Economy of Germany

Frankfurt, the financial center of Germany | |

| Currency | Euro (EUR, €) |

|---|---|

| Calendar year | |

Trade organisations | EU, WTO, G-20, G7 and OECD |

Country group |

|

| Statistics | |

| Population | |

| GDP | |

| GDP rank | |

GDP growth | |

GDP per capita | |

GDP per capita rank | |

GDP by sector |

|

GDP by component |

|

| |

Population below poverty line | 21.3% at risk of poverty or social exclusion (AROPE 2023)[8] |

Labour force | |

Labour force by occupation |

|

| Unemployment | |

Average gross salary | €4,924 monthly (2023) |

| €3,118 monthly (2023) | |

Main industries | |

| External | |

| Exports | $1.62 trillion (2022)[14][3] |

Export goods | motor vehicles, machinery, chemicals, computer and electronic products, electrical equipment, pharmaceuticals, metals, transport equipment, foodstuffs, textiles, rubber and plastic products |

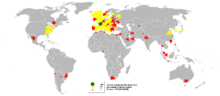

Main export partners |

|

| Imports | $1.17 trillion (2022)[15][3] |

Import goods | machinery, data processing equipment, vehicles, chemicals, oil and gas, metals, electric equipment, pharmaceuticals, foodstuffs, agricultural products |

Main import partners |

|

FDI stock | |

| $280 billion (2019)[3] | |

Gross external debt | $5.4 trillion (2022)[16] |

| Public finances | |

| Revenues | 46.1% of GDP (2023)[17] |

| Expenses | 48.6% of GDP (2023)[17] |

| Economic aid |

|

| $400 billion (2022)[23] | |

All values, unless otherwise stated, are in US dollars. | |

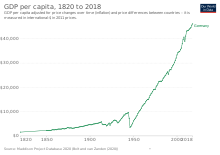

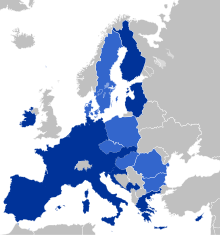

The economy of Germany is a highly developed social market economy.[24] It has the largest national economy in Europe, the third-largest by nominal GDP in the world, and fifth by GDP (PPP). Due to a volatile currency exchange rate, Germany's GDP as measured in dollars fluctuates sharply. In 2017, the country accounted for 28% of the Euro area economy according to the International Monetary Fund (IMF).[25] Germany is a founding member of the European Union and the eurozone.[26][27]

In 2016, Germany recorded the highest trade surplus in the world, worth $310 billion.[28] This economic result made it the biggest capital exporter globally.[29] Germany is one of the largest exporters globally with $1.81 trillion worth of goods and services exported in 2019.[30][31] The service sector contributes around 70% of the total GDP, industry 29.1%, and agriculture 0.9%. Exports accounted for 50.3% of national output.[32][33] The top 10 exports of Germany are vehicles, machinery, chemical goods, electronic products, electrical equipment, pharmaceuticals, transport equipment, basic metals, food products, and rubber and plastics.[34] The economy of Germany is the largest manufacturing economy in Europe, and it is less likely to be affected by a financial downturn.[35] Germany conducts applied research with practical industrial value and sees itself as a bridge between the latest university insights and industry-specific product and process improvements. It generates a great deal of knowledge in its own laboratories.[36] Among OECD members, Germany has a highly efficient and strong social security system, which comprises roughly 25% of GDP.[5][37][4]

Germany is rich in timber, lignite, potash, and salt. Some minor sources of natural gas are being exploited in the state of Lower Saxony. Until German reunification, the German Democratic Republic mined for uranium in the Ore Mountains (see also: SAG/SDAG Wismut). Energy in Germany is sourced predominantly by fossil fuels (30%), with wind power in second place, then gas, solar, biomass (wood and biofuels), and hydro.[38] Germany is the first major industrialised nation to commit to the renewable energy transition called Energiewende. Germany is the leading producer of wind turbines in the world.[39] Renewables produced 46% of electricity consumed in Germany (as of 2019).[40] Germany has been called "the world's first major renewable energy economy".[41][42] Germany has the world's second-largest gold reserve, with over 3,000 tonnes of gold.[43] Germany spends around 3.14% of GDP on advance research and development across various sectors of the economy.[44][45] It is also the world's second-largest high-technology exporter.[46]

More than 99 per cent of all German companies belong to the German "Mittelstand",[47] small and medium-sized enterprises, which are mostly family-owned. These companies represent 48% of the global market leaders in their segments, labelled hidden champions.[48] Of the world's 2000 largest publicly listed companies measured by revenue, the Fortune Global 2000, 53 are headquartered in Germany, as are 28 of Europe's 100 largest, with the top 10 being the following: Allianz, the world's largest insurance company and one of the largest financial services groups and asset managers, largest in Europe; Munich Re, also one of the largest insurance companies; Daimler, Volkswagen, and BMW, among the biggest car markers in the world;[49] Siemens, the world's biggest industrial machinery company; Deutsche Telekom, one of the world's largest telecommunication companies; Bayer, among the biggest biomedical companies; BASF, the world's 2nd biggest chemical producer; and SAP, Europe's biggest software company.[50] Other major companies include Lufthansa, Europe's largest airline, Deutsche Post, the largest logistics company worldwide,[51] Deutsche Bahn, the largest railway company in the world,[52][53][54] Bosch, the world's largest automotive supplier, Uniper, the world's largest energy company, and Aldi and Schwarz Gruppe, Europe's largest retailers.[55]

Germany is home to many financial centres and economically important cities, such as Berlin, Hamburg, Munich, Cologne, Frankfurt, and Stuttgart; 6 of the 10 biggest EU metropolitan areas by GDP are in Germany. 7 German banks are among the biggest in the world.

Germany is the world's top location for trade fairs;[56] around two thirds of the world's leading trade fairs take place in Germany.[57] Some of the largest international trade fairs and congresses are held in several German cities such as Hanover, Frankfurt, Cologne, Leipzig, and Düsseldorf.

History

[edit]

Age of Industrialisation

[edit]The Industrial Revolution in Germany got underway approximately a century later than in the United Kingdom, France, and Belgium, partly because Germany only became a unified country in 1871.[58]

-

Train factory of August Borsig in 1847

-

Many companies, such as steam-machine producer J. Kemna, modeled themselves on English industry.

-

BASF plant in Ludwigshafen, 1881

-

The invention of the automobile. Bertha Benz and Karl Benz in a Benz Viktoria, model 1894

-

The invention of the cruise ship. Albert Ballin's SS Auguste Viktoria in 1890

-

Railway construction as an expression of the Industrial Revolution (here the Bonn-Cölner railway around 1844)

The establishment of the Deutscher Zollverein (German Customs Union) in 1834 and the expansion of railway systems were the main drivers of Germany's industrial development and political union. From 1834, tariff barriers between increasing numbers of the Kleindeutschland German states were eliminated.[citation needed] In 1835 the first German railway linked the Franconian cities of Nuremberg and Fürth – it proved so successful that the decade of the 1840s saw "railway mania" in all the German states. Between 1845 and 1870, 8,000 kilometres (5,000 mi) of rail had been built and in 1850 Germany was building its own locomotives. Over time, other German states joined the customs union and started linking their railroads, which began to connect the corners of Germany. The growth of free trade and a rail system across Germany intensified economic development which opened up new markets for local products, created a pool of middle managers,[clarification needed] increased the demand for engineers, architects, and skilled machinists, and stimulated investments in coal and iron.[59]

Another factor that propelled German industry forward was the unification of the monetary system, made possible in part by political unification. The Deutsche Mark, a new monetary coinage system backed by gold, was introduced in 1871. However, this system did not fully come into use as silver coins retained their value until 1907.[citation needed]

The victory of Prussia and her allies over Napoleon III of France in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-1871 marked the end of French hegemony in Europe and resulted in the proclamation of the German Empire in 1871. The establishment of the empire inherently presented Europe with the reality of a new populous and industrialising polity possessing a considerable, and undeniably increasing, economic and diplomatic presence. The influence of French economic principles produced important institutional reforms in Germany, including the abolition of feudal restrictions on the sale of large landed estates, the reduction of the power of the guilds in the cities, and the introduction of a new, more efficient commercial law. Nonetheless, political decisions about the economy of the empire were still largely controlled by a coalition of "rye and iron", that is the Prussian Junker landowners of the east and the Ruhr heavy industry of the west.[60]

Regarding politics and society, between 1881 and 1889 Chancellor Otto von Bismarck promoted laws that provided social insurance and improved working conditions. He instituted the world's first welfare state. Germany was the first to introduce social insurance programmes including universal healthcare, compulsory education, sickness insurance, accident insurance, disability insurance, and a retirement pension. Moreover, the government's universal education policy bore fruit with Germany achieving[when?] the highest literacy rate in the world – 99% – education levels that provided the nation with more people good at handling numbers, more engineers, chemists, opticians, skilled workers for its factories, skilled managers, knowledgeable farmers, and skilled military personnel.[61]

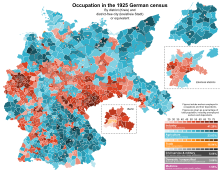

By 1900, Germany surpassed Britain in steel production and became the largest producer behind only the United States. The German economic miracle was also intensified by unprecedented population growth from 35 million in 1850 to 67 million in 1913. From 1895 to 1907, the number of workers engaged in machine building doubled from half a million to well over a million. Only 40 per cent of Germans lived in rural areas by 1910, a drop from 67% at the birth of the Empire. Industry accounted for 60 per cent of the gross national product in 1913.[62] The German chemical industry became the most advanced in the world, and by 1914 the country was producing half the world's electrical equipment.

The rapid advance to industrial maturity led to a drastic shift in Germany's economic situation – from a rural economy into a major exporter of finished goods. The ratio of the finished product to total exports jumped from 38% in 1872 to 63% in 1912. By 1913 Germany had come to dominate all the European markets. By 1914 Germany had become one of the biggest exporters in the world.[63]

Weimar Republic and Third Reich

[edit]

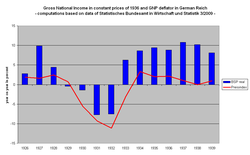

The Nazis rose to power while unemployment was very high,[64] but achieved full employment later thanks to massive public works programmes such as the Reichsbahn, Reichspost, and the Reichsautobahn projects.[65] In 1935 rearmament in contravention of the Treaty of Versailles added to the economy.[64][66]

The post-1931 financial crisis economic policies of expansionary fiscal policies (as Germany was off the gold standard) was advised by their non-Nazi Minister of Economics, Hjalmar Schacht,[64] who in 1933 became the president of the central bank. Schacht later resigned from the post in 1938 and was replaced by Hermann Göring.

The trading policies of the Third Reich aimed at self-sufficiency but with a lack of raw materials Germany would have to maintain trade links but on bilateral preferences, foreign exchange controls, import quotas, and export subsidies under what was called the "New Plan"(Neuer Plan) of 19 September 1934.[67] The "New Plan" was based on trade with less developed countries who would trade raw materials for German industrial goods saving currency.[68] Southern Europe was preferable to Western Europe and North America as there could be no trade blockades.[69] This policy became known as the Grosswirtschaftsraum ("greater economic area") policy.

Eventually, the Nazi party developed strong relationships with big business[70] and abolished trade unions in 1933 in order to form the Reich Labour Service (RAD), German Labour Front (DAF) to set working hours, Beauty of Labour (SDA) which set working conditions, and Strength through Joy (KDF) to ensure sports clubs for workers.[71]

West Germany

[edit]

Beginning with the replacement of the Reichsmark with the Deutsche Mark as legal tender, a lasting period of low inflation and rapid industrial growth was overseen by the government led by German Chancellor Konrad Adenauer and his minister of economics, Ludwig Erhard, raising West Germany from total wartime devastation to one of the most developed nations in modern Europe.

In 1953 it was decided that Germany was to repay $1.1 billion of the aid it had received. The last repayment was made in June 1971.

Apart from these factors, hard work and long hours at full capacity among the population in the 1950s, 1960s, and early 1970s and extra labour supplied by thousands of Gastarbeiter ("guest workers") provided a vital base for the economic upturn.

East Germany

[edit]By the early 1950s, the Soviet Union had seized reparations in the form of agricultural and industrial products and demanded further heavy reparation payments.[72] Silesia with the Upper Silesian Coal Basin, and Stettin, a prominent natural port, were lost to Poland.

Exports from West Germany exceeded $323 billion in 1988. In the same year, East Germany exported $30.7 billion worth of goods; 65% to other communist states.[73] East Germany had zero unemployment.[73]

Federal Republic

[edit]

The German economy practically stagnated in the beginning of the 2000s. The worst growth figures were achieved in 2002 (+1.4%), in 2003 (+1.0%), and in 2005 (+1.4%).[74] Unemployment was also chronically high.[75] Due to these problems, together with Germany's aging population, the welfare system came under considerable strain. This led the government to push through a wide-ranging programme of belt-tightening reforms, Agenda 2010, including the labour market reforms known as Hartz I - IV.[75]

In the later part of the first decade of 2000, the world economy experienced high growth, from which Germany as a leading exporter also profited. Some credit the Hartz reforms with achieving high growth and declining unemployment but others contend that they resulted in a massive decrease in standards of living and that its effects are limited and temporary.[75]

The nominal GDP of Germany contracted in the second and third quarters of 2008, putting the country in a technical recession following a global and European recession cycle.[76] German industrial output dropped to 3.6% in September vis-à-vis August.[77][78] In January 2009 the German government under Angela Merkel approved a €50 billion ($70 billion) economic stimulus plan to protect several sectors from a downturn and a subsequent rise in unemployment rates.[79] Germany exited the recession in the second and third quarters of 2009, mostly due to rebounding manufacturing orders and exports - primarily from outside the eurozone - and relatively steady consumer demand.[75]

Germany is a founding member of the EU, the G8, and the G20, and was the world's largest exporter from 2003 to 2008. In 2011 it remained the third largest exporter[80] and third largest importer.[81] Most of the country's exports are in engineering, especially machinery, automobiles, chemical goods, and metals.[82] Germany is a leading producer of wind turbines and solar-power technology.[83] Annual trade fairs and congresses are held in cities throughout Germany.[84] 2011 was a record-breaking year for the German economy. German companies exported goods worth over €1 trillion ($1.3 trillion), the highest figure in history. The number of people in work has risen to 41.6 million, the highest recorded figure.[85]

Through 2012, Germany's economy continued to be stronger relative to local neighbouring nations.[86] In 2023, Germany experienced economic difficulties as a result of the closure of Russian natural gas resources due to international sanctions following the Russian invasion of Ukraine.[87] Germany imported 55% of its gas from Russia at the time when Russia started the invasion in 2022.[88] Amid a global energy crisis, Chancellor Olaf Scholz committed to weaken dependence on Russian energy imports by halting certification of Nord Stream 2, while also committing to his long-term predecessor Angela Merkel's policy of phasing out nuclear energy.[89][90][88]

As of December 2023, Germany is the third largest economy in nominal terms in the world after the United States and China, and the largest economy in Europe. It is the third largest export nation in the world.[91]

In April 2024, a report by the German Economic Institute revealed that despite attempts to expand into other markets, the German economy remains heavily reliant on China for various products and raw materials.[92]

Data

[edit]The following table shows the main economic indicators in 1980–2021 (with IMF staff estimates in 2022–2027). Inflation below 5% is in green.[93]

| Year | GDP

(in Bil. US$PPP) |

GDP per capita

(in US$ PPP) |

GDP

(in Bil. US$nominal) |

GDP per capita

(in US$ nominal) |

GDP growth

(real) |

Inflation rate

(in Per cent) |

Unemployment

(in Per cent) |

Government debt

(in % of GDP) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1980 | 855.3 | 11,130.4 | 853.7 | 11,109.7 | 3.4% | n/a | ||

| 1981 | n/a | |||||||

| 1982 | n/a | |||||||

| 1983 | n/a | |||||||

| 1984 | n/a | |||||||

| 1985 | n/a | |||||||

| 1986 | n/a | |||||||

| 1987 | n/a | |||||||

| 1988 | n/a | |||||||

| 1989 | n/a | |||||||

| 1990 | n/a | |||||||

| 1991 | 39.0% | |||||||

| 1992 | ||||||||

| 1993 | ||||||||

| 1994 | ||||||||

| 1995 | ||||||||

| 1996 | ||||||||

| 1997 | ||||||||

| 1998 | ||||||||

| 1999 | ||||||||

| 2000 | ||||||||

| 2001 | ||||||||

| 2002 | ||||||||

| 2003 | ||||||||

| 2004 | ||||||||

| 2005 | ||||||||

| 2006 | ||||||||

| 2007 | ||||||||

| 2008 | ||||||||

| 2009 | ||||||||

| 2010 | ||||||||

| 2011 | ||||||||

| 2012 | ||||||||

| 2013 | ||||||||

| 2014 | ||||||||

| 2015 | ||||||||

| 2016 | ||||||||

| 2017 | ||||||||

| 2018 | ||||||||

| 2019 | ||||||||

| 2020 | ||||||||

| 2021 | ||||||||

| 2022 | ||||||||

| 2023 | ||||||||

| 2024 | ||||||||

| 2025 | ||||||||

| 2026 | ||||||||

| 2027 |

Companies

[edit]Of the world's 500 largest stock-market-listed companies measured by revenue in 2010, the Fortune Global 500, 37 are headquartered in Germany. 40 Germany-based companies are included in the DAX, the most popular German stock market index. Well-known global brands are Mercedes-Benz, BMW, SAP, Siemens, Volkswagen, Adidas, Audi, Allianz, Porsche, Bayer, BASF, Bosch, and Nivea.[94]

Germany is recognised for its specialised small and medium enterprises, known as the Mittelstand model. SMEs account for more than 99 per cent of German companies.[95] Around 1,000 of these companies are global market leaders in their segment and are labelled hidden champions.[96]

From 1991 to 2010, 40,301 mergers and acquisitions with an involvement of German firms with a total known value of 2,422 bil. EUR have been announced.[97] The largest transactions[98] since 1991 are: the acquisition of Mannesmann by Vodafone for 204.8 bil. EUR in 1999, the merger of Daimler-Benz with Chrysler to form DaimlerChrysler in 1998 valued at 36.3 bil. EUR.

Berlin developed an international startup ecosystem and became a leading location for venture capital funded firms in the European Union.[99]

The sector with the highest number of companies registered in Germany is Services with 1,443,708 companies followed by Finance, Insurance, and Real Estate and Construction with 480,593 and 173,167 companies respectively.[100]

The list includes the largest German companies by revenue in 2011:

| Rank[101] | Name | Headquarters | Ticker | Revenue (Mil. €) |

Profit (Mil. €) |

Employees (World) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Volkswagen Group | Wolfsburg | VOWG | 159,000 | 15,800 | 502,000 |

| 2. | E.ON | Essen | EONGn | 113,000 | −1,900 | 79,000 |

| 3. | Daimler | Stuttgart | DAIGn | 107,000 | 6,000 | 271,000 |

| 4. | Siemens | Berlin, München | SIEGn | 74,000 | 6,300 | 360,000 |

| 5. | BASF | Ludwigshafen am Rhein | BASFn | 73,000 | 6,600 | 111,000 |

| 6. | BMW | München | BMWG | 69,000 | 4,900 | 100,000 |

| 7. | Metro | Düsseldorf | MEOG | 67,000 | 740 | 288,000 |

| 8. | Schwarz Gruppe | Neckarsulm | 63,000 | N/A | 315,000 | |

| 9. | Deutsche Telekom | Bonn | DTEGn | 59,000 | 670 | 235,000 |

| 10. | Deutsche Post | Bonn | DPWGn | 53,000 | 1,300 | 471,000 |

| — | Bosch | Gerlingen | 73,100 | 2,300 | 390,000 | |

| — | Uniper | Düsseldorf | UNSE01 | 67,300 | 13,000 | |

| — | Allianz | München | ALVG | 104,000 | 2,800 | 141,000 |

| — | Deutsche Bank | Frankfurt am Main | DBKGn | 4,300 | 101,000 |

Mergers and acquisitions

[edit]Since German reunification, there have been 52,258 mergers or acquisitions deals inbound or outbound in Germany. The most active year in terms of value was 1999 with a cumulated value of 48. bil. EUR, twice as much as the runner up which was 2006 with 24. bil. EUR (see graphic "M&A in Germany").

Here is a list of the top 10 deals (ranked by value) that include a German company. The Vodafone - Mannesmann deal is still the biggest deal in global history.[102]

| Rank | Date | Acquirer | Acquirer Nation | Target | Target Nation | Value (in bil. USD) |

| 1 | 14 Nov 1999 | Vodafone AirTouch PLC | United Kingdom | Mannesmann AG | Germany | 202.79 |

| 2 | 18 May 2016 | Bayer AG | Germany | Monsanto Co | United States | 56.60 |

| 3 | 6 May 1998 | Daimler-Benz AG | Germany | Chrysler Corp | United States | 40.47 |

| 4 | 16 Aug 2016 | Linde AG | Germany | Praxair Inc | United States | 35.16 |

| 5 | 21 Oct 1999 | Mannesmann AG | Germany | Orange PLC | United Kingdom | 32.59 |

| 6 | 24 Jul 2000 | Deutsche Telekom AG | Germany | VoiceStream Wireless Corp | United States | 29.40 |

| 7 | 17 May 1999 | Rhone-Poulenc SA | France | Hoechst AG | Germany | 21.92 |

| 8 | 23 Mar 2006 | Bayer AG | Germany | Schering AG | Germany | 21.40 |

| 9 | 01 Apr 2001 | Allianz AG | Germany | Dresdner Bank AG | Germany | 19.66 |

| 10 | 30 May 2005 | Unicredito Italiano SpA | Italy | Bayerische Hypo- und Vereins | Germany | 18.26 |

Economic region

[edit]

Germany as a federation is a polycentric country and does not have a single economic centre. The stock exchange is located in Frankfurt am Main, the largest Media company (Bertelsmann SE & Co. KGaA) is headquartered in Gütersloh; the largest car manufacturers are in Wolfsburg (Volkswagen), Stuttgart (Mercedes-Benz and Porsche), and Munich (Audi and BMW).[103]

Germany is an advocate of closer European economic and political integration. Its commercial policies are increasingly determined by agreements among European Union (EU) members and EU single market legislation. Germany introduced the common European currency, the euro on 1 January 1999. Its monetary policy is set by the European Central Bank in Frankfurt.

The southern states ("Bundesländer"), especially Bayern, Baden-Württemberg, and Hessen, are economically stronger than the northern states. One of Germany's traditionally strongest (and at the same time oldest) economic regions is the Ruhr area in the west, between Duisburg and Dortmund. 27 of the country's 100 largest companies are located there. In recent years, however, the area, whose economy is based on natural resources and heavy industry, has seen a substantial rise in unemployment (2010: 8.7%).[103]

The economy of Bayern and Baden-Württemberg, the states with the lowest number of unemployed people (2018: 2.7%, 3.1%), on the other hand, is based on high-value products. Important sectors are automobiles, electronics, aerospace, and biomedicine, among others. Baden-Württemberg is an industrial centre especially for the automobile and machine-building industry and the home of brands like Mercedes-Benz (Daimler), Porsche and Bosch.[103]

With the reunification on 3 October 1990, Germany began the major task of reconciling the economic systems of the two former republics. Interventionist economic planning ensured gradual development in eastern Germany up to the level of former West Germany, but the standard of living and annual income remains significantly higher in western German states.[104] The modernisation and integration of the eastern German economy continues to be a long-term process scheduled to last until the year 2019, with annual transfers from west to east amounting to roughly $80 billion. The overall unemployment rate has consistently fallen since 2005 and reached a 20-year low in 2012. The country in July 2014 began legislating to introduce a federally mandated minimum wage which would come into effect on 1 January 2015.[105][needs update]

On 25 May 2023, a declaration of a recession in the German economy was made. It was reported that Gross Domestic Product (GDP) had contracted by 0.3% between January and March. This contraction was largely due to increased prices which discouraged consumer spending. The statistics office in Germany reported that household spending had dropped by 1.2% in the first quarter of the year.[106]

German states

[edit]| States | Rank | GRP (in billions EUR€) |

Share of GDP (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| — | 3,867.050 | 100 | |

| 1 | 793.790 | 20.5 | |

| 2 | 716.784 | 18.5 | |

| 3 | 572.837 | 14.8 | |

| 4 | 339.414 | 8.8 | |

| 5 | 323.352 | 8.4 | |

| 6 | 179.379 | 4.6 | |

| 7 | 171.699 | 4.4 | |

| 8 | 146.511 | 3.8 | |

| 9 | 144.220 | 3.7 | |

| 10 | 112.755 | 2.9 | |

| 11 | 88.800 | 2.3 | |

| 13 | 75.436 | 2.0 | |

| 12 | 71.430 | 1.8 | |

| 14 | 53.440 | 1.4 | |

| 16 | 38.698 | 1.0 | |

| 15 | 38.505 | 1.0 |

Wealth

[edit]

The following top 10 list of German billionaires is based on an annual assessment of wealth and assets compiled and published by Forbes magazine on 1 March 2016.[107]

- $27.9 billion Albrecht family

- $20.3 billion Theo Albrecht Jr.

- $18.5 billion Susanne Klatten

- $18.1 billion Georg Schaeffler

- $16.4 billion Dieter Schwarz

- $15.6 billion Stefan Quandt

- $15.4 billion Michael Otto

- $11.7 billion Heinz Hermann Thiele

- $10 billion Klaus-Michael Kühne

- $9.5 billion Hasso Plattner

Wolfsburg is the city in Germany with the country's highest per capita GDP, at $128,000. The following top 10 list of German cities with the highest per capita GDP is based on a study by the Cologne Institute for Economic Research on 31 July 2013.[108]

- $128,000 Wolfsburg, Lower Saxony

- $114,281 Frankfurt am Main, Hesse

- $108,347 Schweinfurt, Bavaria

- $104,000 Ingolstadt, Bavaria

- $99,389 Regensburg, Bavaria

- $92,525 Düsseldorf, North Rhine-Westphalia

- $92,464 Ludwigshafen am Rhein, Rhineland-Palatinate

- $91,630 Erlangen, Bavaria

- $91,121 Stuttgart, Baden-Württemberg

- $88,692 Ulm, Baden-Württemberg

Sectors

[edit]

Germany has a social market economy characterised by a highly qualified labour force, a developed infrastructure, a large capital stock, a low level of corruption,[109] and a high level of innovation.[110] It has the largest national economy in Europe, the third largest by nominal GDP in the world, and ranked fifth by GDP (PPP) in 2023.[7]

The service sector contributes around 70% of the total GDP, industry 29.1%, and agriculture 0.9%.[111]

Primary

[edit]In 2010 agriculture, forestry, and mining accounted for only 0.9% of Germany's gross domestic product (GDP) and employed only 2.4% of the population,[82] down from 4% in 1991. Agriculture is extremely productive, and Germany can cover 90% of its nutritional needs with domestic production. Germany is the third-largest agricultural producer in the European Union after France and Italy. Germany's principal agricultural products are potatoes, wheat, barley, sugar beets, fruit, and cabbages.[112]

Despite the country's high level of industrialisation, almost one-third of its territory is covered by forest.[113] The forestry industry provides for about two-thirds of domestic consumption of wood and wood products, so Germany is a net importer of these items.

The German soil is relatively poor in raw materials. Only lignite (brown coal) and potash salt (Kalisalz) are available in significant quantities. However, the former GDR's Wismut mining company produced a total of 230,400 tonnes of uranium between 1947 and 1990 and made East Germany the fourth-largest producer of uranium ore worldwide (largest in USSR's sphere of control) at the time. Oil, natural gas, and other resources are, for the most part, imported from other countries.[114]

Potash salt is mined in the centre of the country (Niedersachsen, Sachsen-Anhalt, and Thüringen). The most important producer is K+S (formerly Kali und Salz AG).[114]

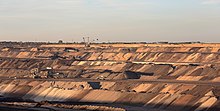

Germany's bituminous coal deposits were created more than 300 million years ago from swamps which extended from the present-day South England, over the Ruhr area to Poland. Lignite deposits developed similarly, but during a later period, about 66 million years ago. Because the wood is not yet completely transformed into coal, brown coal contains less energy than bituminous coal.[114]

Lignite is extracted in the extreme western and eastern parts of the country, mainly in Nordrhein-Westfalen, Sachsen, and Brandenburg. Considerable amounts are burned in coal plants near the mining areas, to produce electricity. Transporting lignite over far distances is not economically feasible, therefore the plants are located practically next to the extraction sites. Bituminous coal is mined in Nordrhein-Westfalen and Saarland. Most power plants burning bituminous coal operate on imported material, therefore the plants are located not only near to the mining sites, but throughout the country.[114]

In 2019, the country was the world's 3rd largest producer of selenium,[115] the world's 5th largest producer of potash,[116] the world's 5th largest producer of boron,[117] the world's 7th largest producer of lime,[118] the world's 13th largest producer of fluorspar,[119] the world's 14th largest producer of feldspar,[120] the world's 17th largest producer of graphite,[121] the world's 18th largest producer of sulfur,[122] in addition to being the 4th largest world producer of salt.[123]

Industry

[edit]

Industry and construction accounted for 30.7% of the gross domestic product in 2017 and employed 24.2% of the workforce.[3] Germany excels in the production of automobiles, machinery, electrical equipment, and chemicals. With the manufacture of 5.2 million vehicles in 2009, Germany was the world's fourth-largest producer and largest exporter of automobiles. German automotive companies enjoy an extremely strong position in the so-called premium segment, with a combined world market share of about 90%. All new automobiles sold in Germany must be zero-emission vehicles from 2035.[124]

Small- to medium-sized manufacturing firms (Mittelstand companies) which specialise in technologically advanced niche products and are often family-owned form a major part of the German economy.[125] It is estimated that about 1,500 German companies occupy a top three position in their respective market segment worldwide. In about two thirds of all industry sectors German companies belong to the top three competitors.[126]

Germany is the only country among the top five arms exporters that is not a permanent member of the United Nations Security Council.[127]

Services

[edit]In 2017 services constituted 68.6% of gross domestic product (GDP), and the sector employed 74.3% of the workforce.[82] The subcomponents of services are financial, renting, and business activities (30.5%); trade, hotels and restaurants, and transport (18%); and other service activities (21.7%).

Germany is the seventh most visited country in the world,[128][129] with a total of 407 million overnights during 2012.[130] This number includes 68.83 million nights by foreign visitors. In 2012, over 30.4 million international tourists arrived in Germany. Berlin has become the third most visited city destination in Europe.[131] Additionally, more than 30% of Germans spend their holiday in their own country, with the biggest share going to Mecklenburg-Vorpommern. Domestic and international travel and tourism combined directly contribute over EUR43.2 billion to German GDP. Including indirect and induced impacts, the industry contributes 4.5% of German GDP and supports 2 million jobs (4.8% of total employment).[132] The largest annual international trade fairs and congresses are held in several German cities such as Hannover, Frankfurt, and Berlin.[133]

Government finances

[edit]

The debt-to-GDP ratio of Germany had its peak in 2010 when it stood at 80.3% and decreased since then.[134] According to Eurostat, the government gross debt of Germany amounts to €2,152.0 billion or 71.9% of its GDP in 2015.[135] The federal government achieved a budget surplus of €12.1 billion ($13.1 billion) in 2015.[136] Germany's credit rating by credit rating agencies Standard & Poor's, Moody's, and Fitch Ratings stands at the highest possible rating AAA with a stable outlook in 2016.[137]

Germany's "debt clock" (Schuldenuhr) reversed for the first time in 20 years in January 2018. It is now currently increasing at 10,424.00 per second (October 2020).[138]

Economists generally see Germany's current account surplus as undesirable.[139]

Infrastructure

[edit]Energy

[edit]Germany is the world's fifth-largest consumer of energy, and two-thirds of its primary energy was imported in 2002. In the same year, Germany was Europe's largest consumer of electricity, totaling 512.9 terawatt-hours. Government policy promotes energy conservation and the development of renewable energy sources, such as solar, wind, biomass, hydroelectric, and geothermal energy. As a result of energy-saving measures, energy efficiency has been improving since the beginning of the 1970s. The government has set the goal of meeting half the country's energy demands from renewable sources by 2050. Renewable energy also plays an increasing role in the labour market: Almost 700,000 people are employed in the energy sector. About 50 per cent of them work with renewable energies.[140]

In 2000, the red-green coalition under Chancellor Schröder and the German nuclear power industry agreed to phase out all nuclear power plants by 2021.[141] The conservative coalition under Chancellor Merkel reversed this decision in January 2010, electing to keep plants open. The nuclear disaster of the Japanese nuclear plant Fukushima in March 2011 however, changed the political climate fundamentally: Older nuclear plants have been shut down. Germany is seeking to have wind, solar, biogas, and other renewable energy sources play a bigger role, as the country looks to completely phase out nuclear power by 2022 and coal-fired power plants by 2038.[142] Renewable energy yet still plays a more modest role in energy consumption, though German solar and wind power industries play a leading role worldwide. Germany has been called "the world's first major renewable energy economy".[41][42]

In 2009, Germany's total energy consumption (not just electricity) came from the following sources:[143] oil 34.6%, natural gas 21.7%, lignite 11.4%, bituminous coal 11.1%, nuclear power 11.0%, hydro and wind power 1.5%, others 9.0%.

In the first half of 2021, coal, natural gas, and nuclear energy comprised 56% of the total electricity fed into Germany's grid in the first half of 2021. Coal was the leader out of the conventional energy sources, comprising over 27% of Germany's electricity. Wind power's contribution to the electric grid was 22%.[142]

There are 3 major entry points for oil pipelines: in the northeast (the Druzhba pipeline, coming from Gdańsk), west (coming from Rotterdam) and southeast (coming from Nelahozeves). The oil pipelines of Germany do not constitute a proper network, and sometimes only connect two different locations. Major oil refineries are located in or near the following cities: Schwedt, Spergau, Vohburg, Burghausen, Karlsruhe, Cologne, Gelsenkirchen, Lingen, Wilhelmshaven, Hamburg, and Heide.[144]

Germany's network of natural gas pipelines, on the other hand, is dense and well-connected. Imported pipeline gas comes mostly from Russia, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom.

Transport

[edit]

With its central position in Europe, Germany is an important transportation hub. This is reflected in its dense and modern transportation networks. The extensive motorway (Autobahn) network ranks worldwide third largest in its total length and features a lack of blanket speed limits on the majority of routes.[145]

Germany has established a polycentric network of high-speed trains. The Intercity Express or ICE is the most advanced service category of the Deutsche Bahn and serves major German cities as well as destinations in neighbouring countries. The train maximum speed varies between 200 km/h and 320 km/h (125-200 mph). Connections are offered at either 30-minute, hourly, or two-hourly intervals.[146] German railways are heavily subsidised, receiving €17.0 billion in 2014.[147]

The largest German airports are Frankfurt Airport and Munich Airport, both are global hubs of Lufthansa. Other major airports are Berlin Brandenburg Airport, Düsseldorf, Hamburg, Hanover, Cologne/Bonn, and Stuttgart.

Banking system

[edit]Seven German banks are among the biggest in the world. As of 2019, Germany is the country in Europe with the highest number of credit institutions: between 1,600 and 1,800.[148] The types of institutions are in strong competition with each other: 390 Sparkassen and 8 public Landesbanken groups (1,200 billion euros of deposits), private commercial banks (DB, Commerzbank, and Unicredit-HypoVereinsbank, for 780 billion), cooperative credit banks (700 billion euros), savings banks, and Raiffeisen. The total of the system is worth 3,800 billion. 75% of retail customer deposits are managed by savings banks and cooperative credit banks.

According to Eurostat, in 2022 Germany also recorded the highest European rate of gross savings (19.98% of disposable income).[149]

Technology

[edit]

Germany's achievements in sciences have been significant, and research and development efforts form an integral part of the economy.[151]

Germany is also one of the leading countries in developing and using green technologies. Companies specialising in green technology have an estimated turnover of €200 billion. German expertise in engineering, science, and research is eminently respectable.

The lead markets of Germany's green technology industry are power generation, sustainable mobility, material efficiency, energy efficiency, waste management and recycling, sustainable water management.[152]

Regarding triadic patents, Germany is in third place after the U.S. and Japan. With more than 26,500 registrations for patents submitted to the European Patent Office, Germany is the leading European nation. Siemens, Bosch, and BASF, with almost 5,000 registrations for patents between them in 2008, are among the top 5 of more than 35,000 companies registering patents. Together with the U.S. and Japan, about patents for nano, bio, and new technologies Germany is one of the world's most active nations. With around one-third of triadic patents, Germany leads the way worldwide in the field of vehicle emission reduction.[153]

According to Winfried Kretschmann, who is premier of the region where Daimler is based, "China dominates the production of solar cells. Tesla is ahead in electric cars and Germany has lost the first round of digitalization to Google, Apple, and the like. Whether Germany has a future as an industrial economy will depend on whether we can manage the ecological and digital transformation of our economy".[154]

Challenges

[edit]

Despite economic prosperity, Germany's biggest threat to future economic development is the nation's declining birthrate which is among the lowest in the world. This is particularly prevalent in parts of society with higher education. As a result, the numbers of workers are expected to decrease and the government spending needed to support pensioners and healthcare will increase if the trend is not reversed.[156]

Less than a quarter of German people expect living conditions to improve in the coming decades.[157]

On August 25, 2020, Federal Statistical Office of Germany revealed that the German economy plunged by 9.7% in the second quarter which is the worst on record. The latest figures show how hard the German economy was hit by the government measures in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.[158]

Energy-intensive German industry and German exporters were hit particularly hard by the 2022 global energy crisis.[159][160] Economy Minister Robert Habeck warned that the planned end of Russian energy imports will permanently raise energy prices for German industry and consumers.[161]

In the early 21st century, German governments supported the European Green Deal and Germany's transition to green energy.[162] Germany planned to phase out coal by 2030.[163] The last three nuclear power plants in Germany were shut down on 15 April 2023.[164][165]

Speaking at the COP28 climate summit in Dubai in December 2023, German Chancellor Olaf Scholz called for a phase-out of fossil fuels, including coal, oil and natural gas, and reiterated Germany's commitment to be climate neutral by 2045, saying, "The technologies are there: wind power, photovoltaics, electric motors, green hydrogen."[166]

Immigration

[edit]In October 2023, Economy Minister Robert Habeck called for more immigration to Germany, saying the shortage of skilled workers was the country's "most pressing structural problem".[167] Net immigration to Germany was 663,000 in 2023, down from a record 1,462,000 in 2022.[168]

Poverty

[edit]In recent decades, poverty in Germany has been increasing. Children are more likely to be poor than adults. There has been a strong increase in the number of poor children. In 1965, only one in 75 children lived on welfare, in 2007 one in 6 did.[169]

Poverty rates differ by states. In 2005, only 6.6% of children and 3.9% of all citizens in states like Bavaria were impoverished. In Berlin, 15.2% of the inhabitants and 30.7% of the children received welfare payments.[170]

The German Kinderhilfswerk, an organization caring for children in need has demanded the government to do something about the poverty problem.

As of 2015, poverty in Germany was at its highest since the German reunification (1990). Some 12.5 million Germans are now classified as poor.[171]Homelessness

[edit]Homelessness in Germany is a significant social issue, one that is estimated to affect around 678,000 people.[172] This figure includes about 372,000 people that are accommodated (in refugee shelters, etc.) by public services, e.g. by the municipalities.[173] Since 2014, there has been a 150% increase in the homeless population within the country.[174] Reportedly, around 22,000 of the homeless population are children.[172][citation needed]

In addition, the country has yet to publish statistics on homelessness at a Federal Level[175] despite it being an ongoing and widespread matter.Climate change

[edit]As a highly industrial, urbanized economy with a relatively short coastline compared to other major economies, the impacts of climate change on Germany are more narrowly focused than other major economies. Germany's traditional industrial regions are typically the most vulnerable to climate change. These are mostly located in the provinces of North Rhine-Westphalia, Saarland, Rhineland-Palatinate, Thuringia, Saxony, Schleswig-Holstein and the free cities of Bremen and Hamburg.[176]

The Rhineland is historically a heavily industrial and population-dense area which includes the states of North Rhine-Westphalia, Rhineland Palatinate, and Saarland. This region is rich in iron and coal deposits and supports one of Europe's largest coal industries. In the past, sulfuric acid emissions from Rhineland coal plants contributed to acid rain, damaging forests in other regions like Hesse, Thuringia, and Saxony.

Other significant problems for the Rhineland related to its high level of industrialization include the destruction of infrastructure from extreme weather events, loss of water for industrial purposes, and fluctuation of the ground water level. Since these problems are related to its level of industrialization, cities within other regions are also sensitive to these challenges including Munich and Bremen.See also

[edit]- Association of German Chambers of Industry and Commerce

- Codetermination in Germany

- Deutsche Bundesbank

- German Federal Association of Young Entrepreneurs

- German model

- Metropolitan regions in Germany

- List of German states by unemployment rate

- List of German cities by GDP

- Trade unions in Germany

- Work–life balance

- Work–life balance in Germany

References

[edit]- ^ "World Economic Outlook Database, April 2019". IMF.org. International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 29 September 2019.

- ^ "World Bank Country and Lending Groups". datahelpdesk.worldbank.org. World Bank. Retrieved 29 September 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "Europe :: Germany". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- ^ a b "Social Expenditure – Aggregated data". OECD.

- ^ a b Kenworthy, Lane (1999). "Do Social-Welfare Policies Reduce Poverty? A Cross-National Assessment" (PDF). Social Forces. 77 (3): 1119–1139. doi:10.2307/3005973. JSTOR 3005973. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 August 2013.

- ^ "Population on 1 January". ec.europa.eu/eurostat. Eurostat. Retrieved 13 July 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "World Economic Outlook database: October 2024". imf.org. International Monetary Fund.

- ^ "People at risk of poverty or social exclusion". ec.europa.eu/eurostat. Eurostat.

- ^ "Gini coefficient of equivalised disposable income - EU-SILC survey". ec.europa.eu/eurostat. Eurostat.

- ^ a b "Human Development Report 2023/2024" (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. 13 March 2024. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 March 2024. Retrieved 28 April 2024.

- ^ "CPI 2023". Transparency International. 30 January 2024. Archived from the original on 4 February 2023. Retrieved 30 January 2024.

- ^ a b c d "August 2020: employment slightly up on the previous month". destatis.de. Federal Statistical Office of Germany. Retrieved 2 October 2020.

- ^ "Employment rate by sex, age group 20-64". ec.europa.eu/eurostat. Eurostat. Retrieved 20 July 2024.

- ^ a b "Export Partners of Germany". The Observatory of Economic Complexity. Retrieved 14 April 2023.

- ^ a b "Import Partners of Germany". The Observatory of Economic Complexity. Retrieved 14 April 2023.

- ^ "Deutsche Bundesbank" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 April 2018. Retrieved 9 July 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f "Provision of deficit and debt data for 2023 - first notification". ec.europa.eu/eurostat. Eurostat. 22 April 2024. Retrieved 28 April 2024.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 December 2017. Retrieved 25 December 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 April 2017. Retrieved 25 December 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Sovereigns rating list". Standard & Poor's. Archived from the original on 28 September 2011. Retrieved 26 May 2011.

- ^ a b c Rogers, Simon; Sedghi, Ami (15 April 2011). "How Fitch, Moody's and S&P rate each country's credit rating". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 1 August 2013. Retrieved 31 May 2011.

- ^ "Scope affirms Germany's AAA rating with Stable Outlook". Retrieved 27 September 2024.

- ^ "Germany Foreign Exchange Reserves". CEIC Data - UK. 2018. Retrieved 5 August 2018.

- ^ Spicka 2007, p. 2.

- ^ "Germany: Spend More At Home". imf.org. Archived from the original on 8 January 2018. Retrieved 28 April 2018.

- ^ Alfred Dupont CHANDLER, Takashi Hikino, Alfred D Chandler, Scale and Scope: The Dynamics of Industrial Capitalism 1990

- ^ "Scale and Scope — Alfred D. Chandler, Jr. | Harvard University Press". Hup.harvard.edu. Archived from the original on 20 November 2014. Retrieved 13 August 2014.

- ^ Ettel, Anja (2 February 2015). "Warum Europa über Deutschlands Erfolg meckert" [Why Europe complains about Germany's success]. Die Welt (in German). Archived from the original on 2 February 2015. Retrieved 3 February 2015.

- ^ "German current account surplus to hit record, world's largest in 2016: Ifo". CNBC. 6 September 2016. Archived from the original on 23 February 2017. Retrieved 22 February 2017.

- ^ "National economy & environment - Foreign trade - Federal Statistical Office (Destatis)". Archived from the original on 13 November 2015.

- ^ Statistisches Bundesamt: Ranking of Germany's trading partners in foreign trade: 2014 Archived 21 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine, 22 October 2015

- ^ "Country Profile: Germany". Macro Trends. p. 1.

- ^ "Germany's capital exports under the euro | vox". Voxeu.org. 2 August 2011. Archived from the original on 22 February 2014. Retrieved 13 August 2014.

- ^ Destatis. "CIA Factbook". Archived from the original on 2 May 2015. Retrieved 23 April 2015.

- ^ "What Germany offers the world". The Economist. 14 April 2012. Archived from the original on 28 April 2018. Retrieved 28 April 2018.

- ^ "How Does Germany do It?". Archived from the original on 2 September 2017. Retrieved 29 April 2017.

- ^ Moller, Stephanie; Huber, Evelyne; Stephens, John D.; Bradley, David; Nielsen, François (2003). "Determinants of Relative Poverty in Advanced Capitalist Democracies". American Sociological Review. 68 (1): 22–51. doi:10.2307/3088901. JSTOR 3088901.

- ^ Burger, Bruno (15 January 2020). "Public Net Electricity Generation in Germany 2019" (PDF). ise.fraunhofer.de. Freiburg, Germany: Fraunhofer Institute for Solar Energy Systems ISE. Retrieved 11 February 2020.

- ^ Wind Power Archived 10 December 2006 at the Wayback Machine Federal Ministry of Economics and Technology (Germany) Retrieved 30 November 2006.

- ^ "Electricity production in the 2nd quarter of 2019: nearly half of the electricity supplied was produced from renewables". Destatis. Retrieved 4 November 2019.

- ^ a b "Germany: The World's First Major Renewable Energy Economy". Archived from the original on 29 March 2015. Retrieved 24 February 2024.

- ^ a b Fraunhofer ISE, Electricity production from solar and wind in Germany – New record in wind power production, p.2 15 December 2014

- ^ "World Official Gold Holdings - International Financial Statistics, March 2024". World Gold Council. 5 March 2024. Retrieved 8 March 2024.

- ^ Our World in Data. "Research & development spending as a share of GDP". ourworldindata.org. Retrieved 10 January 2024.

- ^ Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. "Gross domestic spending on R&D". data.oecd.org. Archived from the original on 14 January 2017. Retrieved 10 January 2024.

- ^ "High-technology exports". World Bank Open Data. Retrieved 15 April 2023.

- ^ "Anteile Kleine und Mittlere Unternehmen 2021 nach Größenklassen in %". Statistisches Bundesamt (in German). Retrieved 22 February 2024.

- ^ Bayley, Caroline (17 August 2017). "Germany's 'hidden champions' of the Mittelstand". BBC News. Archived from the original on 22 May 2019.

- ^ "Leading car manufacturers by revenue 2022".

- ^ "Forbes Global 2000: Germany's Largest Companies". Forbes. Archived from the original on 8 April 2015. Retrieved 29 March 2018.

- ^ "DHL Group - Umsatz bis 2022".

- ^ "Global 500 2023". Fortune. Retrieved 24 December 2023.

- ^ "Members to the Supervisory Board of Deutsche Bahn AG". Archived from the original on 25 October 2012.

- ^ "Deutsche Bahn AG at a glance". Deutsche Bahn. Archived from the original on 26 April 2009.

- ^ "10 biggest retailers in the world". Forbes. Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- ^ "trade shows in Germany, fairs Germany, trade fair Germany, trade show venue Germany". Archived from the original on 29 July 2014.

- ^ "Trade fairs in Germany". German National Tourist Board. Archived from the original on 2 February 2014. Retrieved 5 February 2014.

- ^ Compare: Mitchell, Allan (2006). Great Train Race: Railways and the Franco-German Rivalry, 1815–1914. Berghahn Books. pp. 54–55. ISBN 9781845451363.

There were until [1870] [...] only the beginnings of a nexus of technological innovation and economic growth, the erratic construction of a platform for what might later be justifiably termed a take-off in Germany. But there is little evidence within the given chronological framework for a full-blown notion of an Industrial Revolution [...].

- ^ Richard Tilly, "Germany: 1815–1870" in Rondo Cameron, ed. Banking in the Early Stages of Industrialization: A Study in Comparative Economic History (Oxford University Press, 1967), pages 151-182

- ^ Cornelius Torp, "The "Coalition of 'Rye and Iron'" under the Pressure of Globalization: A Reinterpretation of Germany's Political Economy before 1914," Central European History Sept 2010, Vol. 43 Issue 3, pp 401-427

- ^ "Class and Politics in Germany, 1850 to 1900". Archived from the original on 23 April 2015.

- ^ "Germany - history - geography". Archived from the original on 3 May 2015.

- ^

"Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 June 2016. Retrieved 2 February 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ a b c J. Bradford DeLong (February 1997). "Slouching Towards Utopia?: The Economic History of the Twentieth Century -XV. Nazis and Soviets-". University of California at Berkeley and NBER. Archived from the original on 11 May 2008. Retrieved 15 August 2007.

- ^ Gaettens, Richard (1982). Geschichte der Inflationen : vom Altertum bis zur Gegenwart (Nachdr. ed.). München: Battenberg. pp. 279–298. ISBN 3-87045-211-0.

- ^ Lee, Stephen (1996). Weimar and Nazi Germany. Oxford: Heinemann. p. 63. ISBN 043530920X.

- ^ Hans-Joachim Braun, "The German Economy in the Twentieth Century", Routledge, 1990, p. 101

- ^ Lee, Stephen (1996). Weimar and Nazi Germany. Oxford: Heinemann. p. 60. ISBN 043530920X.

- ^ Hans-Joachim Braun, "The German Economy in the Twentieth Century", Routledge, 1990, p. 102

- ^ Arthur Schweitzer, "Big Business in the Third Reich", Bloomington, Indiana University Press, 1964, p. 288

- ^ Reynoldson, Fiona (1996). Weimar and Nazi Germany (Foundation ed.). Oxford: Heinemann. p. 49. ISBN 0435308602.

- ^ Norman M. Naimark. The Russians in Germany: A History of the Soviet Zone of Occupation, 1945–1949. Harvard University Press, 1995. ISBN 0-674-78405-7 pp. 167-9

- ^ a b Boyes, Roger (24 August 2007). "Germany starts recovery from €2,000bn union". Times Online. London. Archived from the original on 29 May 2010. Retrieved 12 October 2009.

- ^ Bruttoinlandsprodukt (Vierteljahres- und Jahresangaben) Archived 13 November 2010 at the Wayback Machine Statistisches Bundesamt.

- ^ a b c d "CIA Factbook: Germany". Cia.gov. Retrieved 13 August 2014.

- ^ Hopkins, Kathryn (14 November 2008). "Germany officially in recession as OECD expects US to lead recovery". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 4 September 2013. Retrieved 1 May 2010.

- ^ Thesing, Gabi (13 November 2008). "bloomberg.com, German Economy Enters Worst Recession in 12 Years". Bloomberg.com. Archived from the original on 13 June 2010. Retrieved 13 August 2014.

- ^ German economy falls into recession Archived 23 July 2016 at the Wayback Machine, New York Times, 2008-11-13

- ^ "Germany agrees on 50-billion-euro stimulus plan". France 24. 6 January 2009. Archived from the original on 13 May 2011.

- ^ "Country Comparison :: Exports". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. ISSN 1553-8133. Archived from the original on 28 October 2013. Retrieved 9 August 2012.

- ^ "Country Comparison :: Imports". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. ISSN 1553-8133. Archived from the original on 4 October 2008. Retrieved 9 August 2012.

- ^ a b c CIA. "CIA Factbook". Retrieved 2 August 2009.

- ^ "Wind Power". Federal Ministry of Economics and Technology. Archived from the original on 10 December 2006. Retrieved 27 March 2011.

- ^ UFI, the Global Association of the Exhibition Industry (2008). "Euro Fair Statistics 2008" (PDF). AUMA Ausstellungs- und Messe-Ausschuss der Deutschen Wirtschaft e.V. p. 12. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 July 2011. Retrieved 24 September 2011.

- ^ "Defying the Euro Crisis". Spiegel Online. 27 December 2011. Archived from the original on 27 December 2011.

- ^ Brain Drain Feared as German Jobs Lure Southern Europeans Archived 26 January 2017 at the Wayback Machine 28 April 2012

- ^ "Germany went from envy of the world to the worst-performing major developed economy. What happened?". AP News. 19 September 2023. Retrieved 23 October 2023.

- ^ a b "How did Germany fare without Russian gas?". Brookings. Retrieved 28 December 2023.

- ^ "Scholz and liberal finance minister clash over nuclear phase-out". Euractiv. 9 June 2022.

- ^ "How Bad Will the German Recession Be?". Der Spiegel. 14 September 2022.

- ^ "Economic Key Facts Germany". 5 December 2023.

- ^ "Ahead of Scholz trip, study shows German economy still dependent on China". Reuters.

- ^ "Report for Selected Countries and Subjects".

- ^ "The 100 Top Brands 2010". Interbrand. Archived from the original on 12 February 2011. Retrieved 27 March 2011.

- ^ "The power of SMEs". Facts about Germany. Retrieved 2 June 2021.

- ^ Gavin, Mike (23 September 2010). "Germany Has 1,000 Market-Leading Companies, Manager-Magazin Says". Businessweek. New York. Archived from the original on 30 April 2011. Retrieved 27 March 2011.

- ^ "Statistics on Mergers & Acquisitions (M&A) - M&A Courses | Company Valuation Courses | Mergers & Acquisitions Courses". Imaa-institute.org. Archived from the original on 6 January 2012. Retrieved 13 August 2014.

- ^ "Statistics on Mergers & Acquisitions (M&A) - M&A Courses | Company Valuation Courses | Mergers & Acquisitions Courses". Imaa-institute.org. Archived from the original on 6 January 2012. Retrieved 13 August 2014.

- ^ Frost, Simon (28 August 2015). "Berlin outranks London in start-up investment". euractiv.com. Archived from the original on 6 November 2015. Retrieved 28 October 2015.

- ^ "Industry Breakdown of Companies in Germany". HitHorizons.

- ^ "Global 500: Countries – Germany". Forbes. 26 July 2010. Archived from the original on 23 March 2011. Retrieved 27 March 2011.

- ^ "Information and Statistics about Mergers & Acquisitions (M&A) Germany". IMAA-Institute. Archived from the original on 22 February 2018. Retrieved 22 February 2018.

- ^ a b c Gürtler, Detlef: Wirtschaftsatlas Deutschland. Rowohlt Berlin, 2010

- ^ Berg, S., Winter, S., Wassermann, A. The Price of a Failed Reunification Archived 20 November 2007 at the Wayback Machine Spiegel Online International. 5 September 2005. Retrieved 28 November 2006.

- ^ "Germany may become 22nd EU state with federal minimum wage". Germany News.Net. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 7 July 2014.

- ^ Stickings, Tim (25 May 2023). "Germany slides into recession as high prices hit home". The National. Retrieved 21 June 2023.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "The World's Billionaires". Forbes. Archived from the original on 3 April 2013. Retrieved 4 July 2016.

- ^ "These Are Germany's Power Cities". 12 August 2013. Archived from the original on 13 March 2014. Retrieved 1 March 2014.

- ^ "CPI 2009 table". Transparency International. Retrieved 18 November 2009.

- ^ "The Innovation Imperative in Manufacturing: How the United States Can Restore Its Edge" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 November 2009. Retrieved 26 September 2010.

- ^ "German Economy Experiences Record Growth in 2010" German Embassy Press Release 12 January 2011 Archived 1 November 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Germany - Agricultural Production and Forest Cover | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 25 June 2023.

- ^ 31.7% —or about 11,076,000 hectares— of Germany is forested Archived 21 February 2010 at the Wayback Machine, mongabay.com, 2005.

- ^ a b c d Gürtler, Detlef: Wirtschaftsatlas Deutschland. Rowohlt Berlin, 2010.

- ^ "USGS Selenium Production Statistics" (PDF).

- ^ "USGS Potash Production Statistics" (PDF).

- ^ "USGS Boron Production Statistics" (PDF).

- ^ "USGS Lime Production Statistics" (PDF).

- ^ "USGS Fluorspar Production Statistics" (PDF).

- ^ "USGS Fluorspar Production Statistics" (PDF).

- ^ "USGS Graphite Production Statistics" (PDF).

- ^ "USGS Sulfur Production Statistics" (PDF).

- ^ "USGS Salt Production Statistics" (PDF).

- ^ "'We are a car country': German conservatives commit to reverse combustion engine ban". Euractiv. 11 March 2024.

- ^ Venohr, Bernd; Meyer, Klaus E. (2007). "The German Miracle Keeps Running: How Germany's Hidden Champions Stay Ahead in the Global Economy" (PDF). Working Paper 30. FHW Berlin. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 March 2009. Retrieved 9 October 2009.

- ^ Venohr, Bernd (2010). "The power of uncommon common sense management principles - The secret recipe of German Mittelstand companies - Lessons for large and small companies" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 October 2011. Retrieved 8 December 2010.

- ^ Wall, Robert (17 March 2013). "China Replaces U.K. in Top-Five Arms Exporters Headed by U.S." Bloomberg.com. Archived from the original on 13 August 2014. Retrieved 13 August 2014.

- ^ "Interim Update" (PDF). UNWTO World Tourism Barometer. UNWTO. April 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 January 2015. Retrieved 26 June 2011.

- ^ "UNWTO Annual Report 2010" (PDF). UNWTO. 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 June 2014.

- ^ Zahlen Daten Fakten 2012 Archived 1 January 2015 at the Wayback Machine (in German), German National Tourist Board

- ^ "Tourism Highlights 2014 edition" (PDF). UNWTO. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 February 2015. Retrieved 26 March 2015.

- ^ "2013 Travel & Tourism Economic Impact Report Germany" (PDF). WTTC. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

- ^ "Wind Power". Archived from the original on 10 December 2006. Retrieved 27 March 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) Federal Ministry of Economics and Technology (Germany) Retrieved 30 November 2006. - ^ "World Economic Outlook Database, April 2015, General government gross debt (National currency, Per cent of GDP)". International Monetary Fund. April 2015. Archived from the original on 5 February 2016. Retrieved 26 January 2016.

- ^ "Third quarter of 2015 compared with second quarter of 2015 - Government debt fell to 91.6 % of GDP in euro area". Eurostat. 22 January 2016. Archived from the original on 24 January 2016. Retrieved 26 January 2016.

- ^ "German Government Achieves 'Historic' Budget Surplus". The World Street Journal. 13 January 2016. Archived from the original on 13 March 2016. Retrieved 26 January 2016.

- ^ "Reuters: Fitch Affirms Germany at 'AAA'; Outlook Stable". Reuters. 8 January 2016. Archived from the original on 2 February 2016. Retrieved 26 January 2016.

- ^ Buck, Tobias (4 January 2018). "German 'debt clock' reverses for first time in 20 years". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 4 January 2018. Retrieved 4 January 2018.

- ^ "German and European Economic Policy | IGM Forum". Archived from the original on 25 February 2020.

- ^ "Greentech – A Sector with a Future". Facts about Germany.

- ^ "Germany split over green energy". 25 February 2005 – via news.bbc.co.uk.

- ^ a b Welle, Deutsche. "Germany: Coal tops wind as primary electricity source | DW | 13.09.2021". DW.COM. Retrieved 28 October 2021.

- ^ "Energy Consumption in Germany" (in German). Archived from the original on 27 April 2011. Retrieved 13 August 2014.

- ^ Detlef, Günter: Wirtschaftsatlas Deutschland. Rowohlt Berlin, 2010. p.42

- ^ "Germany's Autobahn faces blanket speed limits". May 2013. Archived from the original on 20 October 2014.

- ^ "Geschäftsbericht 2006 der Deutschen Bahn AG". Archived from the original on 9 August 2007. Retrieved 27 March 2011., Deutsche Bahn. Retrieved 19 October 2007.

- ^ "German Railway Financing" (PDF). p. 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 March 2016.

- ^ Isabella Bufacchi (27 April 2019). "From Deutsche to Sparkassen, the 3 "plastered" pillars of German banks".

- ^ "In which European countries do you save the most?".[permanent dead link]

- ^ Research in Germany Archived 20 August 2010 at the Wayback Machine German Embassy, New Delhi. Retrieved 2010-28-08.

- ^ "Germany's Technological Performance". Federal Ministry of Education and Research. 11 January 2007. Archived from the original on 25 August 2011. Retrieved 21 August 2011.

- ^ Roland Berger Strategy Consultants: Green Growth, Green Profit – How Green Transformation Boosts Business Palgrave Macmillan, New York 2010, ISBN 978-0-230-28543-9

- ^ Industry strongly engaged in research Archived 21 November 2011 at the Wayback Machine Facts about Germany. Retrieved 2010-29-08.

- ^ Thomasson, Emma (28 July 2017). "Asleep at the wheel? Germany frets about economic car crash". reuters.com. Archived from the original on 1 October 2017. Retrieved 28 April 2018.

- ^ "EU countries approve 2035 phaseout of CO2-emitting cars". Reuters. 29 March 2023.

- ^ Debt 'explosion' awaits unless policymakers defuse demographic timebomb, warns IMF chief Archived 3 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine, The Telegraph. Retrieved 2016-6-03.

- ^ The Economist, March 28, 2020, page 4.

- ^ "German economy plunges by record 9.7%". DW. Retrieved 25 August 2020.

- ^ "A Grave Threat to Industry in Germany". Der Spiegel. 21 September 2022.

- ^ "How Bad Will the German Recession Be?". Der Spiegel. 14 September 2022.

- ^ "Germany's Era of Cheap Energy Is Over, Economy Minister Says". The Wall Street Journal. 2 May 2022.

- ^ "EU ministers approve landmark climate measures, but tough talks await". Politico. 29 June 2022.

- ^ "Germany's Habeck Hopeful on Switching Off Coal Plants". Bloomberg. 3 November 2023.

- ^ "Germany has shut down its last three nuclear power plants, and some climate scientists are aghast". NBC News. 18 April 2023.

- ^ "After scrapping nuclear reactors, Germany to spend billions on new gas power plants". Politico. 5 February 2024.

- ^ "COP28: Germany's Scholz calls to phase out coal, oil and gas". Deutsche Welle. 2 December 2023.

- ^ "Germany calls for more immigrants to fix its shrinking economy". Financial Times. 11 October 2023.

- ^ "Germany: Net immigration sinks sharply in 2023". Deutsche Welle. 27 June 2024.

- ^ "Sozialhilfe: Kinderarmut nimmt zu". Focus. 15.11.2007.

- ^ "Poverty in Germany". World Socialist Website. Retrieved 2014-13-05.

- ^ "Poverty in Germany at its highest since reunification". Deutsche Welle. 19 February 2015. Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- ^ a b "Homelessness in Germany on the rise". DW.COM. 11 November 2019. Archived from the original on 31 January 2020. Retrieved 31 January 2020.

- ^ "Statistics of homeless people accommodated". Statistisches Bundesamt. Archived from the original on 10 January 2024. Retrieved 10 January 2024.

- ^ "Germany: 150 percent rise in number of homeless since 2014". DW.COM. 14 November 2017. Archived from the original on 17 February 2020. Retrieved 17 February 2020.

- ^ "OHCHR | Home". ohchr.org. Archived from the original on 5 May 2021. Retrieved 31 January 2020.

- ^ Rannow, Sven; Loibl, Wolfgang; Greiving, Stefan; Gruehn, Dietwald; Meyer, Burghard C. (30 December 2010). "Potential impacts of climate change in Germany—Identifying regional priorities for adaptation activities in spatial planning". Landscape and Urban Planning. Climate Change and Spatial Planning. 98 (3): 160–171. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2010.08.017.

Notes

[edit]Further reading

[edit]- Spicka, Mark E. (2007). Selling the Economic Miracle: Reconstruction and Politics in West Germany. Berghahn Books. ISBN 978-1-84545-223-0.