Salvador sent four pilots to Italy to receive training at the Turin Academy of War. Martínez also purchased thirty-two 75 mm guns from Italy.[135]

Martínez appointed several Nazi sympathizers to some prominent government and military positions.[136] When he established the Mortgage Bank, Martínez appointed German banker Baron Wilhelm von Hundelhausen as the bank's manager and Héctor Herrera, one of Hundelhausen's acquaintances, as the bank's president.[137] Commander W. R. Phillips, a United States military attaché in the Panama Canal Zone, believed that Hundelhausen was promoting Nazi Party meetings in El Salvador and was supporting the Salvadoran government in the hope that it would overthrow the Honduran government, annex the country, and eventually unify Central America under Martínez. Phillips also accused Hundelhausen of being responsible for the spread of pro-German propaganda pamphlets and newspaper advertisements in El Salvador.[138] On 24 April 1938, Martínez appointed German Major General Eberhardt Bohnstedt to serve as the director of the Captain General Gerardo Barrios Military School, as an instructor, and as a military advisor.[139] Colonel Juan Merino, the director of the National Guard, and various other Salvadoran military officers also held Nazi sympathies.[140] Newspapers such as Diario Co Latino, El Diario de Hoy, and La Prensa Gráfica were censored, not only for publishing messages critical of Martínez's government but also for publishing anti-Axis messages. Many journalists were also exiled from the country.[133]

World War II

[edit]

Despite Martínez's personal sympathies with fascism, he continued to reiterate his commitment to democracy, his opposition to totalitarianism, and his support for the United States.[141] Beginning in 1940, he began to crackdown on Nazi activity in El Salvador[142] and even suppressed a fascist demonstration based on the Italian Blackshirts on 10 June 1940, the day that Italy joined World War II on the side of the Axis powers.[143] Although Martínez and many of his government officials supported fascist ideals, the majority of the Salvadoran population did not.[144] In September 1939, both Hundelhausen and Bohnstedt resigned from their positions due to open public opposition to their appointments.[145]

After the outbreak of World War II, Salvadoran exports to Germany diminished significantly, pushing El Salvador to form closer economic ties with the United States.[144] In 1940, the United States sent military advisors to El Salvador to inspect the state of the armed forces,[146] and on 27 March 1941, Martínez appointed American Lieutenant Colonel Robert L. Christian to serve as director of the Captain General Gerardo Barrios Military School. Christian was succeeded by American Lieutenant Colonel Rufus E. Byers on 21 May 1943.[147] On 8 December 1941, after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, El Salvador declared war on Japan. This was followed by declarations of war on both Germany and Italy on 12 December.[148]

In 1942, Martínez dismissed all ministers who held Nazi sympathies.[101] He also ordered the arrests of several German, Japanese, and Italian nationals in El Salvador and interned them at the National Police headquarters.[149] While El Salvador sent laborers to the Panama Canal Zone to maintain the Panama Canal, it did not send any soldiers to fight directly against the Axis powers.[150] Although Martínez aligned El Salvador with the Allied powers, he privately hoped that the Axis powers would win the war.[151][better source needed]

Fall from power

[edit]From 1935 to 1939, five coup attempts were devised to overthrow Martínez. Three were discovered before they could be executed, and the other two were crushed during the attempt.[106] In August 1943, some opposition politicians, military officers, and anti-fascist activists began plotting to overthrow Martínez, but several of the plotters were arrested in late 1943. Shortly afterwards, Ernesto Interiano was killed by the police during an attempted assassination of Martínez in a lone wolf attack.[101]

Palm Sunday Coup

[edit]

On Palm Sunday, 2 April 1944, the 1st and 5th Infantry Divisions and the 2nd Artillery Regiment launched an attempted coup against Martínez's government. The coup was led by some military officers and politicians who had plotted the foiled 1943 coup attempt.[152] The rebel military factions occupied strategic locations in San Salvador and in other major cities and took control of the air force and the YSP radio station.[153] The National Police, the National Guard, and the remainder of the armed forces remained loyal to Martínez. The coup eventually failed due to a lack of leadership[152] and the rebels' failure to capture Martínez.[153]

Throughout April 1944, many of the coup's leaders were given several criminal charges for their roles in the attempted coup. Twenty of the leadership were executed.[152][153] Other leaders who evaded capture fled the country or took refuge in foreign embassies.[152]

Strike of Fallen Arms

[edit]The various military officers and politicians that were executed following the attempted Palm Sunday Coup soon became seen as martyrs by students and other opponents of Martínez.[154] On 28 April 1944, students at the University of El Salvador and doctors from hospitals in San Salvador declared that they would go on strike to protest against the executions until Martínez's government resigned.[155][156] They were later joined by postgraduate, high school, and primary school students.[155] In the ensuing protests, soldiers killed over 100 students, leading to workers, bankers, business owners, and professors joining their protest and declaring a general strike to cripple the country's economy.[156][154]

On 7 May 1944, the police killed José Wright, a United States citizen.[155] After the United States ambassador to El Salvador demanded to know the circumstances surrounding Wright's death,[157] Rodolfo Morales, the minister of governance, resigned. The ambassador later called for Martínez's resignation.[155] On 8 May, Martínez announced his intention to resign as president, which he did on 9 May.[153] Menéndez succeeded Martínez as provisional president[111][158] as he was the first presidential designate — the individual named as a presidential successor in the event the office became vacant.[159]

Death

[edit]On 11 May 1944, two days after issuing his resignation, Martínez and his family fled to Guatemala[155][156] with the assistance of Martínez's brother, Guadeloupe. Afterwards, Martínez and his family moved to Honduras.[160] He returned from exile in 9 July 1955, meeting President Óscar Osorio when his plane landed in San Salvador, but was greeted by protests.[161] When the Legislative Assembly opened discussions on 23 July concerning whether to charge him with crimes committed during his time in office, he fled the country.[162] On 15 May 1966, Martínez was stabbed seventeen times by his taxi driver, Cipriano Morales, in his kitchen in Hacienda Jamastrán, Honduras.[160] Morales killed Martínez over a labor dispute,[158] although police initially suspected that robbery had been the primary motive.[163]

Personal life

[edit]Family

[edit]

Martínez married Araujo's former mistress, Concepción Monteagudo, as one of the conditions he agreed to with Araujo to become his vice president.[1] The couple had eight children: Alberto, Carmen, Esperanza, Marina, Eduardo, Rosa, Gloria, and Maximiliano. Martínez's uncle, Guadalupe Martínez, had helped him enroll in college.[4]

Religious and personal beliefs

[edit]Martínez was a theosophist and a freemason.[79][164][165] He believed in spiritualism[32][44] and the occult,[44][166] and he regularly performed séances at his home.[19] In April 1944, when Luis Chávez y González, the archbishop of San Salvador, asked Martínez to stop the executions of revolutionaries "in the name of God", Martínez responded by telling Chávez, "I am God in El Salvador".[167] Martínez converted to Catholicism in his later life at the insistence of his wife.[168]

Martínez became a vegetarian at the age of 40 and only drank water. He believed that sunlight cast through colored bottles could cure illnesses.[169] When a smallpox epidemic broke out in San Salvador, Martínez ordered the hanging of colored lights in the city in an effort to cure the epidemic.[32] When his youngest son became ill with appendicitis, he refused to allow a surgeon to operate on him. Martínez believed that water in blue bottles hit by sunlight would cure his son's condition, and his son died without receiving proper medical treatment.[167][169] Martínez earned a reputation as a witch doctor for selling remedies that supposedly cured various conditions and circumstances.[169][170] When a group of Americans offered to donate rubber sandals to barefoot Salvadoran schoolchildren, Martínez told them that "It is good for children to go barefoot. That way they better receive the beneficial effluvia of the planet, the vibrations of the Earth. Plants and animals do not wear shoes."[132] Martínez believed in reincarnation.[169][170] During a publicly broadcast lecture at the University of El Salvador on his theosophist beliefs, he stated that "It is a greater crime to kill an ant than a man because when the man dies he becomes reincarnated, while the ant dies definitively".[167] He persisted with many of his beliefs and their associated practices for the rest of his life.[171] Martínez's detractors nicknamed him "El Brujo" (Spanish for "The Witch" or "The Sorcerer") for his beliefs.[19][169][172]

Legacy

[edit]

Martínez was the longest-serving president in Salvadoran history,[32] staying in office for over 12 years.[113] His presidency is sometimes referred to as the Martinato.[173] Martínez was the first of a series of military dictators who held power in El Salvador until the 1979 coup d'état.[174][175][120]

Spanish:

Dicen que fue buen Presidente

porque repartió casas baratas

a los salvadoreños que quedaron...

English:They say he was a good President

because he distributed cheap houses

to the Salvadorans who remained...

The short poem: El general Martínez

by Roque Dalton[176]

Martínez remains a controversial figure in El Salvador. Salvadoran poet Roque Dalton wrote a short poem attacking Martínez titled El general Martínez and named him again in a longer poem following his death titled La segura mano de Dios (The Sure Hand of God).[176] As early as 1948, some history textbooks used in Salvadoran high schools described Martínez's government as a "Nazilike [sic] dictatorship".[177] Jorge Lardé y Larín, a Salvadoran historian and professor at the Captain General Gerardo Barrios Military School, criticized Martínez and his government in his published works, emphasizing that he was not a hero.[178] Many Salvadoran conservatives criticized Martínez's use of force against protestors in April and May 1944.[179]

More recently, historians Héctor Lindo Fuentes, Erik Ching, and Rafael Lara Martínez wrote that those same conservatives "might have cared little" about the mass killings during the anti-communist Matanza.[179] During the 1950s, the Salvadoran military dictatorship that succeeded Martínez often ignored the events of La Matanza as a whole, up until the Cuban Revolution brought Fidel Castro to power in Cuba, after which the government and pro-government newspapers began to promote La Matanza in anti-communist propaganda throughout the 1960s and 1970s.[180] In 2004, the website for the Salvadoran military listed Martínez as one of El Salvador's most important military heroes.[181]

During the Salvadoran Civil War of 1979 to 1992, a far-right death squad operating as the "Anti-Communist Alliance of El Salvador of the Glorious Maximiliano Hernández Martínez Brigade" took their name from Martínez.[182] The group claimed responsibility for the assassinations of various Christian Democrat and Marxist politicians,[183] the assassinations of six Revolutionary Democratic Front leaders in 1980, and other similar killings in 1983.[182] Major Roberto D'Aubuisson, who founded and coordinated multiple death squads during the civil war,[184] led the group at one point, and the Central Intelligence Agency alleged that the death squad had connections to the Nationalist Republican Alliance political party, that D'Aubuisson founded.[185]

Awards and decorations

[edit]During his presidency, Martínez was given the title "Benefactor of the Fatherland" ("Benefactor de la Patria").[4] Instead of styling himself as "Mr. President" ("señor Presidente"), he styled himself as "Master and Leader" ("Maestro y Líder").[186] Martínez was awarded the grand cordon of the Order of the Crown of Italy in 1934[187] followed by the cross of the Order of Boyacá from Colombia in 1936.[188] He was also awarded the grand cross of the Order of the Quetzal by Guatemala in 1937,[189][190] the Order of the Illustrious Dragon by the Japanese puppet state of Manchukuo in China in September 1938,[4][191] the grand cross of the Imperial Order from Japan in October 1938,[192] and the Pan-American Order of Pétion and Bolivar from Haiti in 1940.[193] He was awarded the grand cross and collar of the Order of Isabella the Catholic by Spain in 1940 and 1941, respectively.[194][195]

See also

[edit]- List of heads of state and government with a military background

- List of heads of state or government who have been in exile

Notes

[edit]- ^ Maximiliano Hernández Martínez is commonly referred to in El Salvador as General "Martínez" (using his maternal surname) rather than General "Hernández" (using his paternal surname),[1][2] but he is sometimes referred to as General "Hernández Martínez" (using both of his surnames).[3]

- ^ According to Kenneth Grieb, Araujo won around 101,000 votes.[14]

- ^ The signatories of the 1923 Central American Treaty of Peace and Amity included Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, and Nicaragua.[37]

- ^ Continuismo is the practice of incumbent democratically-elected leaders attempting to extend their term in office beyond legal limitations and restrictions through means such as introducing constitutional amendments or abolishing term limits.[115]

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Anderson 1971, p. 50.

- ^ Haggerty 1990, p. 15.

- ^ a b Bernal Ramírez & Quijano de Batres 2009, p. 109.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Casa Presidencial (c).

- ^ Diario Oficial 1919, p. 1,761.

- ^ Grieb 1971b, p. 153.

- ^ a b c d La Prensa Gráfica 2004.

- ^ Ching 1997, p. 365.

- ^ Anderson 1971, p. 41.

- ^ Lindo Fuentes, Ching & Lara Martínez 2007, p. 80.

- ^ Anderson 1971, p. 42.

- ^ a b Ching 1997, p. 367.

- ^ a b Astilla 1976, p. 34.

- ^ Grieb 1971, p. 153.

- ^ Nohlen 2005, p. 287.

- ^ Astilla 1976, p. 35.

- ^ a b Grieb 1971b, p. 154.

- ^ Diario Oficial 1931a, p. 449.

- ^ a b c Anderson 1971, p. 51.

- ^ a b c Gould & Lauria Santiago 2008, p. 139.

- ^ a b c Grieb 1971b, pp. 154–155.

- ^ a b Astilla 1976, pp. 40–41.

- ^ a b Casa Presidencial (a).

- ^ a b c Anderson 1971, p. 62.

- ^ a b c Diario Oficial 1931b, p. 2,345.

- ^ Astilla 1976, p. 40.

- ^ Astilla 1976, p. 42.

- ^ Grieb 1971b, p. 155.

- ^ Anderson 1971, pp. 61–62.

- ^ Anderson 1971, p. 61.

- ^ Anderson 1971, pp. 80–81.

- ^ a b c d e Haggerty 1990, p. 17.

- ^ Bernal Ramírez & Quijano de Batres 2009, p. 112.

- ^ Grieb 1971b, p. 165.

- ^ Astilla 1976, pp. 45 & 49–50.

- ^ Grieb 1971b, pp. 155–156 & 160.

- ^ a b Woolsey 1934, p. 326.

- ^ Astilla 1976, p. 51.

- ^ Grieb 1971b, p. 168.

- ^ Astilla 1976, pp. 82–83.

- ^ Woolsey 1934, p. 328.

- ^ Grieb 1971a, p. 134.

- ^ Grieb 1971b, p. 170.

- ^ a b c d Anderson 1971, p. 151.

- ^ Woolsey 1934, pp. 325–326.

- ^ Anderson 1971, p. 88.

- ^ Anderson 1971, pp. 88–89.

- ^ Anderson 1971, pp. 90–91.

- ^ Anderson 1971, pp. 88–91.

- ^ Nohlen 2005, p. 277.

- ^ Anderson 1971, p. 91.

- ^ Anderson 1971, p. 86.

- ^ Anderson 1971, p. 92.

- ^ Anderson 1971, pp. 91–92.

- ^ a b Anderson 1971, p. 30.

- ^ a b Luna 1969, p. 48.

- ^ a b Anderson 1971, p. 93.

- ^ Lindo Fuentes, Ching & Lara Martínez 2007, p. 82.

- ^ Anderson 1971, pp. 69–70.

- ^ Astilla 1976, pp. 69–70.

- ^ Lindo Fuentes, Ching & Lara Martínez 2007, pp. 29 & 32.

- ^ Lindo Fuentes, Ching & Lara Martínez 2007, pp. 29–32.

- ^ Lindo Fuentes, Ching & Lara Martínez 2007, p. 33.

- ^ Anderson 1971, p. 136.

- ^ Keogh 1982, p. 13.

- ^ Diario Oficial 1932, p. 121.

- ^ Grieb 1971b, p. 163.

- ^ Lindo Fuentes, Ching & Lara Martínez 2007, p. 37.

- ^ Lindo Fuentes, Ching & Lara Martínez 2007, pp. 37 & 62.

- ^ Lindo Fuentes, Ching & Lara Martínez 2007, p. 38.

- ^ Lindo Fuentes, Ching & Lara Martínez 2007, pp. 62–63 & 246.

- ^ Diario co Latino 2005, p. 5.

- ^ Payés 2007.

- ^ a b c Rauda Zablah 2023.

- ^ Anderson 1971, p. 126.

- ^ Lindo Fuentes, Ching & Lara Martínez 2007, pp. 59 & 351.

- ^ Anderson 1971, pp. 87–88.

- ^ Tulchin & Bland 1992, p. 167.

- ^ a b Beverley 1982, p. 59.

- ^ Bosch 1999, p. 7.

- ^ Cuéllar Martínez 2004, p. 1,087.

- ^ Anderson 1971, p. 94.

- ^ Anderson 1971, pp. 84–85.

- ^ Anderson 1971, p. 85.

- ^ Astilla 1976, p. 72.

- ^ Anderson 1971, pp. 85–86.

- ^ Astilla 1976, pp. 98–99.

- ^ Anderson 1971, p. 90.

- ^ Astilla 1976, pp. 61 & 99–104.

- ^ Astilla 1976, pp. 116–120 & 144–145.

- ^ Bernal Ramírez & Quijano de Batres 2009, p. 128.

- ^ Astilla 1976, p. 132.

- ^ Astilla 1976, pp. 184–185.

- ^ a b c d Anderson 1971, p. 149.

- ^ Astilla 1976, pp. 93–96 & 132–139.

- ^ Astilla 1976, pp. 133–135.

- ^ Astilla 1976, p. 136.

- ^ Astilla 1976, p. 139.

- ^ a b Astilla 1976, p. 149.

- ^ Arteaga 2019.

- ^ a b c d Luna 1969, p. 52.

- ^ a b c Bernal Ramírez & Quijano de Batres 2009, p. 129.

- ^ Lindo Fuentes, Ching & Lara Martínez 2007, p. 83.

- ^ Lauria Santiago & Binford 2004, pp. 59–60.

- ^ a b Holden 2004, p. 63.

- ^ a b Lauria Santiago & Binford 2004, p. 69.

- ^ Lindo Fuentes, Ching & Lara Martínez 2007, p. 215.

- ^ Bernal Ramírez & Quijano de Batres 2009, p. 120.

- ^ Lauria Santiago & Binford 2004, p. 60.

- ^ Lindo Fuentes, Ching & Lara Martínez 2007, pp. 82–83.

- ^ a b Casa Presidencial (b).

- ^ Luna 1969, pp. 50 & 97.

- ^ a b c d e Bernal Ramírez & Quijano de Batres 2009, p. 119.

- ^ Lauria Santiago & Binford 2004, p. 68.

- ^ Baturo & Elgie 2019, p. 79.

- ^ a b c Astilla 1976, p. 148.

- ^ a b Luna 1969, pp. 50–51.

- ^ a b c d e Luna 1969, p. 51.

- ^ Luna 1969, pp. 52–53 & 93.

- ^ a b Ching 1997, p. 357.

- ^ Castillo Vado 2024.

- ^ a b Luna 1969, p. 49.

- ^ a b Lindo Fuentes, Ching & Lara Martínez 2007, p. 281.

- ^ Bernal Ramírez & Quijano de Batres 2009, p. 138.

- ^ Astilla 1976, p. 146.

- ^ Astilla 1976, p. 147.

- ^ a b Astilla 1976, p. 151.

- ^ Astilla 1976, pp. 150–152.

- ^ Astilla 1976, p. 150.

- ^ Astilla 1976, p. 159.

- ^ Luna 1969, p. 50.

- ^ a b Lindo Fuentes, Ching & Lara Martínez 2007, p. 282.

- ^ a b Astilla 1976, pp. 166–167.

- ^ Astilla 1976, pp. 155–157.

- ^ Astilla 1976, p. 158.

- ^ Astilla 1976, p. 162.

- ^ Astilla 1976, pp. 162–163.

- ^ Astilla 1976, pp. 163–164.

- ^ Astilla 1976, p. 161.

- ^ Astilla 1976, pp. 165–166.

- ^ Astilla 1976, pp. 169–171.

- ^ Astilla 1976, p. 169.

- ^ Astilla 1976, p. 167.

- ^ a b Astilla 1976, p. 176.

- ^ Astilla 1976, p. 168.

- ^ Astilla 1976, pp. 179–180.

- ^ Astilla 1976, p. 181.

- ^ Astilla 1976, p. 184.

- ^ Astilla 1976, p. 188.

- ^ Astilla 1976, pp. 188–189.

- ^ Astilla 1976, p. 191.

- ^ a b c d Luna 1969, p. 53.

- ^ a b c d Bernal Ramírez & Quijano de Batres 2009, p. 121.

- ^ a b Lindo Fuentes, Ching & Lara Martínez 2007, p. 84.

- ^ a b c d e Luna 1969, p. 54.

- ^ a b c Astilla 1976, p. 196.

- ^ Bernal Ramírez & Quijano de Batres 2009, p. 125.

- ^ a b Anderson 1971, p. 152.

- ^ McClintock 1985, p. 30.

- ^ a b Bernal Ramírez & Quijano de Batres 2009, p. 123.

- ^ La Prensa Gráfica 1994, p. 502.

- ^ La Prensa Gráfica 1994, p. 503.

- ^ The New York Times 1966, p. 12.

- ^ Anderson 1971, pp. 42 & 50.

- ^ Astilla 1976, pp. 43 & 160.

- ^ Astilla 1976, p. 160.

- ^ a b c Lindo Fuentes, Ching & Lara Martínez 2007, p. 283.

- ^ Astilla 1976, pp. 43–44.

- ^ a b c d e Astilla 1976, p. 43.

- ^ a b Anderson 1971, pp. 50–51.

- ^ Luna 1969, p. 98.

- ^ Lindo Fuentes, Ching & Lara Martínez 2007, p. 63.

- ^ Bernal Ramírez & Quijano de Batres 2009, p. 127.

- ^ Lindo Fuentes, Ching & Lara Martínez 2007, pp. 2 & 82.

- ^ Bosch 1999, pp. 6–8.

- ^ a b Bethell 1998, p. 271.

- ^ Lindo Fuentes, Ching & Lara Martínez 2007, p. 232.

- ^ Lindo Fuentes, Ching & Lara Martínez 2007, p. 233.

- ^ a b Lindo Fuentes, Ching & Lara Martínez 2007, pp. 232–233.

- ^ Lindo Fuentes, Ching & Lara Martínez 2007, pp. 234–236.

- ^ Lindo Fuentes, Ching & Lara Martínez 2007, pp. 241 & 377.

- ^ a b Central Intelligence Agency 1984, p. 23.

- ^ Haggerty 1990, p. 235.

- ^ Central Intelligence Agency 1984, p. 15.

- ^ Central Intelligence Agency 1984, pp. 17 & 23.

- ^ Luna 1969, p. 97.

- ^ The New York Times 1934, p. 13.

- ^ The New York Times 1936, p. 12.

- ^ Monterrosa Cubías 2019, p. 108.

- ^ The New York Times 1937, p. 12.

- ^ The New York Times 1938a, p. 22.

- ^ The New York Times 1938b, p. 8.

- ^ The New York Times 1940, p. 30.

- ^ Boletín Oficial del Estado 1940, p. 5,004.

- ^ Boletín Oficial del Estado 1941, p. 7,004.

Bibliography

[edit]Books

[edit]- Anderson, Thomas P. (1971). Matanza: El Salvador's Communist Revolt of 1932. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska. ISBN 9780803207943. LCCN 78146885. OCLC 1150304117. Retrieved 12 January 2022.

- Baturo, Alexander & Elgie, Robert, eds. (20 June 2019). The Politics of Presidential Term Limits. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780192574343. LCCN 2018964545. OCLC 1104726951. Retrieved 27 January 2024.

- Bernal Ramírez, Luis Guillermo & Quijano de Batres, Ana Elia, eds. (2009). Historia 2 El Salvador [History 2 El Salvador] (PDF). Historia El Salvador (in Spanish). El Salvador: Ministry of Education. ISBN 9789992363683. Retrieved 25 January 2024.

- Bethell, Leslie (13 August 1998). A Cultural History of Latin America: Literature, Music and the Visual Arts in the 19th and 20th Centuries. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521626269. Retrieved 26 July 2024.

- Bosch, Brian J. (1999). The Salvadoran Officer Corps and the Final Offensive of 1981. Jefferson, North Carolina; London: McFarland & Company Incorporated Publishers. ISBN 0786406127. LCCN 99-26678. OCLC 41662421. Retrieved 26 January 2024.

- Ching, Erik K. (1997). From Clientelism to Militarism: The State, Politics and Authoritarianism in El Salvador, 1840–1940. Santa Barbara, California: University of California, Santa Barbara. OCLC 39326756. ProQuest 304330235. Retrieved 28 February 2024.

- Gould, Jeffrey & Lauria Santiago, Aldo A. (2008). To Rise in Darkness: Revolution, Repression, and Memory in El Salvador, 1920–1932. Durham, North Carolina and London: Duke University Press. doi:10.1215/9780822381242. ISBN 9780822342281. OCLC 174501636. Retrieved 28 January 2024.

- Haggerty, Richard A., ed. (1990). El Salvador: A Country Study (2nd ed.). Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress, Federal Research Division. ISBN 9780525560371. LCCN 89048948. OCLC 1044677008. Retrieved 23 February 2020.

- Holden, Robert H. (2004). Armies without Nations: Public Violence and State Formation in Central America, 1821–1960. New York City, New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198036517. LCCN 2002053090. OCLC 1058204367. Retrieved 2 February 2024.

- La Prensa Gráfica (1994). Libro de diamante. Vol. 1. San Salvador: La Prensa Gráfica.

- Lauria Santiago, Aldo A. & Binford, Leigh, eds. (2004). Landscapes of Struggle: Politics, Society, and Community in El Salvador. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: University of Pittsburgh Press. ISBN 9780822972549. LCCN 2003021182. OCLC 604576478. Retrieved 27 July 2020.

- Lindo Fuentes, Héctor; Ching, Erik K. & Lara Martínez, Rafael A. (2007). Remembering a Massacre in El Salvador: The Insurrection of 1932, Roque Dalton, and the Politics of Historical Memory. Albuquerque, New Mexico: University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 9780826336040. OCLC 122424174. Retrieved 26 January 2024.

- McClintock, Michael (1985). The American Connection: State Terror and Popular Resistance in El Salvador. Vol. 1. London, United Kingdom: Zed Books. ISBN 9780862322403. OCLC 1145770950. Retrieved 16 September 2024.

- Monterrosa Cubías, Luis Gerardo (2019). La Sombra del Martinato: Autoritarismo y Lucha Opositora en El Salvador 1931–1945 [The Shadow of the Martinato: Authoritarianism and the Opposition Fight in El Salvador 1931–1945] (PDF) (in Spanish) (1st ed.). San Cristóbal de las Casas, Mexico: National Autonomous University of Mexico. ISBN 9789996110719. OCLC 1260213432. Retrieved 24 January 2024.

- Nohlen, Dieter (2005). Elections in the Americas A Data Handbook Volume 1: North America, Central America, and the Caribbean. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. pp. 270–299. ISBN 9780191557934. OCLC 58051010. Retrieved 27 July 2020.

- Tulchin, Joseph S. & Bland, Gary, eds. (1992). Is There a Transition to Democracy in El Salvador?. Boulder, Colorado: Lynne Rienner Publishers. ISBN 9781555873103. OCLC 25547798. Retrieved 27 January 2024.

Journals

[edit]- Beverley, John (1982). "El Salvador". Social Text (5). Duke University Press: 55–72. doi:10.2307/466334. ISSN 0164-2472. JSTOR 466334. OCLC 5552723453.

- Cuéllar Martínez, Benjamín (October 2004). "El Salvador: De Genocidio en Genocidio" [El Salvador: From Genocide to Genocide]. Estudios Centroamericanos (in Spanish). 59 (672). San Salvador, El Salvador: Central American University: 1, 083–1, 088. doi:10.51378/eca.v59i672.5170. ISSN 0014-1445. Retrieved 27 January 2024.

- Grieb, Kenneth J. (1971a). "The United States and General Jorge Ubico's Retention of Power". Revista de Historia de América (17). Pan American Institute of Geography and History: 119–135. doi:10.1017/S0022216X00001425. ISSN 0034-8325. JSTOR 20138983. OCLC 9969870640.

- Grieb, Kenneth J. (1971b). "The United States and the Rise of General Maximiliano Hernández Martínez". Journal of Latin American Studies. 3 (2). Cambridge University Press: 151–172. doi:10.1017/S0022216X00001425. ISSN 0022-216X. JSTOR 156558. OCLC 9983670644. S2CID 146607906.

- Keogh, Dermot (1982). "El Salvador 1932. Peasant Revolt and Massacre". The Crane Bag. 6 (2). Richard Kearney: 7–14. ISSN 0332-060X. JSTOR 30023895. OCLC 9980267513.

- Luna, David (1969). "Analisis de una Dictadura Fascista Latinoamericana, Maximiliano Hernández Martínez, 1931–1944" [Analysis of a Latin American Fascist Dictatorship, Maximiliano Hernández Martínez, 1931–1944]. Revista la Universidad (in Spanish) (5). San Salvador, El Salvador: University of El Salvador: 41–130. ISSN 0041-8242. OCLC 493370684. Retrieved 26 January 2024.

- Woolsey, L.H. (1934). "The Recognition of the Government of El Salvador". American Journal of International Law. 28 (2). Cambridge University Press: 325–329. doi:10.2307/2190933. ISSN 0002-9300. JSTOR 2190933. OCLC 5545356355.

Newspapers

[edit]- "Alcance al Presupuesto General de 1919 a 1920 de la República de El Salvador" [Scope of the General Budget of 1919 to 1920 of the Republic of El Salvador] (PDF). Diario Oficial (in Spanish). Vol. 87, no. 213. 19 September 1919. pp. 1, 755–1, 770. Retrieved 5 December 2019.

- "Ex-President of El Salvador Is Found Stabbed to Death". The New York Times. Vol. CXV, no. 39, 561. Tegucigalpa, Honduras. 18 May 1966. p. 12. Retrieved 27 January 2024.

- "Italian King Honors Martinez". The New York Times. 15 September 1934. p. 13. Retrieved 25 July 2024.

- "El Salvador President Honored". The New York Times. 12 October 1936. p. 12. Retrieved 25 July 2024.

- "Guatemala Awards Decorations". The New York Times. 25 February 1937. p. 12. Retrieved 25 July 2024.

- "Officials of El Salvador Decorated by Manchukuo". The New York Times. 6 September 1938. p. 22. Retrieved 25 July 2024.

- "Salvador President Decorated". The New York Times. 24 October 1938. p. 8. Retrieved 25 July 2024.

- "Haiti Honors 2 Salvadoreans". The New York Times. 15 December 1940. p. 30. Retrieved 25 July 2024.

- "Gobierno de la Nación" [Government of the Nation] (PDF). Boletín Oficial del Estado (in Spanish). No. 200. 18 July 1940. p. 5,004. Retrieved 25 July 2024.

- "Gobierno de la Nación" [Government of the Nation] (PDF). Boletín Oficial del Estado (in Spanish). No. 256. 13 September 1941. p. 7,004. Retrieved 25 July 2024.

- "Poder Ejecutivo – Secretaria de Gobernación" [Executive Power – Governance Secretary] (PDF). Diario Oficial (in Spanish). Vol. 110, no. 51. 2 March 1931. pp. 449–456. Retrieved 24 January 2024.

- "Poder Ejecutivo – Secretaria de Gobernación" [Executive Power – Governance Secretary] (PDF). Diario Oficial (in Spanish). Vol. 111, no. 269. 5 December 1931. pp. 2, 345–2, 348. Retrieved 25 January 2024.

- "Manifesto del Presidente de la República y Comandante General del Ejército al Pueblo Salvadoreño" [Manifesto of the President of the Republic and Commanding General of the Army to the Salvadoran People] (PDF). Diario Oficial (in Spanish). Vol. 112, no. 19. 23 January 1932. pp. 121–128. Retrieved 26 January 2024.

Web sources

[edit]- Arteaga, Ernesto (1 March 2019). "El Estadio que fue Inaugurado para Maximiliano Hernández Martínez" [The Stadium that was Inaugurated by Maximiliano Hernández Martínez]. La Prensa Gráfica (in Spanish). Retrieved 27 January 2024.

- Astilla, Carmelo Francisco Esmeralda (1976). "The Martinez Era: Salvadoran–American Relations, 1931–1944". Louisiana State University. Ann Arbor, Michigan. OCLC 3809272. Archived from the original on 27 January 2024. Retrieved 27 July 2020.

- Castillo Vado, Houston (5 February 2024). "La Reelección Presidencial en Centroamérica: de Arias a Bukele, Pasando por Ortega y Hernández" [Presidential Re-Election in Central America: From Arias to Bukele, Passing from Ortega and Hernández]. Voice of America (in Spanish). San José, Costa Rica. Retrieved 19 February 2024.

- "El Salvador: Significant Political Actors and Their Interaction" (PDF). Central Intelligence Agency. April 1984. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 January 2017. Retrieved 25 January 2024.

- "General Maximiliano Hernández Martínez". La Prensa Gráfica (in Spanish). 2004. Archived from the original on 4 March 2007. Retrieved 25 January 2024.

- Payés, Txanba (January 2007). "El Salvador. La Insurrección de un Pueblo Oprimido y el Etnocidio Encubierto" [El Salvador. The Insurrection of an Oppressed People and Covert Ethnocide]. Lo Que Somos (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 31 July 2008. Retrieved 27 January 2024.

- "Presidentes de El Salvador – Directorio Civico" [Presidents of El Salvador – Civic Directory]. Casa Presidencial (in Spanish). Government of El Salvador. Archived from the original on 21 April 2009. Retrieved 5 December 2019.

- "Presidentes de El Salvador – General Andrés Ignacio Menéndez" [Presidents of El Salvador – General Andrés Ignacio Menéndez]. Casa Presidencial (in Spanish). Government of El Salvador. Archived from the original on 5 March 2009. Retrieved 28 January 2024.

- "Presidentes de El Salvador – General Maximiliano Hernández Martínez" [Presidents of El Salvador – General Maximiliano Hernández Martínez]. Casa Presidencial (in Spanish). Government of El Salvador. Archived from the original on 23 March 2009. Retrieved 5 December 2019.

- Rauda Zablah, Nelson (11 September 2023). "Re-Election in El Salvador Rhymes with Dictatorship". El Faro. Translated by Kirstein, Jessica. Retrieved 27 January 2024.

- "Salarrue (1898–1975) y Agustín Farabundo Martí (1893–1932)" (PDF). Diario co Latino (in Spanish). No. 783. 15 January 2005. pp. 1–8. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 February 2007. Retrieved 26 January 2024.

Further reading

[edit]- Berk, Jorrit van den; Bak, Hans; Mehring, Frank; Roza, Mathilde (2018). "The Promise of Democracy for the Americas". The Promise of Democracy for the Americas: U.S. Diplomacy and the Meaning(s) of World War II in El Salvador, 1941–1945. Vol. 7. Brill Publishers. pp. 241–264. doi:10.1163/9789004292017_013. ISBN 978-90-04-29201-7. JSTOR 10.1163/j.ctvbqs8h0.15. OCLC 1377133526.

- Dalton, Roque (2014). Las Historias Prohibidas del Pulgarcito [The Prohibited Stories of the Pulgarcito] (PDF) (1st ed.). Melbourne, Australia: Ocean Sur. ISBN 9781921235702. OCLC 984148469.

- "Elections and Events 1900–1934". University of California, San Diego. Archived from the original on 20 July 2020. Retrieved 26 January 2024.

- "Elections and Events 1935–1969". University of California, San Diego. Archived from the original on 20 July 2020. Retrieved 29 January 2024.

- Guzmán, Valeria (8 October 2021). "El Guión del Dictador Moderno y Represor" [The Script of the Modern Dictator and Repressor]. El Faro (in Spanish). Retrieved 27 January 2024.

- Leonard, Thomas M. & Bratzel, John F. (2017). Latin America During World War II. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 9780742537415. LCCN 2006010909. OCLC 65538231.

- Paige, Jeffery M. (1993). "Coffee and Power in El Salvador". Latin American Research Review. 28 (3). Latin American Studies Association: 7–40. doi:10.1017/S0023879100016940. JSTOR 2503609. OCLC 29210109.

External links

[edit]Videos

[edit]- "Grandes Obras del General Martínez" [Great Works of General Martínez]. YouTube (in Spanish). Channel 33. 16 September 2016. Retrieved 27 January 2024.

- "Maximiliano Hernández Martínez. Presidente 1931–1944 (2003)" [Maximiliano Hernández Martínez. President 1931–1944 (2003)]. YouTube (in Spanish). University of Central America. 12 March 2014. Retrieved 26 March 2021.

Websites

[edit]- "Exministros de Defensa" [Former Ministers of Defense]. Armed Forces of El Salvador (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 1 October 2020. Retrieved 4 September 2020.

- "Héroes Militares" [Military Heroes]. Armed Forces of El Salvador (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 22 June 2007. Retrieved 2 February 2024.

- 1882 births

- 1966 deaths

- Politicians assassinated in the 1960s

- 1966 murders in North America

- National presidents assassinated in the 20th century

- 20th-century presidents of El Salvador

- Assassinated military personnel

- Assassinated presidents in North America

- Assassinated Salvadoran politicians

- Deaths by stabbing in Honduras

- Defence ministers of El Salvador

- Fascism in El Salvador

- Fascist politicians

- Perpetrators of Indigenous genocides in North America

- Leaders who took power by coup

- Leaders ousted by a coup

- People from La Libertad Department (El Salvador)

- People murdered in Honduras

- Politicide perpetrators

- Roman Catholic Freemasons

- Salvadoran anti-communists

- Salvadoran exiles

- Salvadoran expatriates in Honduras

- Salvadoran mass murderers

- Salvadoran military personnel

- Salvadoran nationalists

- Salvadoran people murdered abroad

- Salvadoran people of Spanish descent

- Salvadoran Theosophists

- Vice presidents of El Salvador

- World War II political leaders

- Collars of the Order of Isabella the Catholic

- Knights Grand Cross of the Order of Isabella the Catholic

- Order of the Quetzal