Le Morte d'Arthur

This article may require copy editing for grammar, style, cohesion, tone, or spelling. (October 2024) |

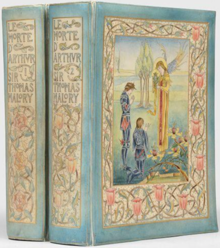

The two volumes of an illustrated edition of Le Morte D'Arthur published by J. M. Dent in 1893, with vellucent binding by Cedric Chivers | |

| Author | Thomas Malory |

|---|---|

| Original title | Le morte Darthur |

| Language | Middle English |

| Subject | Matter of Britain |

| Genre | Chivalric romance, sword and sorcery, historical fantasy |

| Published | 1485 |

| Publisher | William Caxton |

| Publication place | Kingdom of England |

| 823.2 | |

| LC Class | PR2043 .B16 |

| Text | Le Morte d'Arthur at Wikisource |

Le Morte d'Arthur (originally written as le morte Darthur; Anglo-Norman French for "The Death of Arthur")[1] is a 15th-century Middle English prose reworking by Sir Thomas Malory of tales about the legendary King Arthur, Guinevere, Lancelot, Merlin and the Knights of the Round Table, along with their respective folklore. In order to tell a "complete" story of Arthur from his conception to his death, Malory compiled, rearranged, interpreted and modified material from various French and English sources. Today, this is one of the best-known works of Arthurian literature. Many authors since the 19th-century revival of the legend have used Malory as their principal source.

Apparently written in prison at the end of the medieval English era, Le Morte d'Arthur was completed by Malory around 1470 and was first published in a printed edition in 1485 by William Caxton. Until the discovery of the Winchester Manuscript in 1934, the 1485 edition was considered the earliest known text of Le Morte d'Arthur and that closest to Malory's original version.[2] Modern editions under myriad titles are inevitably variable, changing spelling, grammar and pronouns for the convenience of readers of modern English, as well as often abridging or revising the material.

History

[edit]Authorship

[edit]The exact identity of the author of Le Morte d'Arthur has long been the subject of speculation, as at least six historical figures bore the name of "Sir Thomas Malory" (in various spellings) during the late 15th century.[3] In the work, the author describes himself as "Knyght presoner Thomas Malleorre" ("Sir Thomas Maleore" according to the publisher William Caxton). Historically, this has been taken as supporting evidence for the identification most widely accepted by scholars: that the author was Thomas Malory of Newbold Revel, Warwickshire,[4][5] son of Sir John Malory.

According to the timeline proposed by P.J.C. Field, Sir Thomas of Newbold Revel inherited the family estate in 1434, but by 1450 he was fully engaged in a life of crime. As early as 1433, he had been accused of theft, but the more serious allegations against him included that of the attempted murder of Humphrey Stafford, 1st Duke of Buckingham, an accusation of at least two rapes, and that he had attacked and robbed Coombe Abbey. Malory was first arrested and imprisoned in 1451 for the ambush of Buckingham, but was released early in 1452. By March, he was back in the Marshalsea prison and then in Colchester, escaping on multiple occasions. In 1461, he was granted a pardon by King Henry VI, returning to live at his estate. After 1461, however, few records survive which scholars agree refer to Malory of Newbold Revel. In 1468–1470, King Edward IV issued four more general pardons which specifically excluded a Thomas Malory. The first of these named Malory a knight and applied to participants in a campaign in Northumberland in the North of England by members of the Lancastrian faction. Field interprets these pardon-exclusions to refer to Malory of Newbold Revel, suggesting that Malory changed his allegiance from York to Lancaster, and that he was involved in a conspiracy with Richard Neville, 16th Earl of Warwick to overthrow King Edward. William Matthews, having given evidence of this candidate's advanced age at the time of the Northumberland campaign and living much further to the South, interprets this record as referring to his own proposed candidate for authorship. Field proposed that it was during a final stint at Newgate Prison in London that he wrote Le Morte d'Arthur,[6] and that Malory was released in October 1470 when Henry VI returned to the throne, dying only five months later.[4] This Warwickshire knight was widely accepted as the author of the Morte until the publication of Matthews' research in 1966.

This identification was widely accepted through most of the 20th century based on the assumption that this candidate was born around 1416. The 1416 date was proposed by Field, contradicting the original record of this knight's military service record by Dugdale.[7] In 1966, Matthews published original research demonstrating that Malory of Newbold Revel had in fact been an officer under King Henry V in the famous Agincourt campaign by 1414 or 1415; confirming Dugdale's original record and placing this knight's birth around 1393. Some late 20th-century researchers cast a doubt that this would make the Newbold Revel knight far too old to have written Le Morte: in prison in his mid-70s to early 80s, when, in Matthews' words, "the medieval view was that by sixty a man was bean fodder and forage, ready for nothing but death's pit."[8] Because no other contemporary Thomas Malory had been shown to have been knighted, the question remained unresolved.

The second candidate to receive scholarly support as the possible author of Le Morte Darthur is Thomas Mallory of Papworth St Agnes in Huntingdonshire, whose will, written in Latin and dated 16 September 1469, was described in an article by T. A. Martin in the Athenaeum magazine in September 1897.[9] This Mallory was born in Shropshire in 1425, the son of Sir William Mallory, although there is no indication in the will that he was himself a knight; he died within six weeks of the will being made. It has been suggested that the fact that he appears to have been brought up in Lincolnshire may account for the traces of Lincolnshire dialect in Le Morte Darthur.[10] To date, this candidate has not commanded the attention of scholars as the Newbold-Revel knight has.

The most recent contender for authorship emerged in the mid-20th century: Thomas Malory of Hutton Conyers and Studley Royal in Yorkshire. This claim was put forward in 1966 in The Ill-Framed Knight: A Skeptical Inquiry into the Identity of Sir Thomas Malory by William Matthews.[11] Matthews' primary arguments in favor of the Yorkshire Malory were the northerly dialect of the Morte; the likelihood that this is the Malory who was excluded from the pardon by Edward IV in 1468; and the fact that the Newbold Revel knight was far too old to be writing the Morte in the late 1460s. Matthews' interpretation was not widely accepted, primarily because he could not find evidence that the Yorkshireman was a knight. Cecelia Lampp Linton, however, has provided extensive detail about the Malorys of Yorkshire and offered evidence that Thomas of Yorkshire was a Knight Hospitaller, a militant of the Catholic Church.[12] She has also examined the provenance of some of the known sources of the Morte and has demonstrated that this Malory would have had ready access to these documents. Accepting Linton's evidence would remove the primary objection to his authorship, making the contradictions presented by the Newbold Revel knight irrelevant. The Morte itself seems to be much more the work of a knight of the church than a secular repeat offender, as evidenced by Malory's own conclusion (rendered in Modern English): "... pray for me while I am in life that God send me good deliverance, and when I am dead I pray you all pray for my soul; for this book was ended the ninth year of the reign of King Edward the Fourth by Sir Thomas Maleore, knight, as Jesus help him by his great might, as he is the servant of Jesus both day and night."[13]

Sources

[edit]

As Elizabeth Bryan wrote of Malory's contribution to Arthurian legend in her introduction to a modern edition of Le Morte d'Arthur, "Malory did not invent the stories in this collection; he translated and compiled them. Malory in fact translated Arthurian stories that already existed in 13th-century French prose (the so-called Old French Vulgate romances) and compiled them together with Middle English sources (the Alliterative Morte Arthure and the Stanzaic Morte Arthur) to create this text."[14]

Within his narration, Malory refers to drawing it from a singular "Freynshe booke", in addition to also unspecified "other bookis".[15] In addition to the vast Vulgate Cycle in its different variants, as well as the English poems Morte Arthur and Morte Arthure, Malory's other original source texts were identified as several French standalone chivalric romances, including Érec et Énide, L'âtre périlleux, Perlesvaus, and Yvain ou le Chevalier au Lion (or its English version, Ywain and Gawain), as well as John Hardyng's English Chronicle.[16] The English poem The Weddynge of Syr Gawen is uncertainly regarded as either just another of these or possibly actually Malory's own work.[17] His assorted other sources might have included a 5th-century Roman military manual, De re militari.[18]

Publication and impact

[edit]Le Morte d'Arthur was completed in 1469 or 1470 ("the ninth year of the reign of King Edward IV"), according to a note at the end of the book.[19] It is believed that Malory's original title intended was to be The hoole booke of kyng Arthur & of his noble knyghtes of the rounde table, and only its final section to be named Le Morte Darthur.[20] At the end of the work, Caxton added: "Thus endeth this noble & joyous book entytled le morte Darthur, Notwythstondyng it treateth of the byrth, lyf, and actes of the sayd kynge Arthur; of his noble knyghtes of the rounde table, theyr meruayllous enquestes and aduentures, thachyeuyng of the sangreal, & in thende the dolorous deth & departynge out of this worlde of them al." Caxton separated Malory's eight books into 21 books, subdivided the books into a total of 506[21] chapters, and added a summary of each chapter as well as a colophon to the entire book.[22] In his preface, Caxton also discussed the subject of the historicity of King Arthur.[23]

The first printing of Malory's work was made by Caxton in 1485, becoming one of the first books to be ever printed in England.[24] Only two copies of this original printing are known to exist, in the collections of the Morgan Library & Museum in New York and the John Rylands Library in Manchester.[25] It proved popular and was reprinted in an illustrated form with some additions and changes in 1498 (The Boke of Kyng Arthur Somtyme Kynge of Englande and His Noble Actes and Feates of Armes of Chyvalrye) and 1529 (The Boke of the Moost Noble and Worthy Prince Kyng Arthur Somtyme Kyng of Grete Brytayne Now Called Englande) by Wynkyn de Worde who succeeded to Caxton's press. Three more editions were published before the English Civil War: William Copland's The Story of the Most Noble and Worthy Kynge Arthur (1557), Thomas East's The Story of Kynge Arthur, and also of his Knyghtes of the Rounde Table (1585), and William Stansby's The Most Ancient and Famous History of the Renowned Prince Arthur King of Britaine (1634), each of which contained additional changes and errors. Stansby's edition, based on East's, was also deliberately censored.[26] Thereafter, the book went out of fashion until the Romanticist revival of interest in all things medieval.

The British Library summarizes the importance of Malory's work thus: "It was probably always a popular work: it was first printed by William Caxton (...) and has been read by generations of readers ever since. In a literary sense, Malory's text is the most important of all the treatments of Arthurian legend in English language, influencing writers as diverse as Edmund Spenser, Alfred, Lord Tennyson, Mark Twain and John Steinbeck."[20]

The Winchester Manuscript

[edit]

An assistant headmaster at Winchester College, Walter Fraser Oakeshott discovered a previously unknown manuscript copy of the work in June 1934, during the cataloguing of the college's library. Newspaper accounts announced that what Caxton had published in 1485 was not exactly what Malory had written.[27] Oakeshott published "The Finding of the Manuscript" in 1963, chronicling the initial event and his realization that "this indeed was Malory," with "startling evidence of revision" in the Caxton edition.[28] This manuscript is now in the British Library's collection.[29]

Malory scholar Eugène Vinaver examined the manuscript shortly after its discovery. Oakeshott was encouraged to produce an edition himself, but he ceded the project to Vinaver.[28] Based on his initial study of the manuscript, Oakeshott concluded in 1935 that the copy from which Caxton printed his edition "was already subdivided into books and sections."[30] Vinaver made an exhaustive comparison of the manuscript with Caxton's edition and reached similar conclusions. Microscopic examination revealed that ink smudges on the Winchester manuscript are offsets of newly printed pages set in Caxton's own font, which indicates that the Winchester Manuscript was in Caxton's print shop. The manuscript is believed to be closer on the whole to Malory's original and does not have the book and chapter divisions for which Caxton takes credit in his preface. It has been digitised by a Japanese team, who note that "the text is imperfect, as the manuscript lacks the first and last quires and few leaves. The most striking feature of the manuscript is the extensive use of red ink."[31][32]

In his 1947 publication of The Works of Sir Thomas Malory, Vinaver argued that Malory wrote not a single book, but rather a series of Arthurian tales, each of which is an internally consistent and independent work. However, William Matthews pointed out that Malory's later tales make frequent references to the earlier events, suggesting that he had wanted the tales to cohere better but had not sufficiently revised the whole text to achieve this.[33] This was followed by much debate in the late 20th-century academia over which version is superior, Caxton's print or Malory's original vision.[34]

Caxton's edition differs from the Winchester manuscript in many places. As well as numerous small differences on every page, there is also a major difference both in style and content in Malory's Book II (Caxton's Book V), describing the war with the Emperor Lucius, where Caxton's version is much shorter. In addition, the Winchester manuscript has none of the customary marks indicating to the compositor where chapter headings and so on were to be added. It has therefore been argued that the Winchester manuscript was not the copy from which Caxton prepared his edition; rather it seems that Caxton either wrote out a different version himself for the use of his compositor, or used another version prepared by Malory.[35]

The Winchester manuscript does not appear to have been copied out by Malory himself; rather, it seems to have been a presentation copy made by two scribes who, judging from certain dialect forms which they introduced into the text, appear to have come from West Northamptonshire. Apart from these forms, both the Winchester manuscript and the Caxton edition show some more northerly dialect forms which, in the judgement of the Middle English dialect expert Angus McIntosh are closest to the dialect of Lincolnshire. McIntosh argues, however, that this does not necessarily rule out the Warwickshire Malory as the possible author; he points out that it could be that the Warwickshire Malory consciously imitated the style and vocabulary of romance literature typical of the period.[36]

Content overview

[edit]Setting and themes

[edit]

Most of the events take place in a historical fantasy version of Britain and France at an unspecified time (on occasion, the plot ventures farther afield, to Rome and Sarras, and recalls Biblical tales from the ancient Near East). Arthurian myth is set during the 5th to 6th centuries; however, Malory's telling contains many anachronisms and makes no effort at historical accuracy–even more so than his sources. Earlier romance authors have already depicted the "Dark Ages" times of Arthur as a familiar, High-to-Late Medieval style world of armored knights and grand castles taking place of the Post-Roman warriors and forts. Malory further modernized the legend by conflating the Celtic Britain with his own contemporary Kingdom of England (for example explicitly identifying Logres as England, Camelot as Winchester, and Astolat as Guildford) and, completely ahistorically, replacing the legend's Saxon invaders with the Ottoman Turks in the role of King Arthur's foreign pagan enemies.[37][38] Malory hearkens back to an age of knighthood, with chivalric codes of honour and jousting tournaments, and as noted by Ian Scott-Kilvert, characters which "consist almost entirely of fighting men, their wives or mistresses, with an occasional clerk or an enchanter, a fairy or a fiend, a giant or a dwarf," and "time does not work on the heroes of Malory."[39]

According to Charles W. Moorman III, Malory intended "to set down in English a unified Arthuriad which should have as its great theme the birth, the flowering, and the decline of an almost perfect earthy civilization." Moorman identified three main motifs going through the work: Sir Lancelot's and Queen Guinevere's affair; the long blood feud between the families of King Lot and King Pellinore; and the mystical Grail Quest. Each of these plots would define one of the causes of the downfall of Arthur's kingdom, namely "the failures in love, in loyalty, in religion."[40] Beverly Kennedy opined that the central theme of the work is that of adultery, from the begetting of Arthur to the cause of his fall.[41] Much of the Malory scholarship is concerned specifically with the issues relating to the subject of Lancelot and Guinevere's adultery.[42]

Volumes and internal chronology

[edit]

Prior to Caxton's reorganization, Malory's work originally consisted of eight volumes (one of them was also divided into two parts). The following list uses Winchester Manuscript (Malory's "Syr" is usually rendered "Sir" today) as well as William Caxton's print edition and modern titles by Arthurian scholars Eugène Vinaver and P. J. C. Field:

- The birth and rise of Arthur: Fro the Maryage of Kynge Uther unto Kyng Arthure that Regned Aftir Hym and Ded Many Batayles (Caxton's Books I–IV, Vinaver's The Tale of King Arthur, Field's King Uther and King Arthur)

- Arthur's war against the resurgent Western Romans: The Noble Tale betwyxt Kynge Arthure and Lucius the Emperour of Rome, alternatively The Tale of the Noble Kynge Arthure That Was Emperoure Hymself thorow Dygnyté of His Hondys (Caxton's Book V, Vinaver's The Tale of the Noble King Arthur That Was Emperor Himself through Dignity of His Hands, Field's King Arthur and the Emperor Lucius)

- The early adventures of Lancelot: The Noble Tale of Syr Launcelot du Lake (Caxton's Book VI, Field's Sir Launcelot du Lake)

- The story of Gareth: The Tale of Syr Gareth of Orkeney That Was Called Beaumayns by Syr Kay (Caxton's Book VII, Vinaver's The Tale of Sir Gareth of Orkney That Was Called Bewmaynes, Field's Sir Gareth of Orkney)

- The legend of Tristan and Iseult: The Fyrste Boke of Syr Trystram de Lyones and The Secunde Boke of Syr Trystram de Lyones (Caxton's Books VIII–XII, Vinaver's The Book of Sir Tristram de Lyones, Field's Sir Tristram de Lyones: The First Book and Sir Tristram de Lyones: The Second Book)

- The quest for the Grail: The Tale of the Sankgreal (Caxton's Books XIII–XVII, Field's The Sankgreal)

- The forbidden love between Lancelot and Guinevere: Syr Launcelot and Quene Gwenyvere (Caxton's Books XVIII–XIX, Vinaver's The Book of Sir Launcelot and Queen Guinevere, Field's Sir Launcelot and Queen Guenivere)

- The breakup of the Knights of the Round Table and the last battle of Arthur: The Moste Pyteuous Tale of Le Morte d'Arthur Saunz Gwerdon [meaning Without Reward, usually corrected to saunz Guerdon] (Caxton's Books XX–XXI, Vinaver's The Death of King Arthur or The Most Piteous Tale of the Morte Arthur saunz Guerdon; also known as The Death of Arthur in modern scholarship)

Moorman attempted to put the books of the Winchester Manuscript in chronological order. In his analysis, Malory's intended chronology can be divided into three parts: Book I followed by a 20-year interval that includes some events of Book V (Lancelot and Elaine - from the meeting of the two to the madness of Lancelot); the 15-year-long period of Book V, also spanning Books IV (takes place after the adventure of the Cote de Mal Tale), II (takes place between King Mark and Alexander the Orphan), and III (takes place between Alexander the Orphan and the Tournament of Surluse); Lancelot meets Bliant after the Tournament of Lonezep towards the end of Lancelot and Elaine section; the section of Sir Palomides takes place after Lancelot returns to Arthur's court; and finally Books VI, VII, and VIII in a straightforward sequence beginning with the closing part of Book V (the conclusion section).[43]

Style

[edit]Like other English prose in the 15th century, Le Morte d'Arthur was highly influenced by French writings, but Malory blends these with other English verse and prose forms. The Middle English of Le Morte d'Arthur is much closer to Early Modern English than the Middle English of Geoffrey Chaucer's Canterbury Tales (the publication of Chaucer's work by Caxton was a precursor to Caxton's publication of Malory); if the spelling is modernised, it reads almost like Elizabethan English. Where the Canterbury Tales are in Middle English, Malory extends "one hand to Chaucer, and one to Spenser,"[44] by constructing a manuscript that is hard to place in one category. His writing can be divisive today, often regarded by critics (including prominent scholars such as Vinaver, George Saintsbury, Robert Lumiansky, C.S Lewis, and E. K. Chambers) as simplistic and unsophisticated from an artistic viewpoint.[45] Conversely, there are also opposite opinions, even regarding it a "supreme aesthetic accomplishment" (William Carlin).[46] For a modern audience, his prose may feel better when modernised (and perhaps especially when also dramatically performed aloud) than as it reads in its original form.[47]

Other aspects of Malory's writing style include his abrupt abridging of much of the source material, especially in the early parts concerning Arthur's backstory and his rise to power (preferring the later adventures of the knights), apparently acting on an authorial assumption that the reader knows the story already and resulting in the problem of omitting important things "thereby often rendering his text obscure", and how he would sometimes turn descriptions of characters into proper names.[48][49] Because there is so much lengthy ground to cover, Malory uses "so—and—then", often to transition his retelling of the stories that become episodes instead of instances that can stand on their own.[50]

Synopsis and analysis

[edit]Book I (Caxton I–IV)

[edit]

Arthur is born to the High King of Britain (Malory's "England") Uther Pendragon and his new wife Igraine, and then taken by the wizard Merlin to be secretly fostered by Arthur's uncle Ector in the country in turmoil after the death of Uther. Years later, the now teenage Arthur suddenly becomes the ruler of the leaderless Britain when he removes the fated sword from the stone in the contest set up by Merlin, which proves his birthright that he himself had not been aware of. The newly crowned King Arthur and his followers including King Ban and King Bors go on to fight against rivals and rebels, ultimately winning the war in the great Battle of Bedegraine. Arthur prevails due to his military prowess and the prophetic and magical counsel of Merlin (later eliminated and replaced by the sorceress Nimue), further helped by the sword Excalibur that Arthur received from a Lady of the Lake. With the help of reconciled rebels, Arthur also crushes a foreign invasion in the Battle of Clarence. With his throne secure, Arthur marries the also young Princess Guinevere and inherits the Round Table from her father, King Leodegrance. He then gathers his chief knights, including some of his former enemies who now joined him, at his capital Camelot and establishes the Round Table fellowship as all swear to the Pentecostal Oath as a guide for knightly conduct.

It also includes the tale of Balyn and Balan (a lengthy section which Malory called a "booke" in itself), as well as some other episodes, such as King Pellinore's hunt for the Questing Beast and the treason of Arthur's sorceress half-sister Queen Morgan le Fay in the plot involving her lover Accolon. Furthermore, it tells of begetting of Arthur's incestuous son Mordred by one of his other royal half-sisters, Morgause (though Arthur did not know her as his sister). On Merlin's advice, Arthur then takes away every newborn boy in his kingdom and all of them but Mordred (who miraculously survives and eventually indeed will kill his father in the end) perish at sea; this is mentioned matter-of-factly, with no apparent moral overtone.

The narrative of the first book is mainly based on the Prose Merlin in its version from the Post-Vulgate Suite du Merlin (possibly the manuscript Cambridge University Library, Additional 7071[51]).[16] Malory addresses his contemporary preoccupations with legitimacy and societal unrest, which will appear throughout the rest of Le Morte d'Arthur.[52] His concern reflects the 15th-century England, where many were claiming their rights to power through violence and bloodshed. According to Helen Cooper in Sir Thomas Malory: Le Morte D'arthur – The Winchester Manuscript, the prose style, which mimics historical documents of the time, lends an air of authority to the whole work. This allowed contemporaries to read the book as a history rather than as a work of fiction, therefore making it a model of order for Malory's violent and chaotic times during the Wars of the Roses, arguably resembling his contemporary John Vale's Book.[53]

Book II (Caxton V)

[edit]The opening of the second volume finds Arthur and his kingdom without an enemy. His throne is secure, and his knights including Griflet and Tor as well as Arthur's own nephews Gawain and Ywain (sons of Morgause and Morgan, respectively) have proven themselves in various battles and fantastic quests as told in the first volume. Seeking more glory, Arthur and his knights then go to the war against (fictitious) Emperor Lucius who has just demanded Britain to resume paying tribute. Departing from Geoffrey of Monmouth's literary tradition in which Mordred is left in charge (as this happens there near the end of the story), Malory's Arthur leaves his court in the hands of Constantine of Cornwall and sails to Normandy to meet his cousin Hoel. After that, the story details Arthur's march on Rome through Almaine (Germany) and Italy. Following a series of battles resulting in the great victory over Lucius and his allies, and the Roman Senate's surrender, Arthur is crowned a Western Emperor but instead arranges a proxy government and returns to Britain.

This book is based mostly on the first half of the Middle English heroic poem Alliterative Morte Arthure (itself heavily based on Geoffrey's pseudo-chronicle Historia Regum Britanniae). Caxton's print version is abridged by more than half compared to Malory's manuscript.[54] Vinaver theorized that Malory originally wrote this part first as a standalone work, while without knowledge of French romances.[55] In effect, there is a time lapse that includes Arthur's war against King Claudas in France.

Book III (Caxton VI)

[edit]

Going back to a time before Book II, Malory establishes Lancelot, a young French orphan prince, as King Arthur's most revered knight through numerous episodic adventures, some of which he presented in comedic manner.[56] Lancelot always adheres to the Pentecostal Oath, assisting ladies in distress and giving mercy for honourable enemies he has defeated in combat. However, the world Lancelot lives in is too complicated for simple mandates and, although Lancelot aspires to live by an ethical code, the actions of others make it difficult.

Lancelot's character had previously appeared in the chronologically later Book II, fighting for Arthur against the Romans. In Book III, based on parts of the French Prose Lancelot (mostly its 'Agravain' section, along with the chapel perilous episode taken from Perlesvaus),[16][57][58] His character is widely regarded as of central importance to the entire work, representing "the very paradigm of Malorian knighthood".[59] Malory attempts to turn the focus of courtly love from adultery to service by having Lancelot dedicate doing everything he does for Queen Guinevere, the wife of his lord and friend Arthur, but avoid (for a time being) to committing to an adulterous relationship with her. Nevertheless, it is still her love that is the ultimate source of Lancelot's supreme knightly qualities, something that Malory himself did not appear to be fully comfortable with as it seems to have clashed with his personal ideal of knighthood.[60] Although a catalyst of the fall of Camelot, as it was in the French romantic prose cycle tradition, the moral handling of the adultery between Lancelot and Guinevere in Le Morte implies their relationship is true and pure, as Malory focused on the ennobling aspects of courtly love. Other issues are demonstrated when Morgan enchants Lancelot, which reflects a feminization of magic, and in how the prominence of jousting tournament fighting in this tale indicates a shift away from battlefield warfare towards a more mediated and virtuous form of violence.

Book IV (Caxton VII)

[edit]

The fourth volume primarily deals with the adventures of the young Gareth ("Beaumains") in his long quest for the sibling ladies Lynette and Lioness. The youngest of Arthur's nephews by Morgause and King Lot, Gareth hides his identity as a nameless squire at Camelot as to achieve his knighthood in the most honest and honourable way.[61] While this particular story is not directly based on any existing text unlike most of the content of previous volumes, it resembles various Arthurian romances of the Fair Unknown type.[62]

Book V (Caxton VIII–XII)

[edit]A long collection of the tales about Tristan of Lyonesse as well as a variety of other knights such as Dinadan, Lamorak, Palamedes, Alexander the Orphan (Tristan's young relative abducted by Morgan), and "La Cote de Male Tayle". After telling of Tristan's birth and childhood, its primary focus is on the doomed adulterous relationship between Tristan and the Belle Isolde, wife of his villainous uncle King Mark. It also includes the retrospective story of how Galahad was fathered by Lancelot to Princess Elaine of Corbenic, followed by Lancelot's years of madness.

Based mainly on the French vast Prose Tristan, or its lost English adaptation (and possibly also the Middle English verse romance Sir Tristrem[63]), Malory's treatment of the legend of the young Cornish prince Tristan is the centerpiece of Le Morte d'Arthur as well as the longest of his eight books, constituting a third of the entire work. The variety of episodes, and the alleged lack of structural coherence in the Tristan narrative,[64] raised questions about its role in Malory's text. Vinaver condemned it as "long and monotonous" and suggested it to be left for the last, his view shared by much of classic scholarship.[65] Others, conversely, have since praised or at very least partially approved of the book, arguably an essential reading due to how Malory foreshadows and prepares for the rest of his work by developing or forecasting a variety of characters, themes, and tales found in the later books.[66] It can be seen as an exploration of secular chivalry and a discussion of earthly "worship" (in the meaning of glory and reputation) when it is founded in a sense of shame and honor.[67][68] If Le Morte is viewed as a text in which Malory is attempting to define the concept of knighthood, then the tale of Tristan becomes its critique, rather than Malory attempting to create an ideal knight as he does in some of the other books.

Book VI (Caxton XIII–XVII)

[edit]

Malory's primary source for this long part was the Vulgate Queste del Saint Graal, chronicling the adventures of many Knights of the Round Table in their mostly separate, pilgrimage-like journeys to find the Holy Grail. Gawain is the first to embark on the search for the Grail, followed by others including Lancelot who likewise undergo the quest, traveling either in small groups of changing composition or alone. Their martial and spiritual exploits are intermingled with encounters with maidens and hermits who offer advice and interpret dreams along the way. It is ultimately achieved by Galahad and his final companions, Percival and Bors the Younger.

After the confusion of the secular moral code he manifested within the previous book, Malory attempts to construct a new mode of chivalry by placing an emphasis on religion, albeit somewhat less than his French sources did, the degree of difference depending on an interpretation.[69] As in the Queste, the framework for the interactions between the Grail knights (Galahad, Percival, and Bors) is based on Saint Aelred's ideas from his book Spiritual Friendship.[70] Christianity and the Church offer a venue through which the Pentecostal Oath can be upheld, whereas the strict moral code imposed by religion foreshadows almost certain failure on the part of the knights. For instance, Gawain refuses to do penance for his sins, claiming the tribulations that coexist with knighthood as a sort of secular penance. Likewise, the flawed Lancelot, for all his sincerity, is unable to completely escape his adulterous love of Guinevere, and is thus destined to fail where Galahad will succeed. This coincides with the personification of perfection in the form of Galahad, a virgin wielding the power of God. Galahad's life, uniquely entirely without sin, makes him a model of a holy knight that cannot be emulated through secular chivalry. Nevertheless, in contrast to the striking condemnation and humiliation of Lancelot's character in the Queste, Malory's version of the Knight of the Lake continues to be the paragon of, at least, earthly honor.[71]

Book VII (Caxton XVIII–XIX)

[edit]Following the quest for the Holy Grail, Lancelot tries to maintain his knightly virtues but finds himself drawn back into his illicit romance with Guinevere. He stays true to her, tragically rejecting the desperate love of Elaine of Ascolat, and completes a series of trials that culminates in his rescue of the Queen from the abduction by the renegade knight Maleagant (this is also the first time the work explicitly mentions the couple's sexual adultery).

Writing it, Malory combined the established material from the Vulgate Cycle's early Prose Lancelot (including its abridged retelling of Lancelot, the Knight of the Cart), and the early parts of the Vulgate Mort Artu, with his own creations (the episodes "The Great Tournament" and "The Healing of Sir Urry").[72][73] A key theme emphasised at the end of each of the book's five tales is forgiveness.[74]

Book VIII (Caxton XX–XXI)

[edit]

A disaster strikes when King Arthur's bastard son Mordred and his half-brother Agravain succeed in revealing Queen Guinevere's adultery and Arthur sentences her to burn. Lancelot's rescue party raids the execution, killing several loyal knights of the Round Table, including, unwittingly, Gawain's younger brothers Gareth and Gaheris. Gawain, bent on revenge, prompts Arthur into a long and bitter civil war with Lancelot. After they leave to pursue Lancelot in France, where Gawain is mortally injured in a duel with Lancelot (and later finally reconciles with him on his death bed), Mordred seizes the throne and takes control of Arthur's kingdom. At the bloody final battle between Mordred's followers and Arthur's remaining loyalists in England, Arthur kills Mordred but is himself gravely wounded. As Arthur is dying, the lone survivor Bedivere casts Excalibur away, and Morgan and Nimue come together to take Arthur to Avalon. Following the disappearance and presumed passing of King Arthur, who is succeeded by Constantine, Malory provides a short epilogue about the later lives and deaths of Bedivere, Guinevere, and Lancelot and his kinsmen.

Writing the eponymous final book, Malory used the version of Arthur's death derived primarily from parts of the Vulgate Mort Artu and, as a secondary source,[75] from the English Stanzaic Morte Arthur (or, in another possibility, a hypothetical now-lost French modification of the Mort Artu was a common source of both of these texts[76]). In the words of George Brown, the book "celebrates the greatness of the Arthurian world on the eve of its ruin. As the magnificent fellowship turns violently upon itself, death and destruction also produce repentance, forgiveness, and salvation."[77]

Modern versions and adaptations

[edit]

Following the lapse of 182 years since the last printing, the year 1816 saw a new edition by Alexander Chalmers, illustrated by Thomas Uwins (The History of the Renowned Prince Arthur, King of Britain; with His Life and Death, and All His Glorious Battles. Likewise, the Noble Acts and Heroic Deeds of His Valiant Knights of the Round Table), as well as another one by Joseph Haslewood (La Mort D'Arthur: The Most Ancient and Famous History of the Renowned Prince Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table); both of these were based on the 1634 Stansby's version. Several other modern editions, including these by Thomas Wright (La Morte D'Arthure: The History of King Arthur and of the Knights of the Round Table, 1858) and Ernest Rhys (Malory's History of King Arthur and the Quest of The Holy Grail: From The Morte D'Arthur, 1886), were also based on that by Stansby.[78][79]

William Upcott's edition directly based on then-newly rediscovered Morgan copy of the first print Caxton version was published as Malory's Morte d'Arthur with Robert Southey's introduction and notes including summaries of the original French material from the Vulgate tradition in 1817. Afterwards, Caxton became the basis for many subsequent editions until the 1934 discovery of the Winchester Manuscript.

The first mass-printed modern edition of Caxton was published in 1868 by Edward Strachey as a book for boys titled Le Morte Darthur: Sir Thomas Malory's Book of King Arthur and His Noble Knights of the Round Table, highly censored in accordance to Victorian morals. Many other 19th-century editors, abridgers and retellers such as Henry Frith (King Arthur and His Knights of the Round Table, 1884) would also censor their versions for the same reason.[80] The first "standard" popular edition, based on Caxton was Heinrich Oskar Sommer's Le Morte Darthur by Syr Thomas Malory published in 1890 with an introduction and glossary as well as an essay on Malory's prose style, followed by these by John Rhys in 1893 (Everyman's Library) and Israel Gollancz in 1897 (Temple Classics).[78][79]

Modernized editions update the late Middle English spelling, update some pronouns, and re-punctuate and re-paragraph the text. Others furthermore update the phrasing and vocabulary to contemporary Modern English. The following sentence (from Caxton's preface, addressed to the reader) is an example written in Middle English and then in Modern English:

- Doo after the good and leve the evyl, and it shal brynge you to good fame and renomme.[81] (Do after the good and leave the evil, and it shall bring you to good fame and renown.[82])

Since the 19th-century Arthurian revival, there have been numerous modern republications, retellings and adaptations of Le Morte d'Arthur. A few of them are listed below (see also the following Bibliography section):

- Malory's book inspired Reginald Heber's unfinished poem Morte D'Arthur. A fragment of it was published by Heber's widow in 1830.[83]

- Victorian poet Alfred Tennyson retold the legends in the poetry volume Idylls of the King (1859 and 1885). His work focuses on Le Morte d'Arthur and the Mabinogion, with many expansions, additions and several adaptations, such as the fate of Guinevere (in Malory, she is sentenced to be burnt at the stake but is rescued by Lancelot; in the Idylls, Guinevere flees to a convent, is forgiven by Arthur, repents and serves in the convent until her death).

- James Thomas Knowles published Le Morte d'Arthur as The Legends of King Arthur and His Knights in 1860. Knowles described it as "an abridgment of Sir Thomas Malory's version ... with a few additions from Geoffrey of Monmouth and other sources—and an endeavor to arrange the many tales into a more or less consecutive story."[84] Originally illustrated by George Housman Thomas, it has been subsequently illustrated by various other artists, including William Henry Margetson and Louis Rhead. The 1912 edition was illustrated by Lancelot Speed, who later also illustrated Rupert S. Holland's 1919 King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table that was based on Knowles with addition of some material from the 12th-century Perceval, the Story of the Grail.

- In 1880, Sidney Lanier published a much expurgated rendition entitled The Boy's King Arthur: Sir Thomas Malory's History of King Arthur and His Knights of the Round Table, Edited for Boys,[85] an enduringly popular children's adaptation, originally illustrated by Alfred Kappes. A new edition with illustrations by N. C. Wyeth was first published in 1917. This version was later incorporated into Grosset and Dunlap's series of books called the Illustrated Junior Library, and reprinted under the title King Arthur and his Knights of the Round Table (1950).[86]

- In 1892, London publisher J. M. Dent produced an illustrated edition of Le Morte Darthur in modern spelling, with illustrations by 20-year-old insurance office clerk and art student Aubrey Beardsley. It was issued in 12 volumes between June 1893 and mid-1894, and met with only modest success, but was later described as Beardsley's first masterpiece, launching what has come to be known as the "Beardsley look".[87] It was Beardsley's first major commission, and included nearly 585 chapter openings, borders, initials, ornaments and full- or double-page illustrations. The majority of the Dent edition illustrations were reprinted by Dover Publications in 1972 under the title Beardsley's Illustrations for Le Morte Darthur. A facsimile of the Beardsley edition, complete with Malory's unabridged text, was published in the 1990s.

- Mary MacLeod's popular children's adaptation King Arthur and His Noble Knights: Stories From Sir Thomas Malory's Morte D'Arthur was first published with illustrations by Arthur George Walker in 1900 and subsequently reprinted in various editions and in extracts in children's magazines.

- Beatrice Clay wrote a retelling first included in her Stories from Le Morte Darthur and the Mabinogion (1901). A retitled version, Stories of King Arthur and the Round Table (1905), features illustrations by Dora Curtis.[88]

- In 1902, Andrew Lang published The Book of Romance, a retelling of Malory illustrated by Henry Justice Ford. It was retitled as Tales of King Arthur and the Round Table in the 1909 edition.

- Howard Pyle wrote and illustrated a series of four books: The Story of King Arthur and His Knights (1903), The Story of the Champions of the Round Table (1905), The Story of Sir Launcelot and His Companions (1907), and The Story of the Grail and the Passing of King Arthur (1910). Rather than retell the stories as written, Pyle presented his own versions of select episodes enhanced with other tales and his own imagination.

- Another children's adaptation, Henry Gilbert's King Arthur's Knights: The Tales Retold for Boys and Girls, was first published in 1911, originally illustrated by Walter Crane. Highly popular, it was reprinted many times until 1940, featuring also illustrations from other artists such as Frances Brundage and Thomas Heath Robinson.

- Alfred W. Pollard published an abridged edition of Malory in 1917, illustrated by Arthur Rackham. Pollard later also published a complete version in four volumes during 1910–1911 and in two volumes in 1920, with illustrations by William Russell Flint.

- T. H. White's The Once and Future King (1938–1977) is a famous and influential retelling of Malory's work. White rewrote the story in his own fashion. His rendition contains intentional and obvious anachronisms and social-political commentary on contemporary matters. White made Malory himself a character and bestowed upon him the highest praise.[89]

- Pollard's 1910–1911 abridged edition of Malory provided basis for John W. Donaldson's 1943 book Arthur Pendragon of Britain. It was illustrated by N. C. Wyeth son, Andrew Wyeth.

- Roger Lancelyn Green's book King Arthur and His Knights of the Round Table was published in 1953, with illustrations by the filmmaker Lotte Reiniger. This retelling is based mainly on Malory, but includes tales from other sources such as Sir Gawain and the Green Knight and The Wedding of Sir Gawain and Dame Ragnelle.

- Alice Mary Hadfield retold the stories as King Arthur and the Round Table (1953), with illustrations by Donald Seton Cammell, in the series "The Children's Illustrated Classics," published by Dent /Dutton.

- Alex Blum's comic book retelling Knights of the Round Table was published in the Classics Illustrated series in 1953.

- John Steinbeck utilized the Winchester Manuscripts of Thomas Malory and other sources as the original text for his The Acts of King Arthur and His Noble Knights. This retelling was intended for young people but was never completed. It was published posthumously in 1976 as The Book of King Arthur and His Noble Knights of the Round Table.

- Walker Percy credited his childhood reading of The Boy's King Arthur for his own novel Lancelot (1977).

- Thomas Berger described his 1978 novel Arthur Rex as his memory of the "childish version" by Elizabeth Lodor Merchant that began his fascination in the Arthurian legend in 1931.[90]

- Excalibur, a 1981 British film directed, produced, and co-written by John Boorman, retells Le Morte d'Arthur, with some changes to the plot and fate of certain characters (such as merging Morgause with Morgan, who dies in this version).

- Marion Zimmer Bradley's 1983 The Mists of Avalon retold Le Morte d'Arthur from a feminist neopagan perspective.

- In 1984, the ending of Malory's story was turned by John Barton and Gillian Lynne into a BBC2 non-speaking (that is featuring only Malory's narration and silent actors) television drama, titled simply Le Morte d'Arthur.

- Emma Gelders Sterne, Barbara Lindsay, Gustaf Tenggren and Mary Pope Osborne published King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table in 2002.

- Jeff Limke's and Tom Yeates' comic book adaptation of a part of Malory's Book I was published as King Arthur: Excalibur Unsheathed in 2006, followed by Arthur & Lancelot: The Fight for Camelot in 2007.

- Castle Freeman Jr.'s 2008 novel Go with Me is a modern retelling of Malory's Tale of Sir Gareth.[91][92]

- In 2009, Dorsey Armstrong published a Modern English translation that focused on the Winchester manuscript rather than the Caxton edition.

- Peter Ackroyd's 2010 novel The Death of King Arthur is a modern English retelling of Le Morte d'Arthur.[93]

- Chris Crawford's 2023 game Le morte D'Arthur features interactive story where one plays for Arthur and decides about course of action.[94]

Bibliography

[edit]The work itself

[edit]Editions based on the Winchester manuscript

[edit]- Facsimile:

- Malory, Sir Thomas. The Winchester Malory: A Facsimile. Introduced by Ker, N. R. (1976). London: Early English Text Society. ISBN 0-19-722404-0.

- Original spelling:

- Sir Thomas Malory: Le Morte Darthur: The Definitive Original Text Edition (D. S. Brewer) Ed. Field, Rev. P. J. C. (19 May 2017). ISBN 978-1-843-84460-0

- Sir Thomas Malory: Le Morte Darthur (2 volume set) (Arthurian Studies) (D. S. Brewer) Ed. Field, Rev. P. J. C. Illustrated edition (20 April 2015). ISBN 978-1-843-84314-6

- Malory, Sir Thomas. Le Morte Darthur. (A Norton Critical Edition). Ed. Shepherd, Stephen H. A. (2004). New York: W. W. Norton. ISBN 0-393-97464-2

- _________. The Works of Sir Thomas Malory. Ed. Vinaver, Eugène. 3rd ed. Field, Rev. P. J. C. (1990). 3 vol. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-812344-2, 0-19-812345-0, 0-19-812346-9.

- _________. Malory: Complete Works. Ed. Vinaver, Eugène (1977). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-281217-3. (Revision and retitling of Malory: Works of 1971).

- _________. Malory: Works. Ed. Vinaver, Eugène (1971). 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-254163-3.

- _________. The Works of Sir Thomas Malory. Ed. Vinaver, Eugène (1967). 2nd ed. 3 vol. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-811838-4.

- _________. Malory: Works. Ed. Vinaver, Eugène (1954). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-254163-3. (Malory's text from Vinaver's The Works of Sir Thomas Malory (1947), in a single volume dropping most of Vinaver's notes and commentary.)

- _________. The Works of Sir Thomas Malory. Ed. Vinaver, Eugène (1947). 3 vol. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Modernised spelling:

- Malory, Sir Thomas. Le Morte Darthur: The Winchester Manuscript. Ed. Cooper, Helen (1998). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-282420-1 (Abridged text.)

- Brewer, D.S. Malory: The Morte Darthur. York Medieval Texts, Elizabeth Salter and Derek Pearsall, Gen. Eds. (1968) London: Edward Arnold. Reissued 1993. ISBN 0-7131-5326-1. (Modernised spelling version of Books 7 (except The Poisoned Apple) and 8 as a complete story in its own right. Based on Winchester MS but with changes taken from Caxton and some emendations by Brewer.)

The Winchester Manuscript Edition has not been modernised fully yet but there are some partial and abridged modernisations of the text.

- Translation/paraphrase into contemporary English:

- Armstrong, Dorsey. Sir Thomas Malory's Morte Darthur: A New Modern English Translation Based on the Winchester Manuscript (Renaissance and Medieval Studies) Anderson, SC: Parlor Press, 2009. ISBN 1-60235-103-1.

- Malory, Sir Thomas. Malory's Le Morte D'Arthur: King Arthur and Legends of the Round Table. Trans. and abridged by Baines, Keith (1983). New York: Bramhall House. ISBN 0-517-02060-2. Reissued by Signet (2001). ISBN 0-451-52816-6.

- _________. Le Morte D'Arthur. (London Medieval & Renaissance Ser.) Trans. Lumiansky, Robert M. (1982). New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. ISBN 0-684-17673-4.

- John Steinbeck, and Thomas Malory. The Acts of King Arthur and His Noble Knights: From the Winchester Manuscripts of Thomas Malory and Other Sources. (1976) New York: Noonday Press. Reissued 1993. ISBN 0-374-52378-9. (Unfinished)

Editions based on Caxton's edition

[edit]- Facsimile:

- Malory, Sir Thomas. Le Morte d'Arthur, printed by William Caxton, 1485. Ed. Needham, Paul (1976). London.

- Original spelling:

- Malory, Sir Thomas. Caxton's Malory. Ed. Spisak, James. W. (1983). 2 vol. boxed. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-03825-8.

- _________. Le Morte Darthur by Sir Thomas Malory. Ed. Sommer, H. Oskar (1889–91). 3 vol. London: David Nutt. The text of Malory from this edition without Sommer's annotation and commentary and selected texts of Malory's sources.

- _________. Tales of King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table. Caxton's text, with illustrations by Aubrey Beardsley and a foreword by Sarah Peverley (2017). Flame Tree Publishing. ISBN 978-1786645517.

- –––. Le Morte Darthur, Corpus of Middle English Prose and Verse: University of Michigan.

- Modernised spelling:

- Malory, Sir Thomas. Le Morte d'Arthur. Ed. Matthews, John (2000). Illustrated by Ferguson, Anna-Marie. London: Cassell. ISBN 0-304-35367-1. (The introduction by John Matthews praises the Winchester text but then states this edition is based on the Pollard version of the Caxton text, with eight additions from the Winchester manuscript.)

- _________. Le Morte Darthur. Introduction by Moore, Helen (1996). Herefordshire: Wordsworth Editions Ltd. ISBN 1-85326-463-6. (Seemingly based on the Pollard text.)

- _________. Le morte d'Arthur. Introduction by Bryan, Elizabeth J. (1994). New York: Modern Library. ISBN 0-679-60099-X. (Pollard text.)

- _________. Le Morte d'Arthur. Ed. Cowen, Janet (1970). Introduction by Lawlor, John. 2 vols. London: Penguin. ISBN 0-14-043043-1, 0-14-043044-X.

- _________. Le Morte d'Arthur. Ed. Rhys, John (1906). (Everyman's Library 45 & 46.) London: Dent; London: J. M. Dent; New York: E. P. Dutton. Released in paperback format in 1976: ISBN 0-460-01045-X, 0-460-01046-8. (Text based on an earlier modernised Dent edition of 1897.)

- _________. Le Morte Darthur: Sir Thomas Malory's Book of King Arthur and of his Noble Knights of the Round Table,. Ed. Pollard, A. W. (1903). 2 vol. New York: Macmillan. (Text corrected from the bowdlerised 1868 Macmillan edition edited by Sir Edward Strachey.)

- _________. Le Morte Darthur. Ed. Simmon, F. J. (1893–94). Illustrated by Beardsley, Aubrey. 2 vol. London: Dent.

- Project Gutenberg: Le Morte Darthur: Volume 1 (books 1–9) and Le Morte Darthur: Volume 2 (books 10–21). (Plain text.)

- Electronic Text Center, University of Virginia Library: Le Morte Darthur: Volume 1 (books 1–9) and Le Morte Darthur: Volume 2 (books 10–21) (HTML.)

- Celtic Twilight: Legends of Camelot: Le Morte d'Arthur (HTML with illustrations by Aubrey Beardsley from the Dent edition of 1893–94.)

Commentary

[edit]- Glossary to Le Morte d'Arthur at Glossary to Book 1 and Glossary to Book 2 (PDF)

- Malory's Morte d'Arthur and Style of the Morte d'Arthur, selections by Alice D. Greenwood with bibliography from the Cambridge History of English Literature.

- Arthur Dies at the End by Jeff Wikstrom

- About the Winchester manuscript:

- University of Georgia: English Dept: Jonathan Evans: Walter F. Oakeshott and the Winchester Manuscript. (Contains links to the first public announcements concerning the Winchester manuscript from The Daily Telegraph, The Times, and The Times Literary Supplement.)

- UBC Dept. of English: Siân Echard: Caxton and Winchester (link offline on Oct. 25, 2011; according to message on Ms. Echard's Medieval Pages, "September 2011: Most of the pages below are being renovated, so the links are (temporarily) inactive.")

- Department of English, Goucher College: Arnie Sanders: The Malory Manuscript

Other

[edit]- Bryan, Elizabeth J. (1999/1994). "Sir Thomas Malory", Le Morte D'Arthur, p. v. New York: Modern Library. ISBN 0-679-60099-X.

- Lumiansky, R. M. (1987). "Sir Thomas Malory's Le Morte Darthur, 1947-1987: Author, Title, Text". Speculum Vol. 62, No. 4 (Oct., 1987), pp. 878–897. The University of Chicago Press on behalf of the Medieval Academy of America

- Whitteridge, Gweneth (1973). "The Identity of Sir Thomas Malory, Knight-Prisoner". The Review of English Studies. 24 (95): 257–265. doi:10.1093/res/XXIV.93.257. ISSN 0034-6551. JSTOR 514968.

- Linton, Cecelia Lampp. The Knight Who Gave Us King Arthur: Sir Thomas Malory, Knight Hospitaller. Front Royal, VA: Christendom College Press. 2023. ISBN 979-8-9868157-2-5.

See also

[edit]- Illegitimacy in fiction – In Le Morte d'Arthur, King Arthur is conceived illegitimately when his father Uther Pendragon utilizes Merlin's magic to seduce Igraine

- James Archer – one of 19th-century British artists inspired by Malory's book

Notes and references

[edit]- ^ The article le would be ungrammatical in modern French since morte (or mort) is a feminine noun, for which French requires the article la (i.e., "la mort d'Arthur"). According to Stephen Shepherd, "Malory frequently misapplies le in titular compounds, perhaps on a simple sonic and gender-neutral analogy with 'the'." Stephen H. A. Shepherd, ed., Le Morte Darthur, by Sir Thomas Malory (New York: Norton, 2004), 1n. However, in Anglo-Norman, "the feminine la was often reduced to le, especially in the later period" (thirteenth century and later), Mildred K. Pope, From Latin to Modern French with Especial Consideration of Anglo-Norman: Phonology and Morphology (Manchester UK: University Press, 1934), paragraph 1252.iii (p. 30).

- ^ Bryan, Elizabeth J. (1994–1999). Introduction. Le morte d'Arthur. By Malory, Thomas (Modern Library ed.). New York: Modern Library. p. vii. ISBN 0-679-60099-X.

- ^ Bryan 1994–1999, p. v

- ^ a b Wight, Colin (2009). "Thomas Malory's 'Le Morte Darthur'". www.bl.uk.

- ^ Whitteridge 1973, pp. 257–265

- ^ Davidson, Roberta (2004). "Prison and Knightly Identity in Sir Thomas Malory's "Morte Darthur"". Arthuriana. 14 (2): 54–63. doi:10.1353/art.2004.0066. JSTOR 27870603. S2CID 161386973.

- ^ Dugdale, Sir Thomas. The Antiquities of Warwickshire Illustrated: From Records, Lieger-Books, Manuscripts, Charters, Evidences, Tombes, and Armes, Beautified with Maps, Prospects, and Portraitures. London: Thomas Warren, 1656.

- ^ Matthews, William (23 September 2022). The III-Framed Knight: A Skeptical Inquiry into the Identity of Sir Thomas Malory. Univ of California Press. ISBN 9780520373365.

- ^ Athenaeum 11 September 1897, p. 353.

- ^ Lumiansky (1987), p. 882.

- ^ Matthews, William (1960). The Ill-Framed Knight: A Skeptical Inquiry into the Identity of Sir Thomas Malory. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press.

- ^ Linton, Cecelia Lampp (2023). The Knight Who Gave Us King Arthur: Sir Thomas Malory, Knight Hospitaller. Front Royal, VA: Christendom College Press. ISBN 979-8-9868157-2-5.

- ^ Parini, Jay (2002). British Writers: Retrospective supplement. C. Scribner's Sons. ISBN 978-0-684-31228-6.

- ^ Bryan (1994), pp. viii–ix.

- ^ Davidson, Roberta (2008). "The 'Freynshe booke' and the English Translator: Malory's 'Originality' Revisited". Translation and Literature. 17 (2): 133–149. doi:10.3366/E0968136108000198. JSTOR 40340096. S2CID 170477682.

- ^ a b c Norris, Ralph C. (2008). Malory's Library: The Sources of the Morte Darthur. DS Brewer. ISBN 9781843841548.

- ^ Lacy, Norris J.; Wilhelm, James J. (2015-07-17). The Romance of Arthur: An Anthology of Medieval Texts in Translation. Routledge. ISBN 9781317341840.

- ^ Bornstein, Diane D. (1972). "Military Strategy in Malory and Vegetius' "De re militari"". Comparative Literature Studies. 9 (2): 123–129. JSTOR 40245989.

- ^ Lumiansky (1987), p. 878. This note is available only in the Morgan Library & Museum version of the book, since in the Winchester manuscript and the John Rylands Library copy the final pages are missing.

- ^ a b "British Library".

- ^ Lumiansky (1987), p. 887 footnote.

- ^ Bryan (2004), p. ix

- ^ https://www.jstor.org/stable/27870602

- ^ "From Monmouth to Malory: A Guide to Arthurian Literature". May 29, 2022.

- ^ McShane, Kara L. (2010). "Malory's Morte d'Arthur". The Rossell Hope Robbins Library at the University of Rochester. Retrieved 3 July 2013.

- ^ Leitch, Megan G.; Rushton, Cory (May 20, 2019). A New Companion to Malory. Boydell & Brewer. ISBN 9781843845232 – via Google Books.

- ^ W. F. Oakeshott. "The Text of Malory". Archived from the original on 2008-07-03. Retrieved 2009-01-11.

- ^ a b Walter F. Oakeshott, "The Finding of the Manuscript," Essays on Malory, ed. J. A. W. Bennett (Oxford: Clarendon, 1963), 1–6.

- ^ "British Library". www.bl.uk.

- ^ Walter F. Oakeshott, "Caxton and Malory's Morte Darthur," Gutenberg-Jahrbuch (1935), 112–116.

- ^ "The Malory Project directed by Takako Kato and designed by Nick Hayward". www.maloryproject.com.

- ^ Whetter, K. S. (2017). The Manuscript and Meaning of Malory's Morte Darthur. D. S. Brewer.

- ^ William Matthews, The Ill-Framed Knight: A Skeptical Inquiry into the Identity of Sir Thomas Malory (Berkeley, CA: University of California, 1966).

- ^ Salda, Michael N. (1995). "Caxton's Print vs. the Winchester Manuscript: An Introduction to the Debate on Editing Malory's Morte Darthur". Arthuriana. 5 (2): 1–4. doi:10.1353/art.1995.0026. JSTOR 27869113. S2CID 161529058.

- ^ Lumiansky (1987), pp. 887–896; Lumiansky favours the view that Malory himself revised the text.

- ^ E. F. Jacob, Angus McIntosh (1968) Review of The Ill-framed Knight. A Skeptical Inquiry into the identity of Sir Thomas Malory by William Matthews. Medium Aevum Vol. 37, No. 3, pp. 347–8.

- ^ Goodrich, Peter H. (2006). "Saracens and Islamic Alterity in Malory's "Le Morte Darthur"". Arthuriana. 16 (4): 10–28. doi:10.1353/art.2006.0009. JSTOR 27870786. S2CID 161861263.

- ^ Murrin, Michael (1997). History and Warfare in Renaissance Epic. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226554051.

- ^ Scott-Kilvert, Ian. British Writers. Charles Scribners's Sons, New York 1979.

- ^ Moorman, Charles (1960). "Courtly Love in Malory". ELH. 27 (3): 163–176. doi:10.2307/2871877. JSTOR 2871877.

- ^ https://www.jstor.org/stable/27869288

- ^ https://www.jstor.org/stable/4174740

- ^ Moorman, Charles (1961). "Internal Chronology in Malory's "Morte Darthur"". The Journal of English and Germanic Philology. 60 (2): 240–249. JSTOR 27713803.

- ^ "§4. Style of the "Morte d'Arthur". XIV. English Prose in the Fifteenth Century. II. Vol. 2. The End of the Middle Ages. The Cambridge History of English and American Literature: An Encyclopedia in Eighteen Volumes. 1907–21". www.bartleby.com. 25 June 2022.

- ^ Lynch, Andrew (2006). "A Tale of 'Simple' Malory and the Critics". Arthuriana. 16 (2): 10–15. doi:10.1353/art.2006.0065. JSTOR 27870749. S2CID 162341511.

- ^ "Prose Romance." The French Tradition and the Literature of Medieval England, by William Calin, University of Toronto Press, 1994, pp. 498–512. JSTOR. Accessed 1 Aug. 2020.

- ^ https://www.jstor.org/stable/27870563

- ^ Knight, Stephen (August 4, 2009). Merlin: Knowledge and Power Through the Ages. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0801443657 – via Google Books.

- ^ Sommer, H. Oskar (August 4, 1891). "Le Morte Darthur: Studies on the sources, with an introductory essay by Andrew Lang". D. Nutt – via Google Books.

- ^ "Morte d'Arthur." The Cambridge History of English Literature. A.W Ward, A.R Waller. Vol II. Cambridge: A UP, 1933. Print.

- ^ Gowans, Linda. "MALORY'S SOURCES – AND ARTHUR'S SISTERS – REVISITED." Arthurian Literature XXIX, pp. 121–142.

- ^ Radulescu, Raluca (2003). "Malory and Fifteenth-Century Political Ideas". Arthuriana. 13 (3): 36–51. doi:10.1353/art.2003.0042. JSTOR 27870541. S2CID 143784650.

- ^ https://www.jstor.org/stable/27869498

- ^ Withrington, John (1992). "Caxton, Malory, and the Roman War in the "Morte Darthur"". Studies in Philology. 89 (3): 350–366. JSTOR 4174429.

- ^ Wilson, Robert H. (1956). "Addenda on Malory's Minor Characters". The Journal of English and Germanic Philology. 55 (4): 563–587. JSTOR 27706826.

- ^ Jesmok, Janet (2004). "Comedic Preludes to Lancelot's 'Unhappy' Life in Malory's "Le Morte Darthur"". Arthuriana. 14 (4): 26–44. doi:10.1353/art.2004.0030. JSTOR 27870654. S2CID 161629997.

- ^ Field, P. J. C. (1993). "Malory and "Perlesvaus"". Medium Ævum. 62 (2): 259–269. doi:10.2307/43629557. JSTOR 43629557.

- ^ Wilson, Robert H. (1932). "Malory and the "Perlesvaus"". Modern Philology. 30 (1): 13–22. doi:10.1086/388002. JSTOR 434596. S2CID 161566473.

- ^ https://www.jstor.org/stable/27870196

- ^ Tucker, P. E. (1953). "The Place of the "Quest of the Holy Grail" in the "Morte Darthur"". The Modern Language Review. 48 (4): 391–397. doi:10.2307/3718652. JSTOR 3718652.

- ^ Naughton, Ryan. "Peace, Justice and Retinue-building in Malory's 'The Tale of Sir Gareth of Orkney'". Arthurian Literature. Vol. XXIX. pp. 143–160.[full citation needed]

- ^ Norris, Ralph (2008). Malory's Library: The Sources of the Morte Darthur. Vol. 71. Boydell & Brewer. ISBN 9781843841548. JSTOR 10.7722/j.ctt81sfd.

- ^ Hardman, P. (2004) "Malory and middle English verse romance: the case of 'Sir Tristrem'". In: Wheeler, B. (ed.) Arthurian Studies in Honour of P.J.C. Field. Arthurian Studies (57). D.S. Brewer, Cambridge, pp. 217-222. ISBN 9781843840138.

- ^ https://books.google.com/books?id=x0qEAgAAQBAJ&pg=PT36

- ^ https://books.google.com/books?id=TUi0c1alaJ8C&pg=PA136

- ^ https://www.jstor.org/stable/27870221

- ^ https://books.google.com/books?id=Bpvg6LuXCycC&pg=PA26

- ^ https://books.google.com/books?id=5zE3pcl1tjwC&pg=PA287

- ^ https://books.google.com/books?id=OAk7EAAAQBAJ&pg=PA211

- ^ https://www.jstor.org/stable/24643529

- ^ https://books.google.com/books?id=OAk7EAAAQBAJ&pg=PA48

- ^ Grimm, Kevin T. (1989). "Knightly Love and the Narrative Structure of Malory's Tale Seven". Arthurian Interpretations. 3 (2): 76–95. JSTOR 27868661.

- ^ "Lancelot and Guenevere".

- ^ https://www.jstor.org/stable/25095958

- ^ Donaldson, E. Talbot (1950). "Malory and the Stanzaic "Le Morte Arthur"". Studies in Philology. 47 (3): 460–472. JSTOR 4172937.

- ^ Wilson, Robert H. (1939). "Malory, the Stanzaic "Morte Arthur," and the "Mort Artu"". Modern Philology. 37 (2): 125–138. doi:10.1086/388421. JSTOR 434580. S2CID 162202568.

- ^ "Death of Arthur".

- ^ a b Lumiansky, R. M.; Baker, Herschel (November 11, 2016). Critical Approaches to Six Major English Works: From "Beowulf" Through "Paradise Lost". University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 9781512804140 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b Gaines, Barry (1974). "The Editions of Malory in the Early Nineteenth Century". The Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America. 68 (1): 1–17. doi:10.1086/pbsa.68.1.24302417. JSTOR 24302417. S2CID 180932930 – via JSTOR.

- ^ LYNCH, ANDREW (1999). ""Malory Moralisé": The Disarming of "Le Morte Darthur", 1800–1918". Arthuriana. 9 (4): 81–93. doi:10.1353/art.1999.0002. JSTOR 27869499. S2CID 161703303 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Bryan (1994), p. xii.

- ^ Bryan, ed. (1999), p. xviii.

- ^ "Morte D'Arthur: A Fragment | Robbins Library Digital Projects". d.lib.rochester.edu. Retrieved Oct 14, 2020.

- ^ Knowles, James (1862). The Legends of King Arthur and His Knights.

- ^ Malory, Thomas; Lanier, Sidney; Kappes, Alfred (16 October 1880). The Boy's King Arthur: Sir Thomas Malory's History of King Arthur and His Knights of the Round Table, Edited for Boys. Charles Scribner's Sons. OCLC 653360.

- ^ Lanier, Sidney (1 September 1950). King Arthur and His Knights of the Round Table. Grosset & Dunlap. ISBN 0448060167.

- ^ Dover Publications (1972). Beardsley's Illustrations for Le Morte Darthur, Publisher's note & back cover.

- ^ University, Bangor. "Stories of King Arthur and the Round Table". arthurian-studies.bangor.ac.uk. Retrieved 2018-07-26.

- ^ Boyle, Louis J. "T. H. WHITE'S REPRESENTATION OF MALORY'S CAMELOT." Arthurian Literature XXXIII.

- ^ Lupack, Barbara Tepa (2012). "The Girl's King Arthur: Retelling Tales". Arthuriana. 22 (3): 57–68. doi:10.1353/art.2012.0032. JSTOR 43485973. S2CID 162352846.

- ^ bookgroup.info: interview: Castle Freeman. Retrieved 2012-12-17.

- ^ A Chat With Castle Freeman, Jr. Retrieved 2012-12-17.

- ^ "The Death of King Arthur by Peter Ackroyd – review". The Guardian. June 23, 2011.

- ^ "Le morte D'Arthur by Chris Crawford – game". Erasmatazz. April 23, 2023.

External links

[edit]- Le Morte d'Arthur at Standard Ebooks

- Full Text of Volume One – at Project Gutenberg

- Full Text of Volume Two – at Project Gutenberg

Le Morte d'Arthur public domain audiobook at LibriVox

Le Morte d'Arthur public domain audiobook at LibriVox- Different copies of La Mort d'Arthur at the Internet Archive