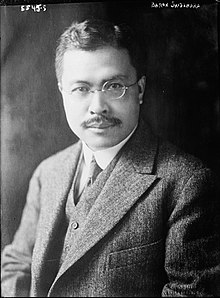

Kijūrō Shidehara

Kijūrō Shidehara | |

|---|---|

| 幣原 喜重郎 | |

| |

| Prime Minister of Japan | |

| In office 9 October 1945 – 22 May 1946 | |

| Monarch | Hirohito |

| Governor | Douglas MacArthur |

| Preceded by | Naruhiko Higashikuni |

| Succeeded by | Shigeru Yoshida |

| In office 14 November 1930 – 10 March 1931 Acting | |

| Monarch | Hirohito |

| Preceded by | Osachi Hamaguchi |

| Succeeded by | Osachi Hamaguchi |

| Speaker of the House of Representatives | |

| In office 11 February 1949 – 10 March 1951 | |

| Monarch | Hirohito |

| Preceded by | Komakichi Matsuoka |

| Succeeded by | Joji Hayashi |

| Member of the House of Representatives for Osaka 3rd District | |

| In office 26 April 1947 – 10 March 1951 | |

| Member of the House of Peers | |

| In office 29 January 1926 – 25 April 1947 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 13 September 1872 Sakai, Nara Prefecture, Empire of Japan (nowadays Kadoma, Osaka Prefecture, Japan) |

| Died | 10 March 1951 (aged 78) Tokyo, Allied-occupied Japan |

| Political party | Independent |

| Alma mater | Tokyo Imperial University |

| Signature |  |

Baron Kijūrō Shidehara (幣原 喜重郎, Shidehara Kijūrō, 13 September 1872 – 10 March 1951) was a Japanese diplomat and politician, who was prime minister of Japan from 1945 to 1946 and a leading proponent of pacifism in Japan before and after World War II. He was the last Japanese Prime Minister who was a member of the peerage (kazoku). His wife, Masako, was the fourth daughter of Iwasaki Yatarō, founder of the Mitsubishi zaibatsu.

Early life and career

[edit]Shidehara was born on 13 September 1872, in Kadoma, Osaka, into a wealthy farming family (gōnō).[1] His brother Taira was the first president of Taihoku Imperial University. Shidehara attended Tokyo Imperial University, and graduated from the Faculty of Law, where he had studied under Hozumi Nobushige. After graduation, he found a position within the Foreign Ministry and was sent as a consul to Chemulpo in Korea in 1896.

In 1903 Shidehara married Masako Iwasaki, who came from the family that founded the Mitsubishi zaibatsu.[2] This made him the brother-in-law of Katō Takaaki, who had also been prime minister.[3]

He subsequently served in the Japanese embassy in London, Antwerp, and Washington D.C., and as ambassador to the Netherlands, returning to Japan in 1915.

In 1915, Shidehara was appointed Vice Minister of Foreign Affairs and continued in this position during five consecutive administrations. In 1919, he was named ambassador to the United States and was Japan's leading negotiator during the Washington Naval Conference. His negotiations led to the return of Jiaozhou Bay concession to China. However, while he was ambassador, the United States enacted discriminatory immigration laws against Japanese, which created much ill will in Japan.

Shidehara was elevated to the title of danshaku (baron) under the kazoku peerage system in 1920, and appointed to a seat in the House of Peers in 1925.

-

From left to right: Robert Woods Bliss, Robert Coontz, Kanji Kato, Kunishige Tanaka [ja], Andre Brewster at the Washington Conference on 24 October 1921.

-

Left to right; Baron Kijuro Shidehara, Admiral Katō Tomosaburō, Prince Iesato Tokugawa on 3 November 1921, to attend the Washington Naval Conference.

First term as Foreign Minister

[edit]In 1924, Shidehara became Minister of Foreign Affairs in the cabinet of Prime Minister Katō Takaaki and continued in this post under Prime Ministers Wakatsuki Reijirō and Osachi Hamaguchi. Despite growing Japanese militarism, Shidehara attempted to maintain a non-interventionist policy toward China, and good relations with Great Britain and the United States, which he admired. In his initial speech to the Diet of Japan, he pledged to uphold the principles of the League of Nations.

The term "Shidehara diplomacy" came to describe Japan's liberal foreign policy during the 1920s. In October 1925, he surprised other delegates to the Beijing Customs Conference in pushing for agreement to China's demands for tariff autonomy. In March 1927, during the Nanking Incident, he refused to agree to an ultimatum prepared by other foreign powers threatening retaliation for the actions of Chiang Kai-shek's Kuomintang troops for their attacks on foreign consulates and settlements.

Disgruntlement by the military over Shidehara's China policies was one of the factors that led to the collapse of the administration of Prime Minister Wakatsuki in April 1927. During his diplomatic career, Shidehara was known for his excellent command of the English language. At one press conference, an American reporter was confused regarding the pronunciation of Shidehara's name: the foreign minister replied, "I'm Hi(he)-dehara, and my wife is Shi(she)-dehara." Because his wife was a Quaker, Shidehara was rumoured to be one too.

Second term as Foreign Minister

[edit]

Shidehara returned as Foreign Minister in 1929, and immediately resumed the non-interventionist policy in China, attempting to restore good relations with Chiang Kai-shek's government now based in Nanjing. This policy was assailed by military interests who believed it was weakening the country, especially after the conclusion of the London Naval Conference 1930, which precipitated a major political crisis.

When Prime Minister Osachi Hamaguchi was seriously wounded in an assassination attempt, Shidehara served as interim prime minister until March 1931. In September 1931, the Kwantung Army invaded and occupied Manchuria in the Manchurian Incident without prior authorization from the central government. This effectively ended the non-interventionist policy towards China, and Shidehara's career as foreign minister.

In October 1931, Shidehara was featured on the cover of Time with the caption "Japan's Man of Peace and War".[4]

Shidehara remained in government as a member of the House of Peers from 1931 to 1945. He maintained a low profile through the end of World War II.

As Prime Minister

[edit]

At the time of Japan's surrender in 1945, Shidehara was in semi-retirement. However, largely because of his pro-American reputation, he was appointed to serve as Japan's first post-war prime minister, from 9 October 1945 to 22 May 1946. Along with the post of prime minister, Shidehara became president of the Progressive Party (Shinpo-tō).

Shidehara's cabinet appointed a non-official committee to look into the question of drafting a new constitution for Japan in line with General Douglas MacArthur's policy directives, but the draft was vetoed by the occupation authorities. According to MacArthur and others, it was Shidehara who originally proposed the inclusion of Article 9 of the Constitution of Japan, a provision which limits Japan's ability to wage war. Shidehara, in his memoirs Gaikō gojūnen ("Fifty-years Diplomacy", 1951) also admitted to his authorship, and described how the idea came to him on a train ride to Tokyo. Already when he was ambassador in Washington, he had become acquainted with the idea of 'outlawing war' in international and constitutional law. One of his famous sayings was: "Let us create a world without war (sensō naki sekai) together with the world-humanity (sekai jinrui).”

However, his supposed conservative economic policies and family ties to the Mitsubishi interests made him unpopular with the leftist movement.

The Shidehara cabinet resigned following Japan's first postwar election, when the Liberal Party of Japan captured most of the votes. Shigeru Yoshida became prime minister in Shidehara's wake.

Shidehara joined the Liberal Party a year later, after Prime Minister Tetsu Katayama formed a socialist government. As one of Katayama's harshest critics, Shidehara was elected speaker of the House of Representatives. He died in this post in 1951.

Honours

[edit]From the Japanese Wikipedia article

Peerages

[edit]- Baron (7 September 1920)

Japanese

[edit]- Grand Cordon of the Order of the Sacred Treasure (19 August 1914; Second Class: 24 August 1911)

- Grand Cordon of the Order of the Rising Sun (7 September 1920)

- Grand Cordon of the Order of the Rising Sun with Paulownia Flowers (12 December 1931)

Foreign

[edit]- Grand Officer of the Order of Saints Maurice and Lazarus (Kingdom of Italy; 18 June 1914)

- Knight Grand Cross of the Order of Orange-Nassau (Netherlands; 12 November 1915)

- Order of the British Empire (United Kingdom; 3 July 1917)

- Grand Cordon of the Order of Leopold (Belgium; 11 July 1925)

- Grand Cross of the Order of the Sun (Peru; 24 August 1926)

- Grand Cross of the Legion of Honour (France; 1 April 1927)

- Grand Cross of the Order of the White Lion (Czechoslovakia; 7 February 1928)

- Grand Cross of the Order of the White Elephant (Siam; 26 September 1931)

- Grand Cross of the Order of Menelik II (Ethiopia; 24 December 1931)

- Grand Cross of the Order of Merit for National Foundation (Manchukuo; 1 March 1934)

Court order of precedence

[edit]- Sixth rank (10 October 1903)

- Senior sixth rank (27 December 1905)

- Fifth rank (30 March 1908)

- Senior fifth rank (20 September 1911)

- Fourth rank (10 December 1915)

- Third rank (10 November 1922)

- Senior third rank (1 December 1925)

- Second rank (16 February 1931)

- First rank (10 March 1951; posthumous)

Notes

[edit]- ^ "幣原喜重郎 | 三菱グループサイト". www.mitsubishi.com (in Japanese). Retrieved 5 March 2022.

- ^ "Klaus Schlichtmann, A Statesman for the Twenty-First Century? The Life and Diplomacy of Shidehara Kijuuroh (1872-1951)". Archived from the original on 5 May 2016. Retrieved 3 November 2010.

- ^ Nihon dai hyakka zensho. Shōgakkan, 小学館. 1989. 幣原喜重郎. ISBN 4-09-526001-7. OCLC 14970117.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ "TIME Covers". Time. Archived from the original on 10 March 2007. Retrieved 8 January 2013.

References

[edit]- Kenpou daikyuujou ga toikakeru. Kokka shuken no seigen—kakkoku kenpou to hikaku shi nagara (Investigating Article 9. Limitations of national sovereignty—a comparison with other constitutions), The SEKAI (Tokyo, Iwanami), 3 (2006 March, no. 750), pp. 172–83

- Bix, Herbert P. (2001). Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan, Harper Perennial. ISBN 0-06-093130-2

- Brendon, Piers (2002). The Dark Valley: A Panorama of the 1930s. Vintage; Reprint edition. ISBN 0-375-70808-1

- Dower, John W. (2000). Embracing Defeat: Japan in the Wake of World War II, W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-32027-8.

- Schlichtmann, Klaus (1995). 'A Statesman for The Twenty-First Century? The Life and Diplomacy of Shidehara Kijûrô (1872–1951)', Transactions of the Asiatic Society of Japan, fourth series, vol. 10 (1995), pp. 33–67

- Schlichtmann, Klaus (2001). 'The Constitutional Abolition of War in Japan. Monument of a Culture of Peace?'‚ Internationales Asienforum – International Quarterly for Asian Studies, vol. 32 (2001), no. 1–2, pp. 123–149

- Schlichtmann, Klaus (2009). Japan in the World: Shidehara Kijűrô, Pacifism and the Abolition of War, Lanham, Boulder, New York, Toronto etc., 2 vols., Lexington Books.

- Schlichtmann, Klaus, "Article Nine in Context – Limitations of National Sovereignty and the Abolition of War in Constitutional Law" The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 23-6-09, 8 June 2009. - See more at: http://japanfocus.org/-klaus-schlichtmann/3168#sthash.6iVJNGnx.dpuf

- Shiota, Ushio (1992). Saigo no gohoko: Saisho Shidehara Kijuro, Bungei Shunju. ISBN 4-16-346380-1

- Takemoto, Toru (1979). Failure of Liberalism in Japan: Shidehara Kijuro's Encounter With Anti-Liberals, Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 0-8191-0698-4

- 1872 births

- 1951 deaths

- 20th-century prime ministers of Japan

- Speakers of the House of Representatives (Japan)

- Japan Progressive Party politicians

- Deputy prime ministers of Japan

- Foreign ministers of Japan

- People from Kadoma, Osaka

- Kazoku

- University of Tokyo alumni

- Ambassadors of Japan to the United States

- Ambassadors of Japan to the Netherlands

- Grand Crosses of the Order of the White Lion

- Politicians from Osaka Prefecture

![From left to right: Robert Woods Bliss, Robert Coontz, Kanji Kato, Kunishige Tanaka [ja], Andre Brewster at the Washington Conference on 24 October 1921.](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/56/Japanese_Delegation_arrived_October_24th%2C_1921.jpg/234px-Japanese_Delegation_arrived_October_24th%2C_1921.jpg)