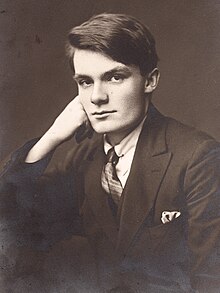

Francis Stuart

Francis Stuart | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 29 April 1902 Townsville, Queensland, Australia |

| Died | 2 February 2000 (aged 97) County Clare, Ireland |

| Occupation | Writer, lecturer |

| Nationality | Irish |

| Genre | Fiction, poetry, essays |

| Notable works |

|

| Spouse |

|

| Children |

|

Henry Francis Montgomery Stuart (29 April 1902 – 2 February 2000) was an Irish writer. He was awarded one of the highest artistic accolades in Ireland, being elected a Saoi of Aosdána, before his death in 2000.[1] His associations with the IRA and years in Nazi Germany led to a great deal of controversy.[2]

Early life

[edit]Francis Stuart was born in Townsville, Queensland, Australia[3][4] on 29 April 1902[5] to Irish Protestant parents, Henry Irwin Stuart and Elizabeth Barbara Isabel Montgomery. His father was an alcoholic and killed himself when Stuart was an infant. The widowed Elizabeth Stuart returned with her son to Ireland. The boy's childhood was divided between his home in Ireland and Rugby School in England, where he boarded.

In 1920, at age 17, he became a Catholic and married Iseult Gonne, Maud Gonne's daughter. Maud Gonne's companion, Mary Barry O'Delaney, stood as his godmother upon his conversion.[6] Aged 24 years, Iseult had had a romantic but unsettled life. Maud Gonne's estranged husband John MacBride was executed in 1916 for taking part in the Easter Rising. Iseult Gonne's father was the right-wing French politician Lucien Millevoye, with whom Maud Gonne had an affair between 1887 and 1899. Because of her complex family situation, Iseult was often passed off as Maud Gonne's niece in conservative circles in Ireland. Iseult grew up in Paris and London. She had been proposed to by W. B. Yeats in 1917 (he had also earlier proposed to her mother; Yeats was 50 at the time, Iseult 20). She also had a brief affair with Ezra Pound prior to meeting Stuart. Pound and Stuart both believed in the primacy of the artist over the masses and were subsequently drawn to fascism; Stuart to Nazi Germany and Pound to Fascist Italy.

IRA involvement

[edit]Gonne and Stuart had a baby daughter who died in infancy. Perhaps to recover from this tragedy, they travelled for a while in Europe but returned to Ireland as the Irish Civil War began. The couple were caught up on the anti-Treaty Irish Republican Army (IRA) side of this fight. Stuart was involved in gunrunning and was interned after a botched raid.

Literary career

[edit]After the establishment of the Irish Free State, Stuart participated in the literary life of Dublin and wrote poetry and novels. His novels were successful and his writing was publicly supported by Yeats. Yeats, however, seemed to have had mixed feelings for Stuart who was, after all, married to a woman he regarded almost as a daughter and, even, as a possible wife. In his poem "Why should not Old Men be Mad?" (1936) in which he lists what he regards as provocations to rage, he claims he has seen

- "A girl that knew all Dante once

- Live to bear children to a dunce"

The first of these lines is accepted as referring to Gonne and the second to Stuart (Elborn 1990).

Stuart and Gonne had three children, a daughter Dolores who died three months old, a son Ian and a daughter Katherine. Ian Stuart went on to become an artist and was married for a time to the sculptor Imogen Stuart and later to the Berlin-trained artist and jewellery designer Anna Stuart whom he first met in 1970. They gave Stuart three grandchildren; food entrepreneur Laragh, photographer Suki and sculptor Sophia.

Stuart's time with Gonne may not have been an entirely happy time; from the accounts given in his apparently autobiographical novels, both he and his wife struggled with personal demons, and their internal anguish poisoned their marriage. In her letters to close friend William Butler Yeats, Iseult Gonne's mother Maud Gonne characterizes Francis Stuart as being emotionally, financially, and physically abusive towards Iseult: "Stuart's conduct towards Iseult is shocking. While they were staying with me in Dublin he struck her & one day knocked her down. He threw her out of her own room with such violence that she fell on the landing half-dressed at the feet of Claud Chevasse who was staying in the house at the time."[7] Another time, neighbours reported seeing a fire in the couple's house: "They found Iseult in her dressing gown outside. Stuart had locked himself in her room from where the flames were coming. They could see him pouring petroleum. Finally, he opened the door -- he had been burning Iseult's clothes to punish her! Frequently he locked her up without food."[8]

Involvement with the Third Reich

[edit]It was also during the 1930s that Stuart became friendly with German Intelligence (Abwehr) agent Helmut Clissmann and his Irish wife Elizabeth. Clissmann was working for the German Academic Exchange Service and the Deutsche Akademie (DA). He was facilitating academic exchanges between Ireland and the Third Reich but also forming connections which might be of benefit to the Abwehr. Clissmann was also a representative of the Nazi Auslandorganisation (AO) – the Nazi Party's foreign organization – in pre-war Ireland.[citation needed]

Stuart was also friendly with the head of the German Foreign Office Legation in Dublin, Dr Eduard Hempel, largely as a result of Maud Gonne MacBride's rapport with him. By 1938 Stuart was seeking a way out of his marriage and the provincialism of Irish life. Iseult intervened with Clissmann to arrange for Stuart to travel to Germany to give a series of academic lectures in conjunction with the DA. Stuart travelled to Germany in April 1939 and was hosted by Professor Walter F. Schirmer, the senior member of the English faculty with the DA and Berlin University. He visited Munich, Hamburg, Bonn and Cologne. After his lecture tour, he accepted an appointment as a lecturer in English and Irish literature at Friedrich Wilhelm University to begin in 1940. At this time, under the Nuremberg Laws, the German academic system had barred Jews[relevant?].[citation needed]

In July 1939, Stuart returned home to Laragh and confirmed at the outbreak of war in September that he would still take the place in Berlin. When Stuart's plans for travelling to Germany were finalised, he received a visit from his brother-in-law, Seán MacBride, following the seizure of an IRA radio transmitter on 29 December 1939 which had been used to contact Germany. Stuart, MacBride, Seamus O'Donovan, and IRA Chief of Staff Stephen Hayes then met at O'Donovan's house. Stuart was told to take a message to Abwehr HQ in Berlin.[citation needed]

He arrived in Berlin in January 1940. Upon arrival, he delivered the IRA message and had some discussion with the Abwehr on conditions in Ireland and the fate of the IRA–Abwehr radio link. He also reactivated his acquaintance with Abwehr asset Helmut Clissmann who was acting as an advisor to SS Colonel Dr Edmund Veesenmayer. Through Clissmann, Stuart was introduced to Sonderführer Kurt Haller. Around August 1940, Stuart was asked by Haller if he would participate in Operation Dove and he agreed, although he was later dropped in favour of Frank Ryan. While Stuart maintained contact with Ryan until his death in June 1944, there's no record of any further involvement by him with the Abwehr.[citation needed]

Time in Berlin

[edit]Between March 1942 and January 1944 Stuart worked as part of the Redaktion-Irland (also sometimes referred to as Irland-Redaktion, "Editorial Ireland" in English) team, reading radio broadcasts containing Nazi ideology and propaganda which were aimed at and heard in Ireland. Before deciding to accept this job he discussed it with Frank Ryan, and they agreed that no anti-Semitic or anti-Soviet statements should be made. He was dropped from the Redaktion-Irland team in January 1944 because he objected to the anti-Soviet material that was presented to him and deemed essential by his supervisors. His passport was taken from him by the Gestapo after this event.[9]

In his radio broadcasts, he frequently spoke with admiration of Hitler and expressed the hope that a victorious Nazi Germany would help create a united Ireland. After the war, he maintained that he was not drawn to Germany by support for Nazism, but that he was fascinated by wartime Germany as a dark spectacle of the grotesque and as a celebration of destruction. Stuart described one such event at the Berlin Olympic stadium in June 1939 as: "A most amazing thing. Such a spectacle and organisation."[10]

Anti-semitism

[edit]Stuart is known to have read only one piece of what might be considered anti-semitic propaganda for Redaktion-Irland: his first. Whilst enthralled with the macabre spectacle of wartime Nazi Germany, he is also on record via his letters as deploring much of what he saw around him.[11]

However, Stuart did write the following in a 1924 Sinn Féin pamphlet (discovered by journalist Brendan Barrington, see Bibliography):

Austria, in 1921, had been ruined by the war, and was far, far poorer than Ireland is today, for besides having no money she was overburdened with innumerable debts. At that time Vienna was full of Jews, who controlled the banks and the factories and even a large part of the Government; the Austrians themselves seemed about to be driven out of their own city.[12]

Post World War II

[edit]In 1945 Stuart decided to return to Ireland with a former student, Gertrude Meissner; they were unable to do so and were arrested and detained by Allied troops. After they were released, Stuart and Meissner lived in Germany and then France and England. They married in 1954 after Iseult's death and in 1958 they returned to settle in Ireland. In 1971 Stuart published his best-known work, Black List Section H, an autobiographical fiction[13] documenting his life and distinguished by a queasy sensitivity to moral complexity and moral ambiguity.

In 1991 he made an extended appearance on British television: on 16 March he took part in an After Dark discussion called The Luck of The Irish? alongside J. P. Donleavy, David Norris, Emily O'Reilly, Paul Hill and others.[14]

In 1996 Stuart was elected a Saoi of Aosdána. This is a great honour in the Irish artistic and literary world and a highly influential Modern literature in Irish, the poet Máire Mhac an tSaoi, objected vehemently. Mhac an tSaoi referred to Stuart's actions during the Holocaust and accused him of being an anti-Semite. When it was put to a vote, Mhac an tSaoi was the only person to vote for the motion (there were 70 against, with 14 abstentions).[15] She resigned from Aosdána in protest, sacrificing a government stipend by doing so. While the Aosdána affair was ongoing, Irish Times columnist Kevin Myers attacked Stuart as a Nazi sympathiser; Stuart sued for libel and the case was settled out of court. The statement from the Irish Times read out in the High Court accepted "that Mr Stuart never expressed anti-Semitism in his writings or otherwise".[11]

For some years before his death he lived in County Clare with his partner Fionuala[who?] and in County Wicklow with his son Ian and daughter-in-law Anna in a house outside Laragh village.[citation needed] Stuart died of natural causes on 2 February 2000 at the age of 97 in County Clare.[5][16]

Works

[edit]- Fiction

- We Have Kept the Faith, Dublin 1923

- Women and God, London 1931

- Pigeon Irish, London 1932

- The Coloured Dome, London 1932

- Try the Sky, London 1933

- Glory, London 1933

- Things to Live For: Notes for an Autobiography, London 1934

- In Search of Love, London 1935

- The Angels of Pity, London 1935

- The White Hare, London 1936

- The Bridge, London 1937

- Julie, London 1938

- The Great Squire, London 1939

- Der Fall Casement, Hamburg 1940

- The Pillar of Cloud, London 1948

- Redemption, London 1949

- The Flowering Cross, London 1950

- Good Friday's Daughter, London 1952

- The Chariot, London 1953

- The Pilgrimage, London 1955

- Victors and Vanquished, London 1958

- Angels of Providence, London 1959

- Black List Section H, Southern Illinois University Press 1971 ISBN 0-14-006229-7)

- Memorial, London 1973

- A Hole in the Head, London 1977

- The High Consistory, London 1981

- We Have Kept the Faith: New and Selected Poems, Dublin 1982

- States of Mind, Dublin 1984

- Faillandia, Dublin 1985

- The Abandoned Snail Shell, Dublin 1987

- Night Pilot, Dublin 1988

- A Compendium of Lovers, Dublin 1990

- Arrow of Anguish, Dublin 1995

- King David Dances, Dublin 1996

- Pamphlets

- Nationality and Culture, Dublin 1924

- Mystics and Mysticism, Dublin 1929

- Racing for Pleasure and Profit in Ireland and Elsewhere, Dublin 1937

- Plays

- Men Crowd me Round, 1933

- Glory, 1936

- Strange Guests, 1940

- Flynn's Last Dive, 1962

- Who Fears to Speak, 1970

Bibliography

[edit]- Elborn, Geoffrey (1990). Francis Stuart: a Life. Dublin: Raven Arts Press. ISBN 978-1-85186-075-3.

- Hull, Mark (2003). Irish Secrets. Blackrock: Irish Academic Press. ISBN 0-7165-2756-1.

- McCartney, Anne (2000). Francis Stuart. Belfast: Institute of Irish Studies, Queen's University. ISBN 0-85389-768-9.

- Stephan, Enno (1963). Spies in Ireland. London: Macdonald.

- Barrington, Brendan, ed. (2001). The Wartime Broadcasts of Francis Stuart, 1942–1944. Dublin: Lilliput Press. ISBN 1-901866-54-8.

- Kiely, Kevin (2007). Francis Stuart: Artist and Outcast. Dublin: The Liffey Press. ISBN 978-1-905785-25-4.

- Lengthy interview conducted in 1998 by Naim Attallah

See also

[edit]- IRA Abwehr World War II – main article on IRA Nazi links

References

[edit]- ^ Irish Times, In honour of Francis Stuart? October 10, 1996

- ^ Obituary of Francis Stuart. The Guardian, 4 February 2000.

- ^ Francis Stuart Archived 5 October 2018 at the Wayback Machine Irish Paris. Retrieved: 29 August 2013.

- ^ Francis Stuart: Life Ricorso Irish writers database. Retrieved: 29 August 2013.

- ^ a b Obituary: Francis Stuart The Guardian, 4 February 2000.

- ^ Maume, Patrick (2009). "O'Delaney, Mary Barry". In McGuire, James; Quinn, James (eds.). Dictionary of Irish Biography. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- ^ MacBride White, Anna, ed. (1992). The Gonne-Yeats Letters 1893-1938. W W Norton. p. 404. ISBN 9780393034455.

- ^ MacBride White, Anna, ed. (1992). The Gonne-Yeats Letters 1893-1938. W W Norton. p. 404. ISBN 9780393034455.

- ^ David O'Donoghue: Hitler's Irish Voices – The Story of German Radio's Wartime Irish Service. Beyond the Pale, Dublin 1998 ISBN 1-900960-04-4

- ^ Hull, p.310

- ^ a b Cronin, Anthony (27 June 1999). "Healing the Wounds of Francis Stuart". The Irish Independent. p. 1.

- ^ Colm Tóibín, "Issues of Truth and Invention" (Part II) Archived 19 December 2006 at the Wayback Machine, London Review of Books, 1 September 2000, on colmtoibin.com

- ^ Welch (ed.), Robert (1996). The Oxford Companion to Irish Literature. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0198661584.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ See List of After Dark editions#Series 4

- ^ The Irish Times, 27 November 1997

- ^ Francis Stuart dies RTÉ News, 2 February 2000.

External links

[edit]- Aosdána short biography Archived 5 May 2005 at the Wayback Machine

- RTÉ short obituary

- The Guardian obituary

- Francis Stuart Papers, 1932–1971 Archived 25 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine at Southern Illinois University Carbondale, Special Collections Research Center

- Colm Tóibín, "Issues of Truth and Invention" Archived 28 April 2005 at the Wayback Machine – Essay on Francis Stuart

- Amanda French, " A Strangely Useless Thing': Iseult Gonne and Yeats," Yeats Eliot Review: A Journal of Criticism and Scholarship 19.2 (2002): 13–24. (pdf)

- 1902 births

- 2000 deaths

- Saoithe

- Australian Roman Catholics

- Converts to Roman Catholicism from Evangelicalism

- Irish collaborators with Nazi Germany

- People of the Irish Civil War (Anti-Treaty side)

- Irish Roman Catholic writers

- Irish expatriates in Germany

- People educated at Rugby School

- People from Townsville

- Australian people of Irish descent

- Protestant Irish nationalists

- 20th-century Irish novelists

- 20th-century Irish male writers

- Irish male novelists

- Radio in Nazi Germany

- Nazi propaganda radio

- Irish radio presenters

- Australian radio presenters

- Claddagh Records artists