Yojimbo

| Yojimbo | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

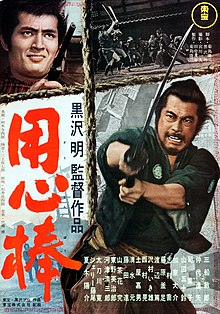

Theatrical release poster | |||||

| Japanese name | |||||

| Kanji | 用心棒 | ||||

| Literal meaning | Bodyguard | ||||

| |||||

| Directed by | Akira Kurosawa | ||||

| Screenplay by |

| ||||

| Story by | Akira Kurosawa | ||||

| Produced by |

| ||||

| Starring | |||||

| Cinematography | Kazuo Miyagawa[1] | ||||

| Edited by | Akira Kurosawa[1] | ||||

| Music by | Masaru Sato[1] | ||||

Production companies |

| ||||

| Distributed by | Toho[1] | ||||

Release date |

| ||||

Running time | 110 minutes[1] | ||||

| Country | Japan | ||||

| Language | Japanese | ||||

| Budget | ¥90.87 million (US$631,000)[2] | ||||

| Box office | $2.5 million (est.) | ||||

Yojimbo (Japanese: 用心棒, Hepburn: Yōjinbō, lit. Bodyguard) is a 1961 Japanese samurai film directed by Akira Kurosawa, who also co-wrote the screenplay and was one of the producers. The film stars Toshiro Mifune, Tatsuya Nakadai, Yoko Tsukasa, Isuzu Yamada, Daisuke Katō, Takashi Shimura, Kamatari Fujiwara, and Atsushi Watanabe. In the film, a rōnin arrives in a small town where competing crime lords fight for supremacy. The two bosses each try to hire the newcomer as a bodyguard.

Based on the success of Yojimbo, Kurosawa's next film, Sanjuro (1962), was altered to incorporate the lead character of this film.[3][4] In both films, the character wears a rather dilapidated dark kimono bearing the same family mon.[a]

The film was released and produced by Toho on April 25, 1961. Yojimbo received highly positive reviews, and, over the years, became widely regarded as one of the best films by Kurosawa and one of the greatest films ever made. The film grossed an estimated US$2.5 million worldwide with a budget of ¥90.87 million ($631,000). It was unofficially remade by Sergio Leone as the Spaghetti Western film A Fistful of Dollars (1964),[5] leading to a lawsuit by Toho.

Plot

[edit]In 1860, during the final years of the Edo period,[b] a rōnin wanders through a desolate countryside. Coming to a fork in the road, he chooses which path to take at random.

Stopping at a farmhouse for water, the rōnin overhears an elderly couple lamenting that their only son has run off to join the "gamblers" in a nearby town, which is overrun with criminals and contested by two rival yakuza gangs.

In the town, the rōnin stops at a small izakaya (tavern). The owner Gonji advises him to leave. Gonji tells the rōnin that the two warring bosses, Ushitora and Seibei, are fighting over the lucrative gambling trade run by Seibei. Ushitora had been Seibei's right-hand man until Seibei decided that his successor would be his son Yoichiro, a useless youth. The town's mayor, a silk merchant named Tazaemon, had long been in Seibei's pocket, so Ushitora aligned himself with the local sake brewer, Tokuemon, proclaiming him the new mayor.

After sizing up the situation and recognizing that no one in town cares about ending the violence, the stranger says he intends to stay, as the town would be better off with both sides dead. He convinces the weaker Seibei to hire his services by effortlessly killing three of Ushitora's men. When asked his name, he sees a mulberry field and states his name is Kuwabatake ("mulberry field") Sanjuro ("thirty-years-old") (桑畑三十郎).[c]

Seibei decides that with the ronin's help, it is time to deal with Ushitora. Sanjuro eavesdrops on Seibei's wife, who orders Yoichiro to prove himself by killing the ronin after the upcoming raid, saving them from having to pay him. Sanjuro leads the attack on Ushitora's faction, but then "resigns" over Seibei's treachery, expecting both sides to massacre each other. His plan is foiled due to the unexpected arrival of a bugyō (a government official), which prompts both Seibei and Ushitora to make a bloodless retreat.

The bugyō leaves soon after to investigate the assassination of a fellow official in another town. Overhearing the assassins discussing the hit in Gonji's tavern, Sanjuro later captures them and sells them to Seibei. Then he comes to Ushitora and tells him Seibei's men caught the assassins. Alarmed, Ushitora generously rewards Sanjuro for his "help," and kidnaps Yoichiro to exchange for the two assassins. At the swap, Ushitora's brother Unosuke kills the assassins with a pistol.

Anticipating this, Seibei reveals he had ordered the kidnapping of Tokuemon’s mistress. The next morning, she is exchanged for Yoichiro. Sanjuro learns that the mistress, Nui, is a local farmer's wife. After he sold her to Ushitora to settle a gambling debt, Ushitora gave her to Tokuemon as chattel to gain his support. After tricking Ushitora into revealing where Nui is held, Sanjuro kills the guards and reunites the woman with her husband and son, ordering them to leave town immediately. He comes to Ushitora and informs him that Seibei is responsible for killing his men.

The gang war escalates, with Ushitora burning down Tazaemon's silk warehouse and Seibei retaliating by trashing Tokuemon's brewery. After some time, Unosuke becomes suspicious of Sanjuro and the circumstances surrounding Nui's escape, eventually uncovering evidence of the ronin's betrayal. Sanjuro is severely beaten and imprisoned by Ushitora's thugs, who torture him to find out Nui's whereabouts.

When Ushitora decides to eliminate Seibei once and for all, Sanjuro escapes. Smuggled out of town in a coffin by Gonji, Sanjuro witnesses the brutal end of Seibei and his family. Sanjuro recuperates in a small temple near a cemetery.

Upon learning Gonji has been captured by Ushitora, he returns to town. In a final confrontation with Ushitora, Unosuke, and their gang, Sanjuro dispatches them. He spares a terrified young man (the son of the elderly couple from the opening of the film) and sends him back to his parents. As Sanjuro surveys the damage, a now insane Tazaemon comes out of his home in a samurai outfit and stabs Tokuemon to death. Sanjuro frees Gonji, proclaims that the town will be quiet from then on, and departs.

Cast

[edit]- Toshiro Mifune as "Kuwabatake Sanjuro" (桑畑 三十郎), a wandering ronin and master swordsman drawn into a gang war.

- Eijirō Tōno as Gonji (権爺), the izakaya (tavern) owner and the ronin's ally and confidant.

- Tatsuya Nakadai as Unosuke (卯之助), a gun-toting gangster and younger brother to both Ushitora and Inokichi.

- Seizaburo Kawazu as Seibei (清兵衛), the original boss of the town's underworld. He operates out of a brothel.

- Kyū Sazanka as Ushitora (丑寅), the other gang leader in town. He was originally Seibei's lieutenant but broke ranks to start his own syndicate in a succession dispute.

- Isuzu Yamada as Orin (おりん), the wife of Seibei and the brains behind her husband's criminal operations.

- Daisuke Katō as Inokichi (亥之吉), younger brother of Ushitora and older brother to Unosuke. He is a strong fighter but is very dim-witted and easily fooled.

- Takashi Shimura as Tokuemon (徳右衛門), a sake brewer who claims to be the new mayor.

- Hiroshi Tachikawa as Yoichiro (倅与一郎), the timid son of Seibei and Orin who shows little inclination to take over his father's gang.

- Yosuke Natsuki as Farmer's Son, a young man seen running away from home at the beginning of the film who joins Ushitora's gang.

- Kamatari Fujiwara as Tazaemon (多左衛門), the town mayor and silk merchant who is going insane from fear.

- Ikio Sawamura as Hansuke (半助), the town constable who is completely corrupt and concerned only with keeping himself alive.

- Atsushi Watanabe as the town's coffin maker, who is profiting heavily from the gang war but ultimately chooses to help Sanjuro and Gonji put an end to it.

- Susumu Fujita as Honma (本間), Seibei's "master swordsman" who deserts his employer before a battle with Ushitora's men, allowing Sanjuro to take his place.

- Sachio Sakai as Ashigaru

- Yoko Tsukasa as Nui (ぬい), the wife of Kohei. She was taken prisoner by Tokuemon because of her beauty after her husband could not pay back his gambling debts.

- Yoshio Tsuchiya as Kohei (小平), the husband of Nui who lost all of his money gambling and frequently gets beaten for trying to visit his wife.

- Taku Iyaku as Kannuki (かんぬき), Ushitora's acromegalic enforcer.

Production

[edit]Writing

[edit]Kurosawa stated that a major source for the plot was the 1942 film noir classic The Glass Key, an adaptation of Dashiell Hammett's 1931 novel of the same name. It has been noted that the overall plot of Yojimbo is closer to that of another Hammett novel, Red Harvest (1929).[6] Kurosawa scholar David Desser, and film critic Manny Farber claim that Red Harvest was the inspiration for the film; however, Donald Richie and other scholars believe the similarities are coincidental.[7]

When asked his name, the samurai calls himself "Kuwabatake Sanjuro", which he seems to make up while looking at a mulberry field by the town. Thus, the character can be viewed as an early example of the "Man with No Name" (other examples of which appear in several earlier novels, including Dashiell Hammett's Red Harvest).[8]

Casting

[edit]Many of the actors in Yojimbo worked with Kurosawa before and after, especially Toshiro Mifune, Takashi Shimura and Tatsuya Nakadai.[9]

Filming

[edit]After Kurosawa scolded Mifune for arriving late to the set one morning; Mifune made it a point to be ready on set at 6:00 AM every day in full makeup and costume for the rest of the film's shooting schedule.[10]

This was the second film where director Akira Kurosawa worked with cinematographer Kazuo Miyagawa (the first being Rashomon in 1950).[11] The sword instruction and choreography for the film were done by Yoshio Sugino of the Tenshin Shōden Katori Shintō-ryū and Ryū Kuze.[12]

Music

[edit]The soundtrack for the film has received positive reviews. Michael Wood writing retrospectively for the London Review of Books found the film's soundtrack by Masaru Sato as effective in its 'jaunty and jangling' approach stating:[13]

The film is full of music, for instance, a loud, witty soundtrack by Masaru Sato, who said his main influence was Henry Mancini. It doesn’t sound like Breakfast at Tiffany’s, though, or Days of Wine and Roses. The blaring Latin sound of Touch of Evil comes closer, but actually you wouldn’t think of Mancini if you hadn’t been told. Sato’s effect has lots of drums, mixes traditional Japanese flutes and other instruments with American big band noises, and feels jaunty and jangling throughout, discreetly off, as if half the band was playing in the wrong key. It’s distracting at first, then you realise it’s not decoration, it’s commentary. It’s a companion to Sanjuro, the sound of his mind, discordant and undefeated and unserious, even when he’s grubby and silent and apparently solemn.[13]

Release

[edit]Yojimbo was released in Japan on 25 April 1961.[1] The film was released by Seneca International in both a subtitled and dubbed format in the United States in September 1961.[1]

Box office

[edit]Yojimbo was Japan's fourth highest-grossing film of 1961, earning a distribution rental income of ¥351 million.[14] This was equivalent to estimated box office gross receipts of approximately ¥659 million[15] ($1.83 million).[16]

Overseas, the film had a September 1961 release in North America, but the box office income of this release is currently unknown.[17] At the 2002 Kurosawa & Mifune Festival in the United States, the film grossed $561,692.[18] In South Korea, a 2012 re-release grossed ₩1.566 million[19] ($1,390).

In Europe, a January 1991 limited French re-release sold 14,178 tickets,[20] equivalent to an estimated gross revenue of approximately €63,801[21] ($87,934).[22] Other limited European re-releases sold 3,392 tickets between 2000 and 2018,[23] equivalent to an estimated gross revenue of at least €18,995[21] ($27,938). This adds up to an estimated $678,950 grossed overseas, and an estimated $2,508,950 grossed worldwide.

Adjusted for ticket price inflation, at 2012 Japanese ticket prices, its Japanese gross receipts are equivalent to an estimated ¥9.75 billion[15] ($122 million), or $162 million adjusted for inflation in 2023. The overseas gross revenue of North American and European re-releases since 1991 are equivalent to approximately $1.5 million adjusted for inflation, adding up to an estimated inflation-adjusted total gross of over $137 million worldwide.

Critical response

[edit]Yojimbo was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Costume Design at the 34th Academy Awards. Toshiro Mifune won the Volpi Cup for Best Actor at the 22nd Venice Film Festival.

A 1968 screening in the planned community of Columbia, Maryland was considered too violent for viewers, causing the hosts to hide in the bathroom to avoid the audience.[24]

In a retrospective look at the film Michael Wood writing for the London Review of Books found the film to span several genres and compared it to other western and samurai films from the 1950s, 60s, and 70s, such as Seven Samurai, A Fistful of Dollars, High Noon, The Outlaw Josey Wales, and Rashomon, stating, "(The film contains) comedy, satire, folk tale, action movie, Western, samurai film, and something like a musical without songs. As everyone says, this work is not as deep as Rashomon or as immediately memorable as Seven Samurai. But it is funnier than any Western from either side of the world, and its only competition, in a bleaker mode, would be Clint Eastwood’s The Outlaw Josey Wales (1976)."[13] In 2009 the film was voted at No. 23 on the list of The Greatest Japanese Films of All Time by Japanese film magazine Kinema Junpo.[25] Yojimbo was also ranked at #95 in Empire magazine's list of the 500 Greatest Films of All Time.[26]

Sequel

[edit]In 1962, Kurosawa directed Sanjuro, originally intended to be a straight adaptation of Shūgorō Yamamoto's short story Hibi Heian (日日平安, lit. "Peaceful Days"), but was reworked to include Mifune and his character following the success of Yojimbo.[3]

In both films, he takes his surname from the plants he happens to be looking at when asked his name: in Yojimbo it is the mulberry trees that feed the town's silkworms, and in Sanjuro it is camellia bushes used to make tea.[27]

Legacy

[edit]Both in Japan and in the West, Yojimbo has influenced various forms of entertainment, starting with a remake as A Fistful of Dollars (1964), a Spaghetti Western directed by Sergio Leone and starring Clint Eastwood in his first appearance as the Man with No Name.[28] That film was followed by two prequels. The three films are collectively known as the Dollars Trilogy. Leone and his production company failed to secure the remake rights to Kurosawa's film, resulting in a lawsuit that delayed Fistful's release in North America for three years. It was settled out of court for an undisclosed agreement before the U.S. release.[29] In Yojimbo, the protagonist defeats a man who carries a gun, while he carries only a knife and a sword; in the equivalent scene in A Fistful of Dollars, Eastwood's pistol-wielding character survives being shot by a rifle by hiding an iron plate under his clothes to serve as a shield against bullets.[citation needed]

A second, looser Spaghetti Western adaptation, Django (1966), was directed by Sergio Corbucci and featured Franco Nero in the title role. Known for its high level (at the time of its release) of graphic violence, the film's character and title were referenced in two official films (a sequel and prequel) and over thirty unofficial ones.[30][31][32]

The film Zatoichi Meets Yojimbo (1970) features Mifune as a somewhat similar character. It is the twentieth of a series of movies featuring the blind swordsman Zatoichi. Although Mifune is clearly not playing the same "Yojimbo"[33] as he did in the two Kurosawa films (his name is Sasa Daisaku 佐々大作, and his personality and background are different in many key respects), the movie's title and some of its content do intend to suggest the image of the two iconic jidaigeki characters confronting each other.[citation needed]

Incident at Blood Pass (1970), made the same year, stars Mifune as a ronin who looks and acts even more similarly to Sanjuro and is referred to simply as "Yojimbo"[33] throughout the film, but whose name is Shinogi Tōzaburō.[34] As was the case with Sanjuro, this character's surname of Shinogi (鎬) is not an actual proper family name, but rather a term that means "ridges on a blade".[citation needed]

Mifune's character became the model for John Belushi's Samurai Futaba character on Saturday Night Live.[35]

Star Wars Episode IV: A New Hope (1977) pays narrative and visual homage to Yojimbo during the cantina scene early in the film. When Luke Skywalker approaches the bar, he is accosted by Ponda Baba and Doctor Evazan, who like the gamblers confronting Sanjuro inform him of serious criminal penalties they have received elsewhere (death sentences in 12 jurisdictions) to intimidate him. Obi-Wan Kenobi intervenes just as they threaten Luke's life, and after he briefly wields his lightsaber the camera likewise shows a severed forearm on the floor to demonstrate the character's prowess with the weapon.[36]

Similarly, Star Wars: The Last Jedi (2017) was also heavily influenced by Yojimbo. In the film's third act, Luke Skywalker's attire is visually reminiscent of that of Sanjuro's, both characters are also framed in Wide shot and are portrayed as lone heroes with both having to deal with a larger threat by themselves, Sanjuro confronts Ushitora, Unosuke, and their gang while Luke confronts the entire First Order. During his showdown with Kylo Ren, Luke's last line is "See you around, kid", which recalls Sanjuro's last line, "Aba yo", meaning "See you around".[37]

James Bond screenwriter Michael G. Wilson compared the writing of Licence to Kill to Akira Kurosawa's Yojimbo, where a samurai "without any attacking of the villain or its cohorts, only sowing the seeds of distrust, he manages to have the villain bring himself down".[38]

The Warrior and the Sorceress (1984) is another retelling of the story, this one in a fantasy world.[39]

Last Man Standing (1996) is a Prohibition-era action film directed by Walter Hill and starring Bruce Willis. It is an official remake of Yojimbo with both Kikushima and Kurosawa specifically listed in this movie's credits as having provided the original story.[40]

At the closing of Episode XXIII (S02E10) of the animated series Samurai Jack (2002; S02), a triumphant Jack walks off alone in a scene (and accompanied by music) influenced by the closing scene and music of Yojimbo. In Episode XXVI (S02E13), Jack confronts a gang who destroyed his sandals, using Clint Eastwood's lines from A Fistful of Dollars, but substituting "footwear" for "mule". The influence of Yojimbo in particular (and Kurosawa films in general) on the animated series has been noted by Matthew Millheiser at DVDtalk.[41]

Inferno (1999) (aka Desert Heat) is a remake and an homage to Yojimbo.[citation needed]

Stan Sakai's comic-book series Usagi Yojimbo (since 1984) is inspired by Kurosawa's movies.[citation needed]

References

[edit]- Notes

- ^ The mon Mifune's character wears in both films is the Maruni Kenkatabami (丸に剣片喰), which is the mon of director Akira Kurosawa.

- ^ On screen text at about 00:02:15

- ^ 三十郎 Sanjuro is a proper given name (and therefore could very well be the rōnin's true name), but it can also be interpreted as meaning "thirty-years-old".

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i Galbraith IV 1996, p. 448.

- ^ Jiji Press 1962, p. 211.

- ^ a b Richie, Donald. The films of Akira Kurosawa. p. 156.

- ^ Yoshinari Okamoto (director) (2002). Kurosawa Akira: Tsukuru to iu koto wa subarashii [Akira Kurosawa: It is Wonderful to Create] (in Japanese).

- ^ "Yojimbo, A Fistful of Dollars and the curious case of Kurosawa vs Leone". Firstpost. 2017-12-18. Retrieved 2020-07-17.

- ^ Desser, David (1983). "Towards a Structural Analysis of the Postwar Samurai Film". Quarterly Review of Film Studies (Print). 8 (1). Redgrave Publishing Company: 33. doi:10.1080/10509208309361143. ISSN 0146-0013.

- ^ Barra, Allen (2005). "From Red Harvest to Deadwood". Salon. Archived from the original on 2008-12-05. Retrieved 2006-06-22.

- ^ Dashiell Hammett (1992). Red Harvest. Knopf Doubleday Publishing. ISBN 0-679-72261-0.

- ^ "Kurosawa's Actors". kurosawamovies.com. Retrieved 18 November 2016.

- ^ Peary, Gerald (June 6, 1986). "Toshiro Mifune". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved 2013-04-30.

One day Kurosawa said, 'I won't mention names, but the actors are late.' I said. 'What are you talking about? I'm the actor.' Every day after that, when Kurosawa arrived, I would be there already, in costume and makeup from 6 a.m. I showed him.

- ^ Bergan, Ronald (20 August 1999). "Kazuo Miyagawa The innovative Japanese cinematographer whose reputation was made by Rashomon". theguardian.com. Retrieved 18 November 2016.

- ^ Li, Christopher (18 April 2015). "Interview with Yoshio Sugino of Katori Shinto-ryu, 1961". aikidosangenkai.org. Retrieved 18 November 2016.

- ^ a b c London Review of Books, Vol. 29 No. 4 · 22 February 2007, page 17, At the Movies, Michael Wood, Yojimbo directed by Akira Kurosawa.[1]

- ^ Kinema Junpo 2012, p. 180.

- ^ a b "Statistics of Film Industry in Japan". Eiren. Motion Picture Producers Association of Japan. Retrieved 20 June 2020.

- ^ "Official exchange rate (LCU per US$, period average) - Japan". World Bank. 1961. Retrieved 20 June 2020.

- ^ "Yojimbo". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 20 June 2020.

- ^ "Kurosawa & Mifune Festival". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 20 June 2020.

- ^ "영화정보" [Movie Information]. KOFIC (in Korean). Korean Film Council. Retrieved 26 August 2019.

- ^ "Yojimbo (1961)". JP's Box-Office (in French). Retrieved 20 June 2020.

- ^ a b "Cinema market". Cinema, TV and radio in the EU: Statistics on audiovisual services (Data 1980-2002) (2003 ed.). Office for Official Publications of the European Communities. 2003. pp. 31–64 (61). ISBN 92-894-5709-0. ISSN 1725-4515. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ^ "Historical currency converter with official exchange rates (EUR)". 31 January 1991. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- ^ "Film #16103: Yojimbo". Lumiere. European Audiovisual Observatory. Retrieved 20 June 2020.

- ^ Joseph Rocco Mitchell, David L. Stebenne. New City Upon a Hill. p. 116.

- ^ "Greatest Japanese films by magazine Kinema Junpo (2009 version)". Archived from the original on July 11, 2012. Retrieved 2011-12-26.

- ^ "The 500 Greatest Movies Of All Time". Empire. Bauer Media Group. Archived from the original on 2011-08-14. Retrieved August 17, 2011.

- ^ Conrad 2022.

- ^ Curti 2016, pp. 25–26.

- ^ Galbraith IV 2002, p. 312.

- ^ Marco Giusti, Dizionario del western all'italiana, 1st ed. Milan, Mondadori, August 2007. ISBN 978-88-04-57277-0.

- ^ Django (Django: The One and Only) (DVD). Los Angeles, California: Blue Underground. 1966.

- ^ Cox, Alex (2009-09-01). 10,000 Ways to Die: A Director's Take on the Spaghetti Western. Oldcastle Books. ISBN 978-1842433041.

- ^ a b "archive.animeigo.com liner notes". Retrieved 2018-08-18.

- ^ "待ち伏せ". Eiga.com (in Japanese). Kakaku.com. Archived from the original on 2021-09-09. Retrieved 2018-08-17.

- ^ Barra, Allen (2010-08-17). "That Nameless Stranger, Half a Century Later". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 2012-01-10.

- ^ "Star Wars Episodes IV-VI: Influences". Spark Notes. Retrieved 2022-04-26.

- ^ "HOW AKIRA KUROSAWA INSPIRED STAR WARS & THE LAST JEDI 40 YEARS APART". 2018-01-25. Retrieved 2022-07-28.

- ^ John Cork (1999). Audio commentary (DVD). Licence to Kill: Ultimate Edition: MGM.

- ^ DVD Talk - Roger Corman's Cult Classics Double Feature: The Warrior and the Sorceress/Barbarian Queen

- ^ "A Comparison of 'Yojimbo', 'A Fistful of Dollars' and 'Last Man Standing'". 30 September 2003. Retrieved 2018-08-19.

- ^ "Samurai Jack: Season 1 : DVD Talk Review of the DVD Video". Dvdtalk.com. Retrieved 2014-04-08.

Sources

[edit]- Conrad, David A. (2022). Akira Kurosawa and Modern Japan. McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-1476686745.

- Curti, Roberto (2016). Tonino Valerii: The Films. McFarland. ISBN 978-1476626185.

- Galbraith IV, Stuart (2002). The Emperor and the Wolf: The Lives and Films of Akira Kurosawa and Toshiro Mifune. Faber and Faber, Inc. p. 312. ISBN 978-0-571-19982-2.

- Galbraith IV, Stuart (1996). The Japanese Filmography: 1900 through 1994. McFarland. ISBN 0-7864-0032-3.

- Movie Yearbook: 1962 Edition (in Japanese). Jiji Press. 1962.

- "Kinema Junpo Best Ten 85th Complete History 1924-2011". Kinema Junpo (in Japanese). Kinema Junposha. May 17, 2012. ISBN 9784873767550.

External links

[edit]- Yojimbo at IMDb

- Yojimbo at AllMovie

- Yojimbo at Box Office Mojo

- Yojimbo at Rotten Tomatoes

- West Meets East an essay by Alexander Sesonske at the Criterion Collection

- A Comparison of Yojimbo, A Fistful of Dollars and Last Man Standing

- Yojimbo (in Japanese) at the Japanese Movie Database

- 1961 films

- 1960s Japanese-language films

- 1960s action drama films

- Japanese black-and-white films

- Japanese action drama films

- Jidaigeki films

- Films directed by Akira Kurosawa

- 1960s samurai films

- Films set in the 1860s

- Toho films

- Films with screenplays by Akira Kurosawa

- Films with screenplays by Ryuzo Kikushima

- Films produced by Ryūzō Kikushima

- Films produced by Tomoyuki Tanaka

- Films scored by Masaru Sato

- 1961 drama films

- 1960s Japanese films

- Japanese action adventure films

- Japanese adventure drama films

- Japanese historical adventure films

- Japanese historical drama films