African-American literature

This article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2021) |

| Part of a series on |

| African Americans |

|---|

African American literature is the body of literature produced in the United States by writers of African descent. Olaudah Equiano (c. 1745–1797) was an African man who wrote The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, an autobiography published in 1789 that became one of the first influential works about the transatlantic slave trade and the experiences of enslaved Africans. His work was published sixteen years after Phillis Wheatley's work (c. 1753–1784). She was an enslaved African woman who became the first African American to publish a book of poetry, which was published in 1773. Her collection, was titled Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral.

Other prominent writers of the 18th century that helped shape the tone and direction of African American literature were, David Walker (1796–1830) An abolitionist and writer best known for his Appeal to the Coloured Citizens of the World (1829); Frederick Douglass who was a former enslaved person who became a prominent abolitionist, orator, and writer famous for his autobiographies, including Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave (1845); and Harriet Jacobs, an enslaved woman who wrote Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl (1861)

Like most writers, African American writers draw on their every day lived experiences for inspiration on material to write about, therefore African American literature was dominated by autobiographical spiritual narratives throughout much of the 19th century. The genre known as slave narratives in the 19th century were accounts by people who had generally escaped from slavery, about their journeys to freedom and ways they claimed their lives.

The Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s was a great period of flowering in literature and the arts, influenced both by writers who came North in the Great Migration and those who were immigrants from Jamaica and other Caribbean islands. African American writers have been recognized by the highest awards, including the Nobel Prize given to Toni Morrison in 1993. Among the themes and issues explored in this literature are the role of African Americans within the larger American society, African American culture, racism, slavery, and social equality. African-American writing has tended to incorporate oral forms, such as spirituals, sermons, gospel music, blues, or rap.[1]

As African Americans' place in American society has changed over the centuries, so has the focus of African American literature. Before the American Civil War, the literature primarily consisted of memoirs by people who had escaped from enslavement—the genre of slave narratives included accounts of life in enslavement and the path of justice and redemption to freedom. There was an early distinction between the literature of freed slaves and the literature of free blacks born in the North. Free blacks expressed their oppression in a different narrative form. Free blacks in the North often spoke out against enslavement and racial injustices by using the spiritual narrative. The spiritual addressed many of the same themes of enslaved people narratives but has been largely ignored in current scholarly conversation.[2]

At the turn of the 20th century, non-fiction works by authors such as W. E. B. Du Bois and Booker T. Washington debated how to confront racism in the United States. During the Civil Rights Movement, authors such as Richard Wright and Gwendolyn Brooks wrote about issues of racial segregation and black nationalism. Today, African American literature has become accepted as an integral part of American literature, with books such as Roots: The Saga of an American Family by Alex Haley, The Color Purple (1982) by Alice Walker, which won the Pulitzer Prize; and Beloved by Toni Morrison achieving both best-selling and award-winning status.

In broad terms, African American literature can be defined as writings by people of African descent living in the United States. It is highly varied.[3] African American literature has generally focused on the role of African Americans within the larger American society and what it means to be an American.[4] As Princeton University professor Albert J. Raboteau has said, all African American literary study "speaks to the deeper meaning of the African-American presence in this nation. This presence has always been a test case of the nation's claims to freedom, democracy, equality, the inclusiveness of all."[4] African American literature explores the issues of freedom and equality long denied to Blacks in the United States, along with further themes such as African American culture, racism, religion, enslavement, a sense of home,[5] segregation, migration, feminism, and more. African American literature presents experience from an African American point of view. In the early Republic, African American literature represented a way for free blacks to negotiate their identity in an individualized republic. They often tried to exercise their political and social autonomy in the face of resistance from the white public.[6] Thus, an early theme of African American literature was, like other American writings, what it meant to be a citizen in post-Revolutionary America.

Characteristics and themes

[edit]African American literature has both been influenced by the great African diasporic heritage[7] and shaped it in many countries. It has been created within the larger realm of post-colonial literature, although scholars distinguish between the two, saying that "African American literature differs from most post-colonial literature in that it is written by members of a minority community who reside within a nation of vast wealth and economic power."[8]

African American oral culture is rich in poetry, including spirituals, gospel music, blues, and rap. This oral poetry also appears in the African American tradition of Christian sermons, which make use of deliberate repetition, cadence, and alliteration. African American literature—especially written poetry, but also prose—has a strong tradition of incorporating all of these forms of oral poetry.[9] These characteristics do not occur in all works by African American writers.

Some scholars resist using Western literary theory to analyze African American literature. As the Harvard literary scholar Henry Louis Gates, Jr., said, "My desire has been to allow the black tradition to speak for itself about its nature and various functions, rather than to read it, or analyze it, in terms of literary theories borrowed whole from other traditions, appropriated from without."[10] One trope common to African American literature is "signifying". Gates claims that signifying "is a trope in which are subsumed several other rhetorical tropes, including metaphor, metonymy, synecdoche, and irony, and also hyperbole and litotes, and metalepsis."[11] Signifying also refers to the way in which African American "authors read and critique other African-American texts in an act of rhetorical self-definition."[12]

History

[edit]Early African American literature

[edit]African American literature began with slave narratives.[13][14]

African American history predates the emergence of the United States as an independent country, and African American literature has similarly deep roots.[15]

Lucy Terry is the author of the oldest known piece of African American literature, "Bars Fight". Terry wrote the ballad in 1746 after a Native American attack on Deerfield, Massachusetts. She was enslaved in Deerfield at the time of the attack, when many residents were killed and more than 100, mostly women and children, were taken on a forced march overland to Montreal. Some were later ransomed and redeemed by their families or community; others were adopted by Mohawk families, and some girls joined a French religious order. The ballad was first published in 1854, with an additional couplet, in The Springfield Republican[16] and in 1855 in Josiah Holland's History of Western Massachusetts.

The poet Phillis Wheatley (c. 1753–1784) published her book Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral in 1773, three years before American independence. Wheatley was not only the first African American to publish a book, but the first to achieve an international reputation as a writer. Born in Senegal or The Gambia, Wheatley was captured and sold into slavery at around the age of seven. Kidnapped to Massachusetts, she was purchased and owned by a Boston merchant. By the time she was 16, she had mastered her new language of English. Her poetry was praised by many of the leading figures of the American Revolution, including George Washington, who thanked her for a poem written in his honor. Some whites found it hard to believe that a Black woman could write such refined poetry. Wheatley had to defend herself to prove that she had written her own work, so an authenticating preface, or attestation, was provided at the beginning of her book, signed by a list of prominent white male leaders in Massachusetts, affirming her authorship. Some critics cite Wheatley's successful use of this "defensive" authentication document as the first recognition of African American literature.[17] As a result of the skepticism surrounding her work, Poems on Various Subjects was republished with "several introductory documents designed to authenticate Wheatley and her poetry and to substantiate her literary motives."[18][failed verification]

Another early African American author was Jupiter Hammon (1711–1806?), a domestic slave in Queens, New York. Hammon, considered the first published Black writer in America, published his poem "An Evening Thought: Salvation by Christ with Penitential Cries" as a broadside in early 1761. In 1778 he wrote an ode to Phillis Wheatley, in which he discussed their shared humanity and common bonds.[citation needed]

In 1786, Hammon gave his "Address to the Negroes of the State of New York". Writing at the age of 76 after a lifetime of slavery, Hammon said: "If we should ever get to Heaven, we shall find nobody to reproach us for being black, or for being slaves." He also promoted the idea of gradual emancipation as a way to end slavery.[19] Hammon is thought to have been a slave on Long Island until his death. In the 19th century, his speech was later reprinted by several abolitionist groups.

William Wells Brown (1814–1884) and Victor Séjour (1817–1874) produced the earliest works of fiction by African American writers. Séjour was born free in New Orleans (he was a free person of color) and moved to France at the age of 19. There he published his short story "Le Mulâtre" ("The Mulatto") in 1837. It is the first known work of fiction by an African American, but as it was written in French and published in a French journal, it had apparently no influence on later American literature. Séjour never returned to African American themes in his subsequent works.[20]

Brown, on the other hand, was a prominent abolitionist, lecturer, novelist, playwright, and historian. Born into slavery in Kentucky, he was working on riverboats based in St. Louis, Missouri, when he escaped to Ohio. He began to work for abolitionist causes, making his way to Buffalo, New York, and later Boston, Massachusetts. He was a prolific writer, beginning with an account of his escape to freedom and experience under slavery. Brown wrote Clotel; or, The President's Daughter (1853), considered to be the first novel written by an African American. It was based on the persistent (and later confirmed true) rumor that president Thomas Jefferson had fathered a mixed-race daughter with the enslaved woman Sally Hemings, who Jefferson owned. (In the late 20th century, DNA testing affirmed that Jefferson was the father of six children with Hemings; four survived to adulthood, and he gave all their freedom.) The novel was first published in England, where Brown lived for several years.[21]

Frank J. Webb's 1857 novel, The Garies and Their Friends, was also published in England, with prefaces by Harriet Beecher Stowe and Henry, Lord Brougham. It was the first African American fiction to portray passing, that is, a mixed-race person deciding to identify as white rather than black. It also explored northern racism, in the context of a brutally realistic race riot closely resembling the Philadelphia race riots of 1834 and 1835.[22]

The first novel published in the United States by an African American woman was Harriet Wilson's Our Nig (1859).[23] It expressed the difficulties of lives of northern free Blacks. Our Nig was rediscovered and republished by Henry Louis Gates, Jr., in the early 1980s. He labeled the work fiction and argued that it may be the first novel published by an African American.[24] Parallels between Wilson's narrative and her life have been discovered, leading some scholars to argue that the work should be considered autobiographical.[25] Despite these disagreements, Our Nig is a literary work which speaks to the difficult life of free blacks in the North who were indentured servants. Our Nig is a counter-narrative to the forms of the sentimental novel and mother-centered novel of the 19th century.[26]

Another recently discovered work of early African American literature is The Bondwoman's Narrative, which was written by Hannah Crafts between 1853 and 1860. Crafts was a fugitive slave from Murfreesboro, North Carolina. If her work was written in 1853, it would be the first African American novel written in the United States. The novel was published in 2002 with an introduction by Henry Louis Gates, Jr. The work was never published during Crafts' lifetime. Some suggest that she did not have entry into the publishing world.[27] The novel has been described as a style between slave narratives and the sentimental novel.[28] In her novel, Crafts went beyond the genre of the slave narrative. There is some evidence that she read in the library of her master and was influenced by those works: the narrative was serialized and bears resemblances to Charles Dickens' style.[29]– Many critics are still attempting to decode its literary significance and establish its contributions to the study of early African American literature.

Slave narratives

[edit]A genre of African American literature that developed in the middle of the 19th century is the slave narrative, accounts written by fugitive slaves about their lives in the South and, often, after escaping to freedom. They wanted to describe the cruelties of life under slavery, as well as the persistent humanity of the slaves as persons. At the time, the controversy over slavery led to impassioned literature on both sides of the issue, with novels such as Uncle Tom's Cabin (1852) by Harriet Beecher Stowe's representing the abolitionist view of the evils of slavery. Southern white writers produced the "Anti-Tom" novels in response, purporting to truly describe life under slavery, as well as the more severe cruelties suffered by free labor in the North. Examples include Aunt Phillis's Cabin (1852) by Mary Henderson Eastman and The Sword and the Distaff (1853) by William Gilmore Simms.

The slave narratives were integral to African American literature. Some 6,000 former slaves from North America and the Caribbean wrote accounts of their lives, with about 150 of these published as separate books or pamphlets.[30] Slave narratives can be broadly categorized into three distinct forms: tales of religious redemption, tales to inspire the abolitionist struggle, and tales of progress.[30] The tales written to inspire the abolitionist struggle are the most famous because they tend to have a strong autobiographical motif. Many of them are now recognized as the most literary of all 19th-century writings by African Americans, with two of the best-known being Frederick Douglass's autobiography and Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl by Harriet Jacobs (1861).

Jacobs (1813–1897) was born a slave in Edenton, North Carolina and was the first woman to author a slave narrative in the United States. Although her narrative Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl was written under the pseudonym "Linda Brent", the autobiography can be traced through a series of letters from Jacobs to various friends and advisors, most importantly to Lydia Maria Child, the eventual editor of Incidents. The narrative details Jacobs' struggle for freedom, not only for herself, but also for her two children. Jacobs' narrative occupies an important place in the history of African American literature as it discloses through her first hand account specific injustices that black women suffered under slavery, especially their sexual harassment and the threat or actual perpetration of rape as a tool of slavery. Harriet Beecher Stowe was asked to write a foreword for Jacob's book, but refused.[31]

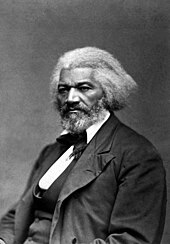

Frederick Douglass

[edit]

Frederick Douglass (c. 1818–1895) first came to public attention in the North as an orator for abolition and as the author of a moving slave narrative. He eventually became the most prominent African American of his time and one of the most influential lecturers and authors in American history.[32]

Born into slavery in Maryland, Douglass eventually escaped and worked for numerous abolitionist causes. He also edited a number of newspapers. Douglass's best-known work is his autobiography, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, which was published in 1845. At the time some critics attacked the book, not believing that a black man could have written such an eloquent work. Despite this, the book was an immediate bestseller.[33] Douglass later revised and expanded his autobiography, which was republished as My Bondage and My Freedom (1855). In addition to serving in a number of political posts during his life, he also wrote numerous influential articles and essays.

Spiritual narratives

[edit]Early African American spiritual autobiographies were published in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Authors of such narratives include James Gronniosaw, John Marrant, and George White. William L. Andrews argues that these early narratives "gave the twin themes of the Afro-American 'pregeneric myth'—knowledge and freedom—their earliest narrative form".[34] These spiritual narratives were important predecessors of the slave narratives which proliferated the literary scene of the 19th century. These spiritual narratives have often been left out of the study of African American literature because some scholars have deemed them historical or sociological documents, despite their importance to understanding African American literature as a whole.[35]

African American women who wrote spiritual narratives had to negotiate the precarious positions of being black and women in early America. Women claimed their authority to preach and write spiritual narratives by citing the Epistle of James, often calling themselves "doers of the word".[36] The study of these women and their spiritual narratives are significant to the understanding of African American life in the Antebellum North because they offer both historical context and literary tropes. Women who wrote these narratives had a clear knowledge of literary genres and biblical narratives. This contributed to advancing their message about African American women's agency and countered the dominant racist and sexist discourse of early American society.

Zilpha Elaw was born in 1790 in America to free parents. She was a preacher for five years in England without the support of a denomination.[37] She published her Memoirs of the Life, Religious Experience, Ministerial Travel and Labours of Mrs. Zilpha Elaw, an American Female of Colour in 1846, while still living in England. Her narrative was meant to be an account of her spiritual experience. Yet some critics argue that her work was also meant to be a literary contribution.[38] Elaw aligns herself in a literary tradition of respectable women of her time who were trying to combat the immoral literature of the time.[39]

Maria W. Stewart published a collection of her religious writings with an autobiographical experience attached in 1879. The publication was called Meditations from the Pen of Mrs. Maria W. Stewart. She also had two works published in 1831 and 1832 titled Religion and the Pure Principles of Morality and Meditations. Maria Stewart was known for her public speeches in which she talked about the role of black women and race relations.[40] Her works were praised by Alexander Crummell and William Lloyd Garrison. Stewart's works have been argued to be a refashioning of the jeremiad tradition and focus on the specific plight of African Americans in America during the period.[41]

Jarena Lee published two religious autobiographical narratives: The Life and Religious Experience of Jarena Lee and Religious Experience and Journal of Mrs. Jarena Lee. These two narratives were published in 1836 and 1849 respectively. Both works spoke about Lee's life as a preacher for the African Methodist Church. But her narratives were not endorsed by the Methodists because a woman preaching was contrary to their church doctrine.[42] Some critics argue that Lee's contribution to African American literature lies in her disobedience to the patriarchal church system and her assertion of women's rights within the Methodist Church.[43]

Nancy Prince was born in 1799, in Newburyport, Massachusetts, and was of African and Native American descent. She turned to religion at the age of 16 in an attempt to find comfort from the trials of her life.[44] She married Nero Prince and traveled extensively in the West Indies and Russia. She became a missionary and in 1841 she tried to raise funds for missionary work in the West Indies, publishing a pamphlet entitled The West Indies: Being a Description of the Islands, Progress of Christianity, Education, and Liberty Among the Colored Population Generally. Later, in 1850, she published A Narrative of the Life and Travels of Mrs. Nancy Prince. These publications were both spiritual narratives and travel narratives.[39] Similar to Jarena Lee, Prince adhered to the standards of Christian religion by framing her unique travel narrative in a Christian perspective.[45] Yet, her narrative poses a counter narrative to the 19th century's ideal of a demure woman who had no voice in society and little knowledge of the world.

Sojourner Truth (1797–1883) was a leading advocate in both the abolitionist and feminist movements in the 19th century. Born Isabella to a wealthy Dutch master in Ulster County, New York, she adopted the name Sojourner Truth after 40 years of struggle, first to attain her freedom and then to work on the mission she felt God intended for her. This new name was to "signify the new person she had become in the spirit, a traveler dedicated to speaking the Truth as God revealed it".[46] Truth played a significant role during the Civil War. She worked tirelessly on several civil rights fronts; she recruited black troops in Michigan, helped with relief efforts for freedmen and women escaping from the South, led a successful effort to desegregate the streetcars in Washington, D.C., and she counseled President Abraham Lincoln. Truth never learned to read or write but in 1850, she worked with Olive Gilbert, a sympathetic white woman, to write the Narrative of Sojourner Truth. This narrative was a contribution to both the slave narrative and female spiritual narratives.

Reconstruction Era Literary Contributors

[edit]After the end of slavery and the American Civil War, a number of African American authors wrote nonfiction works about the condition of African Americans in the United States. Many African American women wrote about the principles of behavior of life during the period.[47] African-American newspapers were a popular venue for essays, poetry and fiction as well as journalism, with newspaper writers like Jennie Carter (1830–1881) developing a large following.[48]

Among the most prominent of post-slavery writers is W. E. B. Du Bois (1868–1963), who had a doctorate in philosophy from Harvard University, and was one of the original founders of the NAACP in 1910. At the turn of the century, Du Bois published a highly influential collection of essays entitled The Souls of Black Folk. The essays on race were groundbreaking and drew from Du Bois's personal experiences to describe how African Americans lived in rural Georgia and in the larger American society.[citation needed] Du Bois wrote: "The problem of the twentieth century is the problem of the color-line",[49] a statement since considered prescient. Du Bois believed that African Americans should, because of their common interests, work together to battle prejudice and inequity. He was a professor at Atlanta University and later at Howard University.

Another prominent author of this period is Booker T. Washington (1856–1915), who in many ways represented opposite views from Du Bois. Washington was an educator and the founder of the Tuskegee Institute, a historically black college in Alabama. Among his published works are Up From Slavery (1901), The Future of the American Negro (1899), Tuskegee and Its People (1905), and My Larger Education (1911). In contrast to Du Bois, who adopted a more confrontational attitude toward ending racial strife in America, Washington believed that Blacks should first lift themselves up and prove themselves the equal of whites before asking for an end to racism. While this viewpoint was popular among some Blacks (and many whites) at the time, Washington's political views would later fall out of fashion.[citation needed]

Frances E. W. Harper (1825–1911) wrote four novels, several volumes of poetry, and numerous stories, poems, essays and letters. Born to free parents in Baltimore, Maryland, Harper received an uncommonly thorough education at her uncle, William Watkins' school. In 1853, publication of Harper's Eliza Harris, which was one of many responses to Harriet Beecher Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin, brought her national attention. Harper was hired by the Maine Anti-Slavery Society and in the first six weeks, she managed to travel to twenty cities, giving at least thirty-one lectures.[50] Her book Poems on Miscellaneous Subjects, a collection of poems and essays prefaced by William Lloyd Garrison, was published in 1854 and sold more than 10,000 copies within three years. Harper was often characterized as "a noble Christian woman" and "one of the most scholarly and well-read women of her day", but she was also known as a strong advocate against slavery and the post-Civil War repressive measures against blacks.

Elizabeth Keckley (1818–1907) was a former slave who managed to establish a successful career as a dressmaker who catered to the Washington political elite after obtaining her freedom. However, soon after publishing Behind the Scenes; or, Thirty Years as a Slave and Four Years in the White House, she lost her job and found herself reduced to doing odd jobs. Although she acknowledged the cruelties of her enslavement and her resentment towards it, Keckley chose to focus her narrative on the incidents that "moulded her character", and on how she proved herself "worth her salt".[51] Behind the Scenes details Keckley's life in slavery, her work for Mary Todd Lincoln and her efforts to obtain her freedom. Keckley was also deeply committed to programs of racial improvement and protection and helped found the Home for Destitute Women and Children in Washington, D.C., as a result. In addition to this, Keckley taught at Wilberforce University in Ohio.

Josephine Brown (born 1839), the youngest child of abolitionist and author William Wells Brown, wrote a biography of her father, Biography of an American Bondman, By His Daughter. Brown wrote the first ten chapters of the narrative while studying in France, as a means of satisfying her classmates' curiosity about her father. After returning to America, she discovered that the narrative of her father's life, written by him, and published a few years before, was out of print and thus produced the rest of the chapters that constitute Biography of an American Bondman. Brown was a qualified teacher but she was also extremely active as an advocate against slavery.

Although not a US citizen, the Jamaican Marcus Garvey (1887–1940), was a newspaper publisher, journalist, and activist for Pan Africanism who became well known in the United States. He founded the Universal Negro Improvement Association and African Communities League (UNIA). He encouraged black nationalism and for people of African ancestry to look favorably upon their ancestral homeland. He wrote a number of essays published as editorials in the UNIA house organ, the Negro World newspaper. Some of his lecture material and other writings were compiled and published as nonfiction books by his second wife Amy Jacques Garvey as the Philosophy and Opinions of Marcus Garvey Or, Africa for the Africans (1924) and More Philosophy and Opinions of Marcus Garvey (1977).[citation needed]

Paul Laurence Dunbar, who often wrote in the rural, black dialect of the day, was the first African American poet to gain national prominence.[52] His first book of poetry, Oak and Ivy, was published in 1893. Much of Dunbar's work, such as When Malindy Sings (1906), which includes photographs taken by the Hampton Institute Camera Club and Joggin' Erlong (1906) provide revealing glimpses into the lives of rural African Americans of the day. Though Dunbar died young, he was a prolific poet, essayist, novelist (among them The Uncalled, 1898 and The Fanatics, 1901) and short story writer.

Other African American writers also rose to prominence in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Among these is Charles W. Chesnutt, a well-known short story writer, novelist, and essayist. Mary Weston Fordham published Magnolia Leaves in 1897, a book of poetry on religious, spiritual, and occasionally feminist themes with an introduction by Booker T. Washington.[citation needed]

Harlem Renaissance

[edit]The Harlem Renaissance from 1920 to 1940 was a flowering of African American literature and art. Based in the African American community of Harlem in New York City, it was part of a larger flowering of social thought and culture. Numerous Black artists, musicians and others produced classic works in fields from jazz to theater.

Among the most renowned writers of the renaissance is poet Langston Hughes, whose first work was published in The Brownies' Book in 1921.[53] He first received attention in the 1922 publication The Book of American Negro Poetry. Edited by James Weldon Johnson, this anthology featured the work of the period's most talented poets, including Claude McKay, who also published three novels, Home to Harlem, Banjo and Banana Bottom, a nonfiction book, Harlem: Negro Metropolis, and a collection of short stories. In 1926, Hughes published a collection of poetry, The Weary Blues, and in 1930 a novel, Not Without Laughter. He wrote "The Negro Speaks of Rivers" as a young teen. His single, most recognized character is Jesse B. Simple, a plainspoken, pragmatic Harlemite whose comedic observations appeared in Hughes's columns for the Chicago Defender and the New York Post. Simple Speaks His Mind (1950) is a collection of stories about centering on Simple published in book form. Until his death in 1967, Hughes published nine volumes of poetry, eight books of short stories, two novels and a number of plays, children's books and translations.

Another notable writer of the renaissance is novelist Zora Neale Hurston, author of the classic novel Their Eyes Were Watching God (1937). Although Hurston wrote 14 books that ranged from anthropology to short stories to novel-length fiction, her writings fell into obscurity for decades. Her work was rediscovered in the 1970s through Alice Walker's 1975 article "In Search of Zora Neale Hurston", published in Ms. and later retitled "Looking for Zora".[54][55] Walker found in Hurston a role model for all female African American writers.[citation needed]

While Hurston and Hughes are the two most influential writers to come out of the Harlem Renaissance, a number of other writers also became well known during this period. They include Jean Toomer, author of Cane, a famous collection of stories, poems, and sketches about rural and urban Black life, and Dorothy West, whose novel The Living is Easy examined the life of an upper-class Black family. Another popular renaissance writer is Countee Cullen, who in his poems described everyday black life (such as a trip he made to Baltimore that was ruined by a racial insult). Cullen's books include the poetry collections Color (1925), Copper Sun (1927), and The Ballad of the Brown Girl (1927). Frank Marshall Davis's poetry collections Black Man's Verse (1935) and I am the American Negro (1937), published by Black Cat Press, earned him critical acclaim. Author Wallace Thurman also made an impact with his novel Thinterracial heerry: A Novel of Negro Life (1929), which focused on interracial prejudice between lighter-skinned and darker-skinned African Americans.[citation needed]

The Harlem Renaissance marked a turning point for African American literature. Prior to this time, books by African Americans were primarily read by other Black people. With the renaissance, though, African American literature—as well as black fine art and performance art—began to be absorbed into mainstream American culture.[citation needed]

Civil Rights Movement era

[edit]A large migration of African Americans began during World War I, hitting its high point during World War II. During this Great Migration, Black people left the racism and lack of opportunities in the American South and settled in northern cities such as Chicago, where they found work in factories and other sectors of the economy.[56]

This migration produced a new sense of independence in the Black community and contributed to the vibrant Black urban culture seen during the Harlem Renaissance. The migration also empowered the growing Civil Rights Movement, which made a powerful impression on Black writers during the 1940s, '50s and '60s. Just as Black activists were pushing to end segregation and racism and create a new sense of Black nationalism, so too were Black authors attempting to address these issues with their writings.[citation needed]

One of the first writers to do so was James Baldwin, whose work addressed issues of race and sexuality. Baldwin, who is best known for his novel Go Tell It on the Mountain, wrote deeply personal stories and essays while examining what it was like to be both Black and homosexual at a time when neither of these identities was accepted by American culture. In all, Baldwin wrote nearly 20 books, including such classics as Another Country and The Fire Next Time.[citation needed]

Baldwin's idol and friend was author Richard Wright, whom Baldwin called "the greatest Black writer in the world for me". Wright is best known for his novel Native Son (1940), which tells the story of Bigger Thomas, a Black man struggling for acceptance in Chicago. Baldwin was so impressed by the novel that he titled a collection of his own essays Notes of a Native Son, in reference to Wright's novel. However, their friendship fell apart due to one of the book's essays, "Everybody's Protest Novel," which criticized Native Son for lacking credible characters and psychological complexity. Among Wright's other books are the autobiographical novel Black Boy (1945), The Outsider (1953), and White Man, Listen! (1957).[citation needed]

The other great novelist of this period is Ralph Ellison, best known for his novel Invisible Man (1952), which won the National Book Award in 1953. Even though he did not complete another novel during his lifetime, Invisible Man was so influential that it secured his place in literary history. After Ellison's death in 1994, a second novel, Juneteenth (1999), was pieced together from the 2,000-plus pages he had written over 40 years. A fuller version of the manuscript was published as Three Days Before the Shooting (2010).[citation needed]

The Civil Rights time period also saw the rise of female Black poets, most notably Gwendolyn Brooks, who became the first African American to win the Pulitzer Prize when it was awarded for her 1949 book of poetry, Annie Allen. Along with Brooks, other female poets who became well known during the 1950s and '60s are Nikki Giovanni and Sonia Sanchez.[citation needed]

During this time, a number of playwrights also came to national attention, notably Lorraine Hansberry, whose play A Raisin in the Sun focuses on a poor Black family living in Chicago. The play won the 1959 New York Drama Critics' Circle Award. Another playwright who gained attention was Amiri Baraka, who wrote controversial off-Broadway plays. In more recent years, Baraka became known for his poetry and music criticism.[citation needed]

It is also worth noting that a number of important essays and books about human rights were written by the leaders of the Civil Rights Movement. One of the leading examples of these is Martin Luther King Jr.'s "Letter from Birmingham Jail".[citation needed]

Recent history

[edit]Beginning in the 1970s, African American literature reached the mainstream as books by Black writers continually achieved best-selling and award-winning status. This was also the time when the work of African American writers began to be accepted by academia as a legitimate genre of American literature.[57]

As part of the larger Black Arts Movement, which was inspired by the Civil Rights and Black Power movements, African American literature began to be defined and analyzed. A number of scholars and writers are generally credited with helping to promote and define African American literature as a genre during this time period, including fiction writers Toni Morrison and Alice Walker and poet James Emanuel.[citation needed]

James Emanuel took a major step toward defining African American literature when he edited (with Theodore Gross) Dark Symphony: Negro Literature in America (1968), a collection of black writings released by a major publisher.[58] This anthology, and Emanuel's work as an educator at the City College of New York (where he is credited with introducing the study of African-American poetry), heavily influenced the birth of the genre.[58] Other influential African American anthologies of this time included Black Fire: An Anthology of Afro-American Writing, edited by LeRoi Jones (now known as Amiri Baraka) and Larry Neal in 1968; The Negro Caravan, co-edited by Sterling Brown, Arthur P. Davis and Ulysses Lee in 1969; and We Speak As Liberators: Young Black Poets — An Anthology, edited by Orde Coombs and published in 1970.

Toni Morrison, meanwhile, helped promote Black literature and authors in the 1960s and '70s when she worked as an editor for Random House, where she edited books by such authors as Toni Cade Bambara and Gayl Jones. Morrison herself would later emerge as one of the most important African American writers of the 20th century. Her first novel, The Bluest Eye, was published in 1970. Among her most famous novels is Beloved, which won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction in 1988. This story describes a slave who found freedom but killed her infant daughter to save her from a life of slavery. Another important Morrison novel is Song of Solomon, a tale about materialism, unrequited love, and brotherhood. Morrison is the first African American to win the Nobel Prize in Literature.

In the 1970s, novelist and poet Alice Walker wrote a famous essay that brought Zora Neale Hurston and her classic novel Their Eyes Were Watching God back to the attention of the literary world. In 1982, Walker won both the Pulitzer Prize and the American Book Award for her novel The Color Purple. An epistolary novel (a book written in the form of letters), The Color Purple tells the story of Celie, a young woman who is sexually abused by her stepfather and then is forced to marry a man who physically abuses her. The novel was later made into a film by Steven Spielberg.

The 1970s also saw African American books by and about African American life topping the bestseller lists. Among the first to do so was Roots: The Saga of an American Family by Alex Haley. A fictionalized account of Haley's family history—beginning with the kidnapping of his ancestor Kunta Kinte in Gambia through his life as a slave in the United States—Roots won the Pulitzer Prize and became a popular television miniseries. Haley also wrote The Autobiography of Malcolm X in 1965.

Other important writers in recent years include literary fiction writers Gayl Jones, Rasheed Clark, Ishmael Reed, Jamaica Kincaid, Randall Kenan, and John Edgar Wideman. African American poets have also garnered attention. Maya Angelou read a poem at Bill Clinton's inauguration, Rita Dove won a Pulitzer Prize and served as Poet Laureate of the United States from 1993 to 1995, and Cyrus Cassells's Soul Make a Path through Shouting was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize in 1994. Cassells is a recipient of the William Carlos Williams Award. Natasha Trethewey won the 2007 Pulitzer Prize for Poetry with her book Native Guard. Lesser-known poets such as Thylias Moss also have been praised for their innovative work. Notable black playwrights include Ntozake Shange, who wrote For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide When the Rainbow Is Enuf (1976), Ed Bullins, Suzan-Lori Parks, and the prolific August Wilson, who won two Pulitzer Prizes for his plays. More recently, Edward P. Jones won the 2004 Pulitzer Prize for Fiction for The Known World (2003), his novel about a black slaveholder in the antebellum South.

Younger African American novelists include David Anthony Durham, Karen E. Quinones Miller, Tayari Jones, Kalisha Buckhanon, Mat Johnson, ZZ Packer and Colson Whitehead, to name a few. African American literature has also crossed over to genre fiction. A pioneer in this area is Chester Himes, who in the 1950s and '60s wrote a series of pulp fiction detective novels featuring "Coffin" Ed Johnson and "Gravedigger" Jones, two New York City police detectives. Himes paved the way for the later crime novels of Walter Mosley and Hugh Holton.

African Americans are also represented in the genres of science fiction, fantasy and horror, with Samuel R. Delany, Octavia E. Butler, Steven Barnes, Tananarive Due, Robert Fleming, Brandon Massey, Charles R. Saunders, John Ridley, John M. Faucette, Sheree Thomas and Nalo Hopkinson being just a few of the well-known authors. Many of these novelist take influence from writings like Toni Morrison's Beloved and Harriet Jacobs, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl that allude to the social injustices African Americans have faced in American history.[59] Incorporating these themes with characteristics of the Gothic, science fiction, and dystopian genres, stories like Octavia E. Butler's have begun to gain literary honor and critique. Butler's work, Fledgling illustrates a unique vampire mythology, tackling notions of racial superiority and gender roles. Authors like Brandon Massey strategically places some of his stories in Gothic southern settings that fuel the fear of his plots. Much like Morrison's haunted house, placing mystery and suspense in antebellum style houses is strategic to their craft.

As a matter of fact, the literature industry in the United States including publishing and translation has always been described as predominantly white. Definitely, there were some principal works written by black authors such as Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass (1845) by Frederick Douglass, Twelve Years a Slave (1853) by Solomon Northrup, and The Souls of Black Folk (1903) by W. E. B. Du Bois that were translated into many languages.

However, for each of those literary works, there were dozens of novels, short stories and poems written by white authors that gained the same or even greater recognition. What is more, there were many literary pieces written by non-English speaking white authors that were translated into the English language. These works are widely known across the United States now. It is proof that there is a considerable gap in the literature that is available for US readers. This issue contributes to the problem of racial discrimination fostering the ignorant awareness of the white community.[60]

Finally, African American literature has gained added attention through the work of talk-show host Oprah Winfrey, who repeatedly has leveraged her fame to promote literature through the medium of her Oprah's Book Club. At times, she has brought African American writers a far broader audience than they otherwise might have received.

Hip-hop literature has become popular recently in the African American community.[61]

In the 21st century, the Internet has facilitated publication of African American literature. Founded in 1996 by Memphis Vaughn, TimBookTu has been a pioneer offering an online audience poetry, fiction, essays and other forms of the written word.[62]

Critiques

[edit]While African American literature is well accepted in the United States, there are numerous views on its significance, traditions, and theories. To the genre's supporters, African American literature arose out of the experience of Blacks in the United States, especially with regards to historic racism and discrimination, and is an attempt to refute the dominant culture's literature and power. In addition, supporters see the literature existing both within and outside American literature and as helping to revitalize the country's writing. To critics [who?], African American literature is part of a Balkanization of American literature. In addition, there are some within the African American community who do not like how their own literature sometimes showcases Black people.

Refuting the dominant literary culture

[edit]Throughout American history, African Americans have been discriminated against and subject to racist attitudes. This experience inspired some Black writers, at least during the early years of African American literature, to prove they were the equals of European-American authors. As Henry Louis Gates, Jr, has said, "it is fair to describe the subtext of the history of black letters as this urge to refute the claim that because blacks had no written traditions they were bearers of an inferior culture."[63]

By refuting the claims of the dominant culture, African American writers were also attempting to subvert the literary and power traditions of the United States. Some scholars assert that writing has traditionally been seen as "something defined by the dominant culture as a white male activity."[63] This means that, in American society, literary acceptance has traditionally been intimately tied in with the very power dynamics which perpetrated such evils as racial discrimination. By borrowing from and incorporating the non-written oral traditions and folk life of the African diaspora, African American literature broke "the mystique of connection between literary authority and patriarchal power."[64] In producing their own literature, African Americans were able to establish their own literary traditions devoid of the white intellectual filter. In 1922, W. E. B. Du Bois wrote that "the great mission of the Negro to America and to the modern world" was to develop "Art and the appreciation of the Beautiful".[65]

Existing both inside and outside American literature

[edit]According to Joanne Gabbin, a professor, African American literature exists both inside and outside American literature. "Somehow African-American literature has been relegated to a different level, outside American literature, yet it is an integral part," she says.[66] She bases her theory in the experience of Black people in the United States. Even though African Americans have long claimed an American identity, during most of United States history they were not accepted as full citizens and were actively discriminated against. As a result, they were part of America while also outside it.

Similarly, African American literature is within the framework of a larger American literature, but it also is independent. As a result, new styles of storytelling and unique voices have been created in relative isolation. The benefit of this is that these new styles and voices can leave their isolation and help revitalize the larger literary world (McKay, 2004). This artistic pattern has held true with many aspects of African American culture over the last century, with jazz and hip hop being just two artistic examples that developed in isolation within the Black community before reaching a larger audience and eventually revitalizing American culture.

Since African American literature is already popular with mainstream audiences, its ability to develop new styles and voices—or to remain "authentic," in the words of some critics—may be a thing of the past.[17]

Balkanization of American literature

[edit]Some conservative academics and intellectuals argue that African American literature exists as a separate topic only because of the balkanization of literature over the last few decades, or as an extension of the culture wars into the field of literature.[67] According to these critics, literature is splitting into distinct and separate groupings because of the rise of identity politics in the United States and other parts of the world. These critics reject bringing identity politics into literature because this would mean that "only women could write about women for women, and only Blacks about Blacks for Blacks."[67]

People opposed to this group-based approach to writing say that it limits the ability of literature to explore the overall human condition. Critics also disagree with classifying writers on the basis of their race, as they believe this is limiting and artists can tackle any subject.

Proponents counter that the exploration of group and ethnic dynamics through writing deepens human understanding and previously, entire groups of people were ignored or neglected by American literature.[68] (Jay, 1997)

The general consensus view appears to be that American literature is not breaking apart because of new genres such as African-American literature. Instead, American literature is simply reflecting the increasing diversity of the United States and showing more signs of diversity than before in its history (Andrews, 1997; McKay, 2004).

African American criticism

[edit]Some of the criticism of African American literature over the years has come from within the community; some argue that black literature sometimes does not portray black people in a positive light and that it should.

W. E. B. Du Bois wrote in the NAACP's magazine The Crisis on this topic, saying in 1921: "We want everything that is said about us to tell of the best and highest and noblest in us. We insist that our Art and Propaganda be one." He added in 1926, "All Art is propaganda and ever must be, despite the wailing of the purists."[65] Du Bois and the editors of The Crisis consistently stated that literature was a tool in the struggle for African American political liberation.

Du Bois's belief in the propaganda value of art showed when he clashed in 1928 with the author Claude McKay over his best-selling novel Home to Harlem. Du Bois thought the novel's frank depictions of sexuality and the nightlife in Harlem appealed only to the "prurient demand[s]" of white readers and publishers looking for portrayals of Black "licentiousness". Du Bois said, "'Home to Harlem' ... for the most part nauseates me, and after the dirtier parts of its filth I feel distinctly like taking a bath."[69] Others made similar criticism of Wallace Thurman's novel The Blacker the Berry in 1929. Addressing prejudice between lighter-skinned and darker-skinned Blacks, the novel infuriated many African Americans, who did not like the public airing of their "dirty laundry".[70]

Many African American writers thought their literature should present the full truth about life and people. Langston Hughes articulated this view in his essay "The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain" (1926). He wrote that Black artists intended to express themselves freely no matter what the Black public or white public thought.

More recently, some critics accused Alice Walker of unfairly attacking black men in her novel The Color Purple (1982).[71] In his updated 1995 introduction to his novel Oxherding Tale, Charles Johnson criticized Walker's novel for its negative portrayal of African American men: "I leave it to readers to decide which book pushes harder at the boundaries of convention, and inhabits most confidently the space where fiction and philosophy meet." Walker responded in her essays The Same River Twice: Honoring the Difficult (1998).

Robert Hayden, the first African American Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress, critiqued the idea of African American literature by saying (paraphrasing the comment by the black composer Duke Ellington about jazz and music): "There is no such thing as Black literature. There's good literature and bad. And that's all."[72]

Kenneth Warren's What Was African American Literature?[73] argues that black American writing, as a literature, began with the institution of Jim Crow legislation and ended with desegregation. In order to substantiate this claim, he cites both the societal pressures to create a distinctly black American literature for uplift and the lack of a well formulated essential notion of literary blackness. For this scholar, the late 19th and early 20th centuries de jure racism crystallized the canon of African American literature as black writers conscripted literature as a means to counter notions of inferiority. During this period, "whether African American writers acquiesced in or kicked against the label, they knew what was at stake in accepting or contesting their identification as Negro writers."[74] He writes that "[a]bsent white suspicion of, or commitment to imposing, black inferiority, African American literature would not have existed as a literature".[75] Warren bases part of his argument on the distinction between "the mere existence of literary texts" and the formation of texts into a coherent body of literature.[73] For Warren, it is the coherence of responding to racist narratives in the struggle for civil rights that establishes the body of African American literature, and the scholar suggests that continuing to refer to the texts produced after the civil rights era as such is a symptom of nostalgia or a belief that the struggle for civil rights has not yet ended.[73]

In an alternative reading, Karla F. C. Holloway's Legal Fictions: Constituting Race, Composing Literature (Duke University Press, 2014) suggests a different composition for the tradition and argues its contemporary vitality.[76] Her thesis is that legally cognizable racial identities are sustained through constitutional or legislative act, and these nurture the "legal fiction" of African American identity. Legal Fictions argues that the social imagination of race is expressly constituted in law and is expressively represented through the imaginative composition of literary fictions. As long as US law specifies a black body as "discrete and insular," it confers a cognizable legal status onto that body. US fictions use that legal identity to construct narratives — from neo-slave narratives to contemporary novels such as Walter Mosley's The Man in My Basement – that take constitutional fictions of race and their frames (contracts, property, and evidence) to compose the narratives that cohere the tradition.

Criticism regarding African American literature in the spaces of education have influenced which stories can and should be taught in schools. Nina Mikkelsen's Insiders, Outsiders, and the Question of Authenticity: Who Shall Write for African American Children?[77] argues for the importance of authenticity when it comes to writing stories for young African-American audiences. Mikkelsen tracks the significance of having students exposed to diversity while also maintaining authentic narratives by incorporating stories that not only include characters of color but are also written by people of color. While her perspective is broad and marketed towards writers and readers themselves, incorporating her same themes and analysis to authentic narratives proves useful in a classroom setting. She challenges what previous 'diverse' narratives might have accomplished while also dissecting why they were demeaning to the culture of authentic storytelling itself. This article fits into the discourse on having diverse literature for students to see themselves in the classroom and the importance of choosing texts who's storytelling resonates with their own culture. Mikkelsen writes, "The idea of multicultural literature (that in which the idea of different world views or cultural references are built into the texture of the book itself-its focus, its emphasis, its subject matter) is a challenging one for readers who are not insiders of the culture being depicted."[77] She believes providing students with content that portrays authentic and genuine reflections of multi-cultural experiences, allows for better engagement and connection in the classroom for those who resonate with these cultures.

African American women's literature

[edit]African American women's literature is literature created by American women of African descent. African American women like Phillis Wheatley Peters and Lucy Terry in the 18th century are often cited as the founders of the African American literary tradition. Social issues discussed in the works of African American women include racism, sexism, classism and social equality. African American women's literature can be dated as far back as 1845 with Frances Ellen Watkins Harper's poem, Forest Leaves.[78]

Anna Julia Cooper

[edit]Anna Julia Cooper in her book from 1892 titled A Voice from the South: By a Black Woman of the South argued for greater and more widespread attainment of higher education for African Americans, especially women. Her work attempts to cultivate a sense of educational rigor in African American female intellectuals and the black community in the US would benefit from as a whole.[79] This is to counter the overly aggressive and male-dominated academic writings in higher education and balance them with more female voices, hence Cooper is widely recognized as the "mother of Black feminism".[80] Furthermore, Cooper did not just see higher education as a way to improve the socioeconomic situation of African American communities, but also as a foundation for the continuous learning and a community based approach to upliftment that would cause the "universal betterment" of people and humanity as a whole.[81] Cooper advocated for the democratization of both public and private higher education which has been seen as "bastions of white, male elitism" and a "focus on reproducing English culture and cementing Christian doctrine", as the changing nature of American culture that now grapples with centuries of relegating women and racial minorities to the lowest rungs of society.[82]

Ann Folwell Stanford

[edit]In the article "Mechanisms of Disease: African-American Women Writers, Social Pathologies, and the Limits of Medicine" (1994), Ann Folwell Stanford argues that novels by African American women writers Toni Cade Bambara, Paule Marshall, and Gloria Naylor offer a feminist critique of the biomedical model of health that reveals the important role of the social (racist, classist, sexist) contexts in which bodies function.[83]

Barbara Christian

[edit]In 1988, Barbara Christian discusses the issue of "minority disclosure".[84]

Frances Ellen Watkins Harper

[edit]Frances Ellen Watkins Harper wrote many poems throughout her career including, Forest Leaves (1845), Sketches of Southern Life (1891), and Lola Leroy or Shadows Uplifted (1892).[78] Many of her poems were written about alcoholism and its effect on the black community.[85]

Alice Walker

[edit]Alice Walker is known for her contribution to African American Literature. One of her more famous novels is The Color Purple (1982) which received criticism and praise.[86]

See also

[edit]- African American Review

- Black sermonic tradition

- AALBC.com

- African American

- African American history

- Africanfuturism

- Afrofuturism

- American literature

- Baltimore Afro-American

- Callaloo (journal)

- Chicano literature

- Daughters of Africa

- Ebony

- Jet

- List of African American writers

- List of Black New York Times Best Selling Authors

- Mythology of Benjamin Banneker

- Negro Digest

- The Journal of African American History

- Southern Gothic

- Timeline of African American children's literature

- Urban fiction

Notes

[edit]- ^ Jerry W. Ward, Jr., "To Shatter Innocence: Teaching African American Poetry", in Teaching African American Literature, ed. M. Graham, Routledge, 1998, p. 146, ISBN 041591695X.

- ^ Peterson, Carla (1995). Doers of the Word: African-American Women Speakers and Writers in the North (1830–1880). New York: Oxford University Press. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-8135-2514-3.

- ^ Darryl Dickson-Carr, The Columbia Guide to Contemporary African American Fiction, New York: Columbia University Press, 2005, pp. 10-11, ISBN 0-231-12472-4.

- ^ a b Katherine Driscoll Coon, "A Rip in the Tent: Teaching African American Literature", in Teaching African American Literature, ed. M. Graham, Routledge, 1998, p. 32, ISBN 041591695X.

- ^ Valerie Sweeney Prince, Burnin' Down the House: Home in African American Literature, New York: Columbia University Press, 2005, ISBN 0-231-13440-1.

- ^ Drexler, Michael (2008). Beyond Douglass: New Perspectives on Early African-American Literature. Lewisburg: Bucknell University Press. p. 69. ISBN 9780838757116.

- ^ Dickson-Carr,The Columbia Guide, p. 73.

- ^ Radhika Mohanram and Gita Rajan, English Postcoloniality: Literatures from Around the World, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 1996, p. 135, ISBN 0313288542.

- ^ Ward, Jr., "To Shatter Innocence", p. 146.

- ^ Henry Louis Gates, Jr., The Signifying Monkey: A Theory of African American Literary Criticism, New York: Oxford, 1988, p. xix, ISBN 0195034635.

- ^ Henry Louis Gates Jr., "The Blackness of Blackness: A Critique of the Sign and the Signifying Monkey", in Julie Rivkin and Michael Ryan (eds), Literary Theory: An Anthology, 2nd edn, Wiley-Blackwell, 2004, p. 988.

- ^ Gates, "The Blackness of Blackness", in Literary Theory (2004), p. 992.

- ^ "Slave narratives". PBS.

- ^ "Brief History of African-American Literature. Part 1. Slave Narratives".

- ^ Richard S. Newman (2009). "Liberation Technology: Black Printed Protest in the Age of Franklin". Early American Studies. 8 (1): 173–198. doi:10.1353/eam.0.0033. ISSN 1559-0895.

- ^ Adams, Catherine; Pleck, Elizabeth (2010). Love of Freedom: Black Women in Colonial and Revolutionary New England. New York: Oxford University Press. Kindle Location 1289. ISBN 978-0-19-538909-8.

- ^ a b Cashmore, Ellis (April 25, 1997). "Profit and oppression: Black culture was long denied recognition. The danger now is that it is being turned into another commodity" [Review of Gates, Henry Louis, Jr; McKay, Nellie Y (eds.), The Norton Anthology of African American Literature, W W Norton]. New Statesman & Society. Vol. 10, no. 45. London, UK: Statesman and Nation Publishing Company, Ltd. pp. 52–53. ISSN 0954-2361. ProQuest 224404807 (accession number 03258059); EBSCOhost 9705133733; Factiva nsts000020011007dt4p000dd; Google Books New Statesman & Society.

• Cashmore, Ellis (April 25, 1997). "The Norton Anthology of African-American Literature". New Statesman. Vol. 126, no. 4331. London, UK: Statesman and Nation Publishing Company, Ltd. pp. 52–53. eISSN 1758-924X. ISSN 1364-7431. Gale A19997743; Google Books New Statesman. - ^ Gates, Henry Louis (1997). The Norton Anthology of African American Literature. New York: W.W. Norton. p. 214. ISBN 978-0393959086.

- ^ An address to the Negroes in the state of New-York Archived November 28, 2009, at the Wayback Machine, by Jupiter Hammon, servant of John Lloyd, Jun, Esq; of the manor of Queen's Village, Long-Island. 1778.

- ^ Victor Séjour, Philip Barnard (translator). "The Mulatto." In Nellie Y. McKay, Henry Louis Gates (eds), The Norton Anthology of African American Literature Second edition, Norton, 2004. ISBN 0-393-97778-1.

- ^ "William Wells Brown, 1814?-1884: Clotel; or, The President's Daughter: A Narrative of Slave Life in the United States. By William Wells Brown, A Fugitive Slave, Author of 'Three Years in Europe.' With a Sketch of the Author's Life" Archived October 28, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. Documenting the American South.

- ^ Mary Maillard. "'Faithfully Drawn from Real Life' Autobiographical Elements in Frank J. Webb's The Garies and Their Friends" Archived February 4, 2019, at the Wayback Machine, Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 137.3 (2013): 261–300.

- ^ O'Meally, Robert; Wilson, Harriet E.; Gates, Henry Louis (1984). "Slavery's Shadow". Callaloo (20): 157–158. doi:10.2307/2930697. JSTOR 2930697.

- ^ Ferguson, Moira (1998). Nine Black Women: An Anthology of Nineteenth-Century Writers from the United States, Canada, Bermuda and the Caribbean. New York: Routledge. p. 118. ISBN 978-0415919043.

- ^ Ferguson, Moira (1998). Nine Black Women. p. 119.

- ^ Stern, Julia (September 1995). "Excavating Genre in Our Nig". American Literature. 3. 67 (3): 439–466. doi:10.2307/2927939. JSTOR 2927939.

- ^ Gates, Henry Louis (2004). In Search of Hannah Crafts: Critical Essays on The Bondwoman's Narrative. New York: Basic Civitas. pp. 3–4. ISBN 978-0465027149.

- ^ Gates (2004). In Search of Hannah Crafts. p. xi.

- ^ Gates (2004). In Search of Hannah Crafts. pp. 6–7.

- ^ a b Arvind Tupere, Bharat (2020). Expression of Self Emancipation: A Study of Black Women's Autobiographies. North Carolina: Lulu Publication. pp. 34–35. ISBN 978-1-79488-064-1.

- ^ Yellin, Jean Fagan. "Written by Herself: Harriet Jacobs' Slave Narrative." American Literature, vol. 53, no. 3, 1981, pp. 479–486. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/2926234. Retrieved April 25, 2021.

- ^ "The Slave Route: Who was Frederick Douglass?". United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization. Archived from the original on November 8, 2018. Retrieved November 7, 2018.

- ^ McCrum, Robert (May 22, 2017). "The 100 best nonfiction books: No 68 – Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave by Frederick Douglass (1845)". The Guardian. Archived from the original on September 22, 2018. Retrieved September 21, 2018.

- ^ Andrews, William (1986). Sisters of the Spirit: Three Black Women's Autobiographies of the Nineteenth Century. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-0253352606.

- ^ Peterson, Carla. Doers of the Word. p. 5.

- ^ Peterson, Carla. Doers of the Word. p. 3.

- ^ Andrews, William (1986). Sisters of the Spirit: Three Black Women's Autobiographies of the Nineteenth Century. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. p. 2. ISBN 978-0253352606.

- ^ Foster, Frances Smith (1993). Written By Herself: Literary Production by African American Women, 1746–1892. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. p. 84. ISBN 978-0253324092.

- ^ a b Foster (1993). Written By Herself. p. 85.

- ^ Peterson, Carla. Doers of the Word. p. 57.

- ^ Peterson, Carla. Doers of the Word. pp. 66–67.

- ^ Ferguson, Moira, Nine Black Women, p. 148.

- ^ Peterson, Carla. Doers of the Word. p. 74.

- ^ Ferguson, Moira. Nine Black Women. p. 172.

- ^ Foster (1993). Written by Herself. p. 86.

- ^ Gates, Henry Louis (1997). The Norton Anthology of African American Literature. p. 245.

- ^ Watson, Carole M. (1985). Her Prologue: The Novels of Black American Women. Greenwood.

- ^ Eric Gardner, Jennie Carter: A Black Journalist of the Early West, University Press of Mississippi, January 1, 2007.

- ^ Du Bois, W.E.B. The Souls of Black Folk, Penguin Books, 1996, p. 10, ISBN 014018998X.

- ^ Gates (1997). The Norton Anthology of African American Literature. p. 491.

- ^ Gates (1997). The Norton Anthology of African American Literature. p. 365.

- ^ Dunbar, Paul Laurence (2000-07-14). "Paul Laurence Dunbar". Paul Laurence Dunbar. Archived from the original on 2018-12-02. Retrieved December 1, 2018.

- ^ "The Brownies' Book". The Tar Baby and the Tomahawk: Race and Ethnic Images in American Children's Literature, 1880-1939. Center for Digital Research in the Humanities at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln, in conjunction with the Center for the Humanities at Washington University in St. Louis. Archived from the original on October 11, 2015. Retrieved December 29, 2014.

- ^ Miller, Monica (December 17, 2012). "Archaeology of a Classic". News & Events. Barnard College. Retrieved June 14, 2014.

- ^ "9 Fascinating Facts About Zora Neale Hurston". Mental Floss. January 7, 2021.

- ^ David M. Katzman, "Black Migration Archived 2002-11-17 at the Wayback Machine," in The Reader's Companion to American History, Houghton Mifflin Co. Retrieved July 6, 2005. James Grossman, "Chicago and the 'Great Migration' Archived September 3, 2006, at the Wayback Machine", Illinois History Teacher 3, no. 2 (1996). Retrieved July 6, 2005.

- ^ Ronald Roach, "Powerful pages—unprecedented public impact of W.W. Norton and Co's Norton Anthology of African American Literature" Archived March 30, 2005, at the Wayback Machine, Black Issues in Higher Education, September 18, 1997. Retrieved July 6, 2005.

- ^ a b James A. Emanuel: A Register of His Papers in the Library of Congress Archived June 25, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, prepared by T. Michael Womack, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C., 2000. Retrieved May 6, 2006.

- ^ Weinauer, Ellen (November 23, 2017). "Race and the American Gothic". The Cambridge Companion to American Gothic. Cambridge University Press. pp. 85–98. doi:10.1017/9781316337998.007. ISBN 9781316337998. Retrieved November 30, 2021.

- ^ Carr, Michael (10 June 2020). "Why Translating Black Writers Matters". thewordpoint.com. Archived from the original on June 26, 2020. Retrieved June 26, 2020.

- ^ Bragg, Beauty, "Review of Writing the Future of Black America: Literature of the Hip-Hop Generation by Daniel Grassian", in MELUS, Vol. 35, No. 1, Transgressing the Borders of "America" (Spring 2010), pp. 184–186. Archived July 25, 2020, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "TimBookTu".

- ^ a b "The Other Ghost in Beloved: The Specter of the Scarlet Letter" by Jan Stryz from The New Romanticism: a collection of critical essays by Eberhard Alsen, p. 140, ISBN 0-8153-3547-4.

- ^ Quote from Marjorie Pryse in "The Other Ghost in Beloved: The Specter of the Scarlet Letter" by Jan Stryz, from The New Romanticism: a collection of critical essays by Eberhard Alsen, p. 140, ISBN 0-8153-3547-4.

- ^ a b Mason, "African-American Theory and Criticism" Archived May 15, 2005, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved July 6, 2005.

- ^ "Coup of the Century Archived February 22, 2005, at the Wayback Machine", James Madison University. Retrieved July 6, 2005.

- ^ a b Richard H. Brodhead, "On the Debate Over Multiculturalism" Archived March 17, 2005, at the Wayback Machine, On Common Ground , no. 7 (Fall 1996). Retrieved July 6, 2005.

- ^ Theodore O. Mason, Jr., "African-American Theory and Criticism" Archived May 15, 2005, at the Wayback Machine, Johns Hopkins Guide Literary Theory & Criticism; American Literature, College of Education, Cal State San Bernardino; Stephanie Y. Mitchem, "No longer nailed to the floor" Archived September 6, 2004, at the Wayback Machine, Cross Currents, Spring 2003;.

- ^ John Lowney, "Haiti and Black Transnationalism: Remapping the Migrant Geography of Home to Harlem Archived July 16, 2012, at the Wayback Machine," African American Review, Fall 2000. Retrieved July 6, 2005.

- ^ Frederick B. Hudson, "Black and Gay? A Painter Explores Historical Roots" Archived April 27, 2006, at the Wayback Machine, The Black World Today, April 25, 2005.

- ^ Michael E. Muellero, "Biography of Alice Walker" Archived July 20, 2005, at the Wayback Machine, Contemporary Black Biography 1; Jen Crispin, review of The Color Purple, by Alice Walker Archived February 7, 2005, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved July 6, 2005.

- ^ Biography of Robert Hayden Archived November 11, 2004, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved August 25, 2005.

- ^ a b c Kenneth Warren. What Was African American Literature? Archived 2013-05-16 at the Wayback Machine Harvard University Press, 2011.

- ^ Warren (2011), What Was African American Literature? Archived May 16, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, p. 8.

- ^ Warren (2011), What Was African American Literature? Archived May 16, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, p. 15.

- ^ Karla F. C. Holloway, Legal Fictions: Constituting Race, Composing Literature Archived August 30, 2020, at the Wayback Machine, Duke University Press, 2014. ISBN 978-0822355953.

- ^ a b Mikkelsen, Nina (1998). "Insiders, Outsiders, and the Question of Authenticity: Who Shall Write for African American Children?". African American Review. 32 (1): 33–49. doi:10.2307/3042266. JSTOR 3042266.

- ^ a b Poets, Academy of American. "Frances Ellen Watkins Harper". Poets.org. Retrieved 2023-11-21.

- ^ Guy-Sheftall, Beverly (October 7, 2021). "Black Feminist Studies: The Case of Anna Julia Cooper". African American Review. 43: 11–15. doi:10.1353/afa.0.0019. S2CID 161293124 – via Project Muse.

- ^ Bruner, Charlotte H. (1994). "Review: Daughters of Africa by Margaret Busby". World Literature Today. 68 (1): 189. doi:10.2307/40150048. ISSN 0196-3570. JSTOR 40150048.

- ^ Johnson, Karen (9 October 2021). ""In Service for the Common Good": Anna Julia Cooper and Adult Education". African American Review. 43: 45–56. doi:10.1353/afa.0.0023. S2CID 142854036 – via Project Muse.

- ^ Sule (2013). "Intellectual Activism: The Praxis of Dr. Anna Julia Cooper as a Blueprint for Equity-Based Pedagogy". Feminist Teacher. 23 (3): 211–229. doi:10.5406/femteacher.23.3.0211. JSTOR 10.5406/femteacher.23.3.0211. S2CID 145683841.

- ^ Stanford, Ann Folwell (1994). "Mechanisms of Disease: African-American Women Writers, Social Pathologies, and the Limits of Medicine". NWSA Journal. 6 (1): 28–47. ISSN 1040-0656. JSTOR 4316307.

- ^ Christian, Barbara (1988). "The Race for Theory". Feminist Studies. 14 (1): 67–79. doi:10.2307/3177999. ISSN 0046-3663. JSTOR 3177999.

- ^ "Frances Ellen Watkins Harper House (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Retrieved 2023-11-21.

- ^ Foundation, Poetry (2023-11-27). "Alice Walker". Poetry Foundation. Retrieved 2023-11-27.

References

[edit]- Andrews, W., F. Foster and T. Harris (eds).The Oxford Companion to African American Literature. Oxford, 1997.

- Brodhead, R. "An Anatomy of Multiculturalism". Yale Alumni Magazine, April 1994. Excerpted here.

- John Callahan, In the African-American Grain: Call and Response in Twentieth-Century Black Fiction, University of Illinois Press, reprinted 2001. ISBN 0-252-06982-X* Cashmore, E. "Review of the Norton Anthology of African American Literature" New Statesman, April 25, 1997.

- Dalrymple, T. "An Imaginary 'Scandal'", The New Criterion, May 2005.

- Davis, M., M. Graham, and S. Pineault-Burke (eds). Teaching African American Literature: Theory and Practice. Routledge, 1998.

- Gates, H. The Trials of Phillis Wheatley: America's First Black Poet and Her Encounters With the Founding Fathers, Basic Civitas Books, 2003

- Gilyard, K., and A. Wardi. African American Literature. Penguin, 2004.

- Greenberg, P. "I hate that (The rise of identity journalism)". Jewish World Review, June 15, 2005.

- Groden, M., and M. Krieswirth (eds). "African-American Theory and Criticism Archived 2005-05-15 at the Wayback Machine" from the Johns Hopkins Guide to Literary Theory and Criticism.

- Grossman, J. "Historical Research and Narrative of Chicago and the Great Migration".

- Hamilton, K. "Writers' Retreat: Despite the proliferation of Black authors and titles in today's marketplace, many look to literary journals to carry on the torch for the written word". Black Issues in Higher Education, November 6, 2003.

- Jay, G. American Literature and the Culture Wars. Cornell University Press, 1997. Excerpted here.

- Lowney, J. "Haiti and Black Transnationalism: Remapping the Migrant Geography of Home to Harlem", African American Review, Fall, 2000.

- McKay, N., and H. Gates (eds). The Norton Anthology of African American Literature, Second Edition. W. W. Norton & Company, 2004.

- Mitchem, S. "No Longer Nailed to the Floor". Cross Currents, Spring 2003.

- Nishikawa, K. "African American Critical Theory". Emmanuel S. Nelson (ed.), The Greenwood Encyclopedia of Multiethnic American Literature. 5 vols. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2005. 36–41.

- Nishikawa, K. "Crime and Mystery Fiction". Hans Ostrom and J. David Macey, Jr (eds), The Greenwood Encyclopedia of African American Literature. 5 vols. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2005. 360–67.

- Roach, R. "Powerful pages: Unprecedented Public Impact of W.W. Norton and Co's Norton Anthology of African American Literature". Black Issues in Higher Education, September 18, 1997.

- Scott, Daniel M. III (Fall–Winter 2004). "Harlem Shadows: Re-evaluating Wallace Thurman's The Blacker the Berry". MELUS: Multi-Ethnic Literature of the United States. 29 (3–4). Oxford University Press on behalf of The Society for the Study of the Multi-Ethnic Literature of the United States at University of Connecticut: 323–339. doi:10.2307/4141858. eISSN 1946-3170. ISSN 0163-755X. JSTOR 4141858. ProQuest 203668407. EBSCOhost 2004534308 (Update Code 20041, MLA Record Number 95366). Gale A128169772.

- Warren, K. W. What Was African American Literature? Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2011.

Further reading

[edit]- Dorson, Richard M., editor

- "Negro Folktales in Michigan", Harvard University Press, 1956.

- "Negro Tales from Pine Bluff, Arkansas, and Calvin, Michigan", 1958. ISBN 0-527-24650-6 ISBN 978-0-527-24650-1

- "American Negro Folktales", 1967.

- Gates, Henry Louis (1997). The Norton Anthology of African American Literature. New York: W.W. Norton. ISBN 978-0393959086.