Binky Brown Meets the Holy Virgin Mary

| Binky Brown Meets the Holy Virgin Mary | |

|---|---|

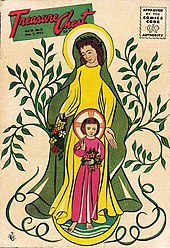

Original comic-book cover Last Gasp, 1972 | |

| Creator | Justin Green |

| Date | March 1972 |

| Page count | 44 pages |

| Publisher | Last Gasp Eco Funnies |

Binky Brown Meets the Holy Virgin Mary is an autobiographical comic by American cartoonist Justin Green, published in 1972. Green takes the persona of Binky Brown to tell of the "compulsive neurosis" with which he struggled in his youth and which he blamed on his strict Roman Catholic upbringing. Green was later diagnosed with obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) and came to see his problems in that light.

In the story, sinful thoughts that he cannot control torment Binky Brown; to his alarm, phallic objects become literal penises and project what he calls "pecker rays" at religious objects such as churches and statues of the Virgin Mary. He develops an internal set of rules to obey and punishments for breaking them. The torment does not subside, and he comes to reject the Catholic Church in defiance as the source of it. The work combines a wide variety of visual and narrative techniques in a style that echoes the torment of its protagonist.

Binky Brown had an immediate influence on contemporaries in underground comix: such cartoonists as Aline Kominsky, Robert Crumb, and Art Spiegelman soon turned to producing similarly confessional works. Binky Brown has gained a reputation as the first major work of autobiography in English-language comics, and many aspects of its approach have become widespread in underground and alternative comics.

Background

[edit]Justin Green (1945–2022) was born to a Jewish father and Catholic mother and raised Catholic.[1] As a child he at first attended a Catholic parochial school, and later transferred to a school where most students were Jews.[2] He rejected the Catholic faith in 1958 as he believed it caused him "compulsive neurosis"[3] that decades later was diagnosed as obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD).[4]

Green was studying painting at the Rhode Island School of Design when in 1967 he discovered the work of Robert Crumb and turned to cartooning, attracted to what he called Crumb's "harsh drawing stuffed into crookedly-drawn panels".[5] He experimented with his artwork to find what he called an "inherent and automatic style as a conduit for the chimerical forms in [his] own psyche".[6] He dropped out of an MFA program at Syracuse University[7] when in 1968 he felt a "call to arms"[5] to move to San Francisco, where the nascent underground comix scene was blossoming amid the counterculture there.[5] That year Green introduced a religion-obsessed character in the strip "Confessions of a Mad School Boy", published in a periodical in Providence, Rhode Island, in 1968. He named the character Binky Brown in "Binky Brown Makes up His Own Puberty Rites", published in the 17th issue of the underground comic book Yellow Dog in 1969. "The Agony of Binky Brown" followed in the first issue of Laugh in the Dark, published by Last Gasp in 1971.[8]

At the time, comic books had a reputation in the US as low-brow children's entertainment, and the public often associated them with juvenile delinquency. Comics had little cultural capital and few American cartoonists had challenged the perception that the medium was inherently incapable of mature artistic expression.[9]

Synopsis

[edit]Green (the cartoonist) takes the persona of Binky Brown,[10] who opens the story writing a confession of the neurosis that has tortured him since puberty. In Binky's childhood, he knocks over a statue of the Virgin Mary and feels intense guilt over this affront to his mother and to God. Binky is raised a Catholic and undergoes the religious indoctrination of nuns[11] at a strict Catholic parochial school that commonly employs corporal punishment.[12] He forms an image of a vengeful God, which fills him with feelings of fear and guilt.[11]

Binky's intrusive thoughts bring him to believe that his body is trying to lead him to sin and eternal punishment. He develops an internal system of rules to cope with these thoughts and punishes himself for violations. He wards off thoughts and fantasies he could not control, and that gives him guilt by silently repeating the word "noyatin" to himself, a contraction of the repentant "not a sin".[12]

As he approaches adolescence and becomes aware of his sexuality, he begins to see common objects as phalluses—phalluses that project unholy rays. These objects include Binky's fingers, toes, and his own penis, and he obsessively tries to deflect their "pecker rays" from reaching holy items such as churches or statues of Mary. Binky finds his anguish all-consuming as he imagines the destruction he cannot avoid and spends hours praying to God for forgiveness. Eventually Binky comes to the conclusion that he has sinned so much through his thoughts that he is bound for hell no matter what, and decides to experiment with a variety of activities considered sinful, including beer, speed, self-harm, Hesse novels, and acid trips. The narrator tells us that bad acid trips were like "water off a duck's back" to Binky, since everyday routines were already potentially traumatic experiences. As an adult, as the effects of an acid trip are beginning to wear off, Binky encounters a statue of the Virgin Mary in his path. Expecting to be tormented by his neuroses, he tries to dissolve the tension by facetiously singing "Lady of Spain". Binky is shocked when he walks by the statue and no distressing thoughts occur. Emboldened by this, Binky confronts his faith and by smashing a set of miniature statues of the Virgin Mary, he declares himself free of his obsession with sexual purity. Noticing that one of the statues in the pile has survived unscathed, he puts it on his mantel and says to himself "Mother of God, eh? Guess I'll build up some new associations around you now... Let bygones be bygones!" [11]

Composition and publication

[edit]

Green spent about a year working on the 44-page Binky Brown Meets the Holy Virgin Mary. He took a few months making cards of what he called "factual incidents or neurotic habits"[13] to incorporate. During the seven months he drew the work Green received a monthly stipend of $150 from Ron Turner, the founder of underground comix publisher Last Gasp Eco-Funnies.[13] Last Gasp published the story as a one-shot comic book in 1972[10]—Green's first solo title.[14] It went through two print runs of 55,000 copies each[4] with a "Youngsters Prohibited" label on the cover.[3]

In 1990, Green had an essay published entitled "The Binky Brown Matter" in The Sun.[15] In the essay, he describes the OCD with which he was diagnosed years after completing Binky Brown.[4] Last Gasp reprinted the story in 1995 in The Binky Brown Sampler, a softcover anthology of Binky Brown strips with an introduction by Art Spiegelman[11] and an expanded version of "The Binky Brown Matter".[15]

Green sold the original artwork to the strip in the 1970s; McSweeney's staff contacted the owner of the artwork, Christine Valenza, to make fresh scans for a standalone reprinting in 2009,[11] overseen by McSweeney's editor Eli Horowitz. It had a print run of 5,000 copies and reprints the artwork at the full size of the originals; the page reproductions mimic the actual pages, including marks, smudges, and corrections.[16] In 2011, the publisher Stara published a French translation by Harry Morgan titled Binky Brown rencontre la Vierge Marie,[17] and La Cúpula published a Spanish translation by Francisco Pérez Navarro titled Binky Brown conoce a la virgen María.[18]

Editions

[edit]| Year | Title | Publisher | ISBN | Format |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1972 | Binky Brown Meets the Holy Virgin Mary | Last Gasp Eco Funnies | Comic book | |

| 1995 | The Binky Brown Sampler | Last Gasp | 978-0-86719-332-9 | Softcover collection |

| 2009 | Binky Brown Meets the Holy Virgin Mary | McSweeney's | 978-1-934-78155-5 | Deluxe hardcover |

Style and analysis

[edit]

The story takes the form of a guilt-ridden confession.[19] In the opening, the adult Binky hangs over a sickle, bound from head to toe and listening to Ave Maria as he draws with a pen in his mouth.[20] He declares his intention: "to purge myself of the compulsive neurosis which I have served since I officially left Catholicism on Halloween, 1958".[3] He justifies the work to communicate with the "many others [who] are slaves to their neuroses" and who, despite believing themselves isolated, number so many that they "would entwine the globe many times over in a vast chain of common suffering".[20]

Though Green built Binky Brown on an autobiographical base he fabricated many scenes—such as one in which Binky is bullied by two third-graders—"to suggest or convey a whole generalized idea about some subjective feeling, such as order or fear or guilt".[13] To critic Charles Hatfield Binky Brown displays a "radical subjectivity"[21] that calls into question the notion of objectivity in autobiography.[21] The presentation is insistently subjective and non-literal in its visuals.[22]

Despite the heavy tone, humor is prominent.[23] The work is conscious of its own creation—Green's drawing of it frames the narrative proper and there are constant reminders of it throughout.[3] Green patterned the opening after those featuring the Crypt-Keeper in EC Comics' Tales from the Crypt series from the 1950s. Green used the adult Binky as the narrator of the captions and as a way to tie together the past and present timeframes.[6] There is a disconnect in that the narrator refers to his younger self as "he".[22] Other references to comics include a Sinstopper's Guidebook, which alludes to Dick Tracy's Crimestopper's Textbook[21] and a cartoon by Robert Crumb in the background.[3]

Green employs numerous Catholic symbols, such as a word balloon adorned with symbols of Christ's martyrdom to represent the depth of Binky's desperation. Catholic works such as a catechism and Treasure Chest parochial comics appear throughout the work.[3]

Despite strict censorship in other media in the US, explicit sexuality was common in underground comix. Binky Brown was the first work of autobiographical comics to depict explicit sexuality: penises appear throughout, and Binky masturbates in one scene.[24] The central symbol of the penis recurs sometimes subtly as in the images of pencils used to craft the work,[3] and more often explicitly, as every phallic-like object Green sees becomes a literal "pecker ray"-projecting penis in Binky's mind.[13]

Art Spiegelman described the artwork as "quirky and ungainly".[25] Though it appears awkward, Green put considerable effort into elements such as graphical perspective, and draws attention to his craft by depicting himself drawing and by placing the drawing manuals Perspective and Fun with a Pencil in the backgrounds. In contrast to the mundane tales of Harvey Pekar, another prominent early practitioner of autobiographical comics, Green makes wide use of visual metaphors.[3] In Binky Brown symbols become literal, as when Binky imagines himself becoming a snowball hurtling into Hell or as a fish chased by a police officer who wears a crucifix.[2] The work displays a wide array of visual techniques: diagrammatic arrows; mock-scholarly documentation; a great variety in panel size, composition, and layout; and a range of contrasting mechanical and organic rendering techniques, such as screentone alongside dense hand-drawn hatching.[21] The symbolic and technical collide where the Virgin Mary becomes the vanishing point of Binky's converging "pecker rays".[3]

Critic Joseph Witek sees the shifting between different modes of traditional comics representation at times presents a literalist view through "windowlike panels",[22] and at others "representational, symbolic, allegorical, associative, and allusive", an approach analogous to "Binky Brown's massively and chaotically overdetermined subjectivity".[22] Witek finds roots for the fractured psychological landscape of Binky Brown in the comics of earlier eras: the unrestrained psyches in the dreams of Winsor McCay's Dream of the Rarebit Fiend, the irrational, shifting landscapes of George Herriman's Krazy Kat, and Superman's obsessively contrarian nemesis Bizarro.[26]

In Binky Brown Green blames the Catholic Church for his psychological troubles; years later, he was diagnosed with OCD, and came to see these episodes in that light rather than as the fault of the Church.[11] He nevertheless continued to blame the Church for contributing to his anxieties and maintained that religion has a magnifying influence on the condition. He said the abandoning of both religion and recreational drugs made it easier to cope with his condition.[6] In 1990 a Catholic priest raised concerns that Binky Brown may be harmful to minors; Green countered that he believed it was the Church that was harming minors.[12] Green likened his OCD to a "split vision" which made him "both the slave to the compulsion and the detached observer".[9]

Literary scholar Hillary Chute sees the work as addressing feminist concerns of "embodiment and representation"[27] as it "delves into and forcefully pictures non-normative sexuality".[27] Chute affirms that despite its brevity Binky Brown merits the label "graphic novel" as "the quality of work, its approach, parameters, and sensibility"[5] mark a "seriousness of purpose".[5]

Reception and legacy

[edit]Green recounted "a strong energy" that Binky Brown drew from his readership, the first significant response he got from his work.[28] The story has had a wide influence on underground and alternative comics,[10] where its self-mocking[21] and confessional approach has inspired numerous cartoonists to expose intimate and embarrassing details of their lives.[29] Under the influence of Binky Brown, in 1972 Aline Kominsky published her first strip, the autobiographical "Goldie: A Neurotic Woman"[30] in Wimmen's Comix #1.[28] Other contemporary underground cartoonists were soon to incorporate confessional autobiography into their work.[31] Robert Crumb followed the same year with "The Confessions of R. Crumb" and continued with numerous other such strips.[13] Art Spiegelman, who had seen Binky Brown in mid-creation in 1971,[32] went as far as to state that "without Binky Brown there would be no Maus"—Spiegelman's most prominent work.[33] The same year as Binky Brown's publication, Green asked Spiegelman to contribute a three-page strip to the first issue of Funny Aminals, which Green edited and was published by Apex Novelties. Spiegelman delivered the three-page "Maus" in which Nazi cats persecute Jewish mice, inspired by his father's experiences in the Auschwitz concentration camp; years later he revisited the theme in the graphic novel of the same name.[34] Comics critic Jared Gardner asserts that, while underground comix was associated with countercultural iconoclasm, the movement's most enduring legacy was to be autobiography.[35]

Binky Brown went out of print for two decades after selling its initial print runs, during which time enthusiasts traded copies or photocopies.[25] Green made his living painting signs, and contributed occasional cartoon strips to various publications.[25] Green used the Binky Brown persona over the years in short strips and prose pieces that appeared in underground periodicals such as Arcade and Weirdo.[36] "Sweet Void of Youth" in 1976 follows Binky from high school to age thirty-one, torn between cartooning and more respected forms of art.[14] Aside from occasional one-off strips, his more regular cartooning appeared in the ongoing strips The Sign Game, in Signs of the Times magazine, and Musical Legends in America, in Pulse![37] Such later work has attracted far less attention than Binky Brown.[38]

Though autobiographical elements had appeared earlier in the work of underground cartoonists such as Crumb, Spain, and Kim Deitch,[39] Binky Brown Meets the Holy Virgin Mary has gained credit as the first important work of autobiographical comics in English.[40] To Charles Hatfield Binky Brown is "the ur-example of confessional literature in comics";[41] for Paul Gravett Green was "the first neurotic visionary to unburden his uncensored psychological troubles";[42] Douglas Wolk declared Green and his work "ahead of the memoirist curve";[43] Art Spiegelman declared: "What the Brontë sisters did for Gothic romance, what Tolkien did for sword-and-sorcery, Justin Green did for confessionary, autobiographical comix [sic]";[44] and Publishers Weekly called the work the "Rosetta Stone of autobiographical comics".[45]

Binky Brown Meets the Holy Virgin Mary has appealed mostly to comics fans and cartoonists, and has gained little recognition from mainstream audiences and arts critics. Spiegelman has speculated this neglect comes from the nature of the comics medium; in contrast to explicit works such as Philip Roth's Portnoy's Complaint, the penises in Green's work are visual.[25]

According to underground comix historian Patrick Rosenkranz, Green represents a break with past convention by being "the first to openly render his personal demons and emotional conflicts within the confines of a comic".[13] Green denied credit, calling confessional autobiography "a fait accompli, a low fruit ripe for the plucking",[13] examples of which abounded in literary works he had read by James Joyce, James T. Farrell, and Philip Roth. He has accepted credit for "anticipat[ing] the groundswell in literature about obsessive compulsive disorder by almost two decades",[13] for which he knew of no precedent.[13] Chute sees major themes of isolation and coping with OCD recurring in autobiographical works such as Howard Cruse's Stuck Rubber Baby (1995) and Alison Bechdel's Fun Home (2006).[4] Hatfield sees echoes of Green's unrestrained approach to dealing with a mental condition in Madison Clell's Cuckoo (2002)—about Clell's dissociative identity disorder—and in David B.'s Epileptic (2003).[21]

To cartoonist Jim Woodring, Green's autobiographical work "has never been surpassed".[46] Woodring's own autobiographical work in Jim draws from his dreams rather than his waking life.[46] British-American cartoonist Gabrielle Bell sympathized with Brown's approach, which she described as "talking about his feelings or his emotional state when he was illustrating it with striking images that were sort of absurd or a weird juxtaposition".[47] Green's influence extended overseas to cartoonists such as the Dutch Peter Pontiac, who drew inspiration from Binky Brown and Maus to produce Kraut (2000), about his father who collaborated with the Nazis during World War II.[46]

The story ranked No. 9 on The Comics Journal's list of the best hundred English-language comics of the 20th century,[48] and featured as the cover artwork for the autobiographical comics issue of the journal Biography (Vol. 31, No. 1).[31] Artwork to Binky Brown appeared in an exhibition of Green's work at Shake It Records in Cincinnati in 2009.[4]

- Autobiographical cartoonists inspired by Binky Brown Meets the Holy Virgin Mary

-

Robert Crumb took to putting himself on display shortly after reading Binky Brown.

-

Art Spiegelman stated there would have been no Maus without Binky Brown.

-

Jim Woodring stated Green's autobiographical work "has never been surpassed";[46] his own autobiographical work depicts his dreams.

References

[edit]- ^ Green 2010, p. 56.

- ^ a b Hatfield 2005, p. 135.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Hatfield 2005, p. 134.

- ^ a b c d e Green 2010, p. 58.

- ^ a b c d e Chute 2010, p. 17.

- ^ a b c Manning 2010.

- ^ Levin 1998, p. 101.

- ^ Bosky 2012, p. 89.

- ^ a b Gardner 2008, p. 12.

- ^ a b c Booker 2014, p. 480.

- ^ a b c d e f Booker 2014, p. 481.

- ^ a b c Green 2010, p. 57.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Rosenkrantz 2011, p. 1.

- ^ a b Levin 1998, p. 102.

- ^ a b Levin 1998, p. 103.

- ^ Reid 2009.

- ^ Bi 2011; Norot 2011.

- ^ Jiménez 2011; Queipo 2011.

- ^ Spiegelman 1995, pp. 4–5.

- ^ a b Gardner 2008, p. 8.

- ^ a b c d e f Hatfield 2005, p. 138.

- ^ a b c d Witek 2011, p. 229.

- ^ Spiegelman 1995, pp. 4–5; Rosenkrantz 2011, p. 1.

- ^ Chute 2010, pp. 18–19.

- ^ a b c d Spiegelman 1995, p. 5.

- ^ Witek 2011, pp. 229–230.

- ^ a b Chute 2010, p. 19.

- ^ a b Gardner 2008, p. 13.

- ^ Hatfield 2005, p. 138; Spiegelman 1995, p. 4.

- ^ Chute 2010, p. 34.

- ^ a b Witek 2011, p. 227.

- ^ Gardner 2008, p. 17.

- ^ Spiegelman 1995, p. 4.

- ^ Witek 1989, p. 103.

- ^ Gardner 2008, pp. 6–7.

- ^ Levin 2005, p. 88.

- ^ Levin 1998, p. 104.

- ^ Levin 1998, p. 107.

- ^ Gardner 2008, pp. 7–8.

- ^ Witek 2011, p. 227; Dycus 2011, p. 111.

- ^ Hatfield 2005, p. 131.

- ^ Gravett 2005, p. 22.

- ^ Wolk 2008, p. 203.

- ^ Gravett 2005, p. 23.

- ^ Publishers Weekly staff 2011.

- ^ a b c d Rosenkrantz 2011, p. 3.

- ^ Rosenkrantz 2011, p. 5.

- ^ Spurgeon 1999.

Works cited

[edit]Books

[edit]- Booker, M. Keith, ed. (2014). "Binky Brown Meets the Holy Virgin Mary". Comics through Time: A History of Icons, Idols, and Ideas. ABC-CLIO. pp. 480–482. ISBN 978-0-313-39751-6.

- Bosky, Bernadette (2012). "Binky Brown Sampler". In Beaty, Bart; Weiner, Stephen (eds.). Critical Survey of Graphic Novels: Independents and Underground Classics. Salem Press. pp. 89–93. ISBN 978-1-58765-950-8.

- Chute, Hillary L. (2010). Graphic Women: Life Narrative and Contemporary Comics. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-15063-7.

- Dycus, D. J. (2011). Chris Ware's Jimmy Corrigan: Honing the Hybridity of the Graphic Novel. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4438-3554-1.

- Gravett, Paul (2005). Graphic Novels: Stories to Change Your Life. Aurum. ISBN 978-1-84513-068-8.

- Green, Diana (2010). "Binky Brown Meets the Holy Virgin Mary". In Booker, M. Keith (ed.). Encyclopedia of Comic Books and Graphic Novels. ABC-CLIO. pp. 56–58. ISBN 978-0-313-35747-3.

- Hatfield, Charles (2005). Alternative Comics: An Emerging Literature. University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 978-1-60473-587-1.

- Levin, Bob (2005). Outlaws, Rebels, Freethinkers and Pirates. Fantagraphics Books. ISBN 978-1-56097-631-8.

- Spiegelman, Art (1995). "Symptoms of Disorder/Signs of Genius: Introduction". Justin Green's Binky Brown Sampler. Last Gasp. pp. 4–6. ISBN 978-0-86719-332-9.

- Witek, Joseph (1989). Comic Books as History: The Narrative Art of Jack Jackson, Art Spiegelman, and Harvey Pekar. University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 978-0-87805-406-0.

- Witek, Joseph (2011). "Justin Green: Autobiography Meets the Comics". In Chaney, Michael A. (ed.). Graphic Subjects: Critical Essays on Autobiography and Graphic Novels. University of Wisconsin Press. pp. 227–230. ISBN 978-0-299-25103-1.

- Wolk, Douglas (2008). Reading Comics: How Graphic Novels Work and What They Mean. Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-7867-2157-3.

Journals and magazines

[edit]- Gardner, Jared (2008). "Autography's Biography, 1972–2007" (PDF). Biography. 31 (1). University of Hawaii Press: 1–26. doi:10.1353/bio.0.0003. S2CID 161222880 – via Project MUSE.

- Levin, Bob (April 1998). "Rice, Beans and Justin Greens". The Comics Journal (203). Fantagraphics Books: 101–107. ISSN 0194-7869.

- Spurgeon, Tom, ed. (February 1999). "The Top 100 English-Language Comics of the Century". The Comics Journal (210). Fantagraphics Books: 34–108. ISSN 0194-7869.

Web

[edit]- Bi, Jessie (July 2011). "Binky Brown rencontre la Vierge Marie de Justin Green" (in French). Archived from the original on 2014-03-13. Retrieved 2015-06-28.

- Jiménez, Jesús (2011-06-17). "'Binky Brown conoce a la Virgen María', una obra maestra del cómic Underground". RTVE (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 2011-06-25. Retrieved 2015-06-28.

- Manning, Shaun (2010-01-22). "Justin Green on "Binky Brown"". Comic Book Resources. Archived from the original on 2015-01-19. Retrieved 2011-04-18.

- Norot, Anne-Claire (2011-07-25). "BD: "Binky Brown", un classique novateur et iconoclaste". Les Inrockuptibles (in French). Archived from the original on 2015-06-28. Retrieved 2015-06-28.

- Publishers Weekly staff (December 2011). "Binky Brown Meets The Holy Virgin Mary". Publishers Weekly. Archived from the original on 2015-06-29. Retrieved 2015-06-29.

- Queipo, Alan (2011-07-12). "Justin Green: Binky Brown conoce a la Virgen María". Notodo. Archived from the original on 2015-06-29. Retrieved 2015-06-28.

- Reid, Calvin (December 1, 2009). "Sex, Lies and Religion: A New Edition of 'Binky Brown Meets the Holy Virgin Mary'". Publishers Weekly. Archived from the original on 2015-01-19. Retrieved 2015-01-19.

- Rosenkrantz, Patrick (2011-03-06). "The ABCs of Autobio Comix". The Comics Journal. Fantagraphics Books. Archived from the original on 2014-03-05. Retrieved 2011-04-17.

Further reading

[edit]- Burbey, Mark (January 1986). "Comics and Catholics: Mark Burbey Interviews Justin Green". The Comics Journal (104). Fantagraphics Books: 37–49. ISSN 0194-7869.