Skipjack-class submarine

USS Skipjack

| |

| Class overview | |

|---|---|

| Builders | |

| Operators | |

| Preceded by | Skate class |

| Succeeded by | |

| Built | 1956–1961 |

| In commission | 1959–1990 |

| Completed | 6 |

| Lost | 1 |

| Retired | 5 |

| General characteristics | |

| Type | Nuclear-powered fast attack submarine |

| Displacement | |

| Length | 251 ft 8 in (76.71 m) |

| Beam | 31 ft 7.75 in (9.6457 m) |

| Propulsion | 1 S5W reactor, geared steam turbines (15,000 shp (11,000 kW)), 1 shaft[1] |

| Speed | |

| Range | unlimited except by food. |

| Test depth | 700 ft (210 m)[1] |

| Complement | 93 |

| Armament |

|

The Skipjack class was a class of United States Navy nuclear submarines (SSNs) that entered service from 1959 to 1961. This class was named after its lead boat, USS Skipjack. The new class introduced the teardrop hull and the S5W reactor to U.S. nuclear submarines.[1][2] The Skipjacks were the fastest U.S. nuclear submarines until the Los Angeles-class submarines, the first of which entered service in 1974.

Design

[edit]

The Skipjacks' design (project SCB 154)[3] was based on the USS Albacore's high-speed hull design. The hull and innovative internal arrangement were similar to the diesel-powered Barbel class that were built concurrently. The design of the Skipjacks was very different from the Skate-class submarines that preceded the Skipjacks. Unlike the Skates, this new design was maximized for underwater speed by fully streamlining the hull like a blimp. This required a single screw aft of the rudders and stern planes.[why?] Adoption of a single screw was a matter of considerable debate and analysis within the Navy, as two shafts offered redundancy and improved maneuverability.[4] The so-called "body-of-revolution hull" reduced her surface sea-keeping, but was essential for underwater performance. Also like Albacore, the Skipjacks used HY-80 high-strength steel, with a yield strength of 80,000 psi (550 MPa), although this was not initially used to increase the diving depth relative to other US submarines. HY-80 remained the standard submarine steel through the Los Angeles class.[5]

Another Barbel-like innovation was the combination of the conning tower, control room, and attack center in one space. This was continued in all subsequent US nuclear submarines. Combining the functions in one space was facilitated by the adoption of "push-button" ballast control, another feature of Albacore.[4] Previous designs had routed the trim system piping through the control room, where the valves were manually operated. The "push-button" system used hydraulic operators on each valve, remotely electrically operated (actually via toggle switches) from the control room. This greatly conserved control room space and reduced the time required to conduct trim operations. The overall layout made coordination of the weapons and ship control systems easier during combat operations.[citation needed]

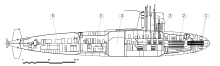

1. Sonar arrays

2. Torpedo room

3. Operations compartment

4. Reactor compartment

5. Auxiliary machinery space

6. Engine room

Much of the overall internal arrangement was continued in the subsequent Thresher- and Sturgeon-class submarines. The Skipjacks' five compartments were called the Torpedo Room, Operations Compartment, Reactor Compartment, Auxiliary Machinery Space (AMS), and Engine Room. With the addition of a missile compartment, the arrangement of the first 41 US nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs) was similar. The design was primarily single-hull, with a double hull around the torpedo room and AMS for ballast tanks. The design was improved on the Threshers, the one-off Tullibee, and subsequent attack submarines by relocating the torpedo room into the operations compartment via angled midships torpedo tubes to make room for a large sonar sphere in the bow. The George Washington class, the first SSBNs, were derived from the Skipjacks, with USS George Washington (SSBN-598) rebuilt from the incomplete first Scorpion. The hull of Scorpion was laid down twice, as the original hull was redesigned to become the George Washington. Also, the material for building Scamp was diverted into building Theodore Roosevelt, which delayed Scamp's progress.[citation needed]

The bow planes were moved to the massive sail to cut down on flow-induced noise near the bow sonar arrays. They were known as sail planes (fairwater planes). The Skipjacks were the first class built with sail planes; they were later backfitted on the Barbels. This design feature would be repeated on all U.S. nuclear submarines until the improved Los Angeles-class submarine, the first of which was launched in 1988. The small "turtleback" behind the sail was the exhaust piping of the auxiliary diesel generator.[citation needed]

The Skipjacks also introduced the S5W reactor to U.S. nuclear submarines. It was known as ASFR (Advanced Submarine Fleet Reactor) during development.[6] The S5W was used on 98 U.S. nuclear submarines of 8 classes and the first British nuclear submarine, HMS Dreadnought, making it the most-used US Navy reactor design to date.[citation needed]

The design of the prototype HMS Dreadnought is closely related to the Skipjack class. The entire aft section of HMS Dreadnought was identical to the Skipjack class as the hull was built around the reactor and could not be changed but the fore section was based on earlier British studies into nuclear submarine design, great care had to be taken to marry the two designs alignment.[7]

Service

[edit]Skipjack was authorized in the FY 1956 new construction program and commissioned in April 1959. Each hull cost around $40 million. Skipjack was certified as the "world's fastest submarine" after initial sea trials in March 1959, although the actual speed attained was classified. The Skipjacks remained the fastest US nuclear-powered submarines until the first of the Los Angeles class entered service in 1974. This was due to the increased size of the Thresher and Sturgeon classes, which retained Skipjack's S5W power plant, plus the introduction of the skewback screw, which was quiet but mechanically inefficient.[8] The Skipjacks saw service during the Vietnam War and most of the Cold War. The Skipjack-class submarines were withdrawn from service in the late 1980s and early 1990s except for Scorpion, which sank on 22 May 1968 southwest of the Azores while returning from a Mediterranean deployment, with all 99 crewmembers lost.[9]

Boats in class

[edit]The gap in the hull-number sequence was taken by the two one-of-a-kind submarines USS Triton (SSRN-586) and USS Halibut (SSGN-587).

| Name | Hull number | Builder | Laid Down | Launched | Commissioned | Decommissioned | Period of service | Fate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skipjack | SSN-585 | Electric Boat | 29 May 1956 | 26 May 1958 | 15 April 1959 | 19 April 1990 | 31.0 | Recycled via the nuclear Ship and Submarine Recycling Program 1 September 1998. |

| Scamp | SSN-588 | Mare Island Naval Shipyard | 23 January 1959 | 8 October 1960 | 5 June 1961 | 28 April 1988 | 26.9 | Recycled via the nuclear Ship and Submarine Recycling program 9 September 1994. |

| Scorpion | SSN-589 | Electric Boat | 20 August 1958 | 29 December 1959 | 29 July 1960 | — | 7.8 | Lost with 99 crewmembers between 22 May and 5 June 1968, 400 nautical miles (740 km) southwest of the Azores in the North Atlantic Ocean, cause unknown |

| Sculpin | SSN-590 | Ingalls Shipbuilding, Pascagoula, Mississippi | 3 February 1958 | 31 March 1960 | 1 June 1961 | 3 August 1990 | 29.1 | Recycled via the nuclear Ship and Submarine Recycling program 30 October 2001. |

| Shark | SSN-591 | Newport News Shipbuilding | 24 February 1958 | 16 March 1960 | 9 February 1961 | 15 September 1990 | 29.6 | Recycled via the nuclear Ship and Submarine Recycling program 28 June 1996. |

| Snook | SSN-592 | Ingalls Shipbuilding, Pascagoula, Mississippi | 7 April 1958 | 31 October 1960 | 24 October 1961 | 14 November 1986 | 25.0 | Recycled via the nuclear Ship and Submarine Recycling program 30 June 1997. |

See also

[edit]- List of submarines of the United States Navy

- List of submarine classes of the United States Navy

- List of lost United States submarines

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Friedman, Norman (1994). U.S. Submarines Since 1945: An Illustrated Design History. Annapolis, Maryland: United States Naval Institute. pp. 128–133, 243. ISBN 1-55750-260-9.

- ^ a b Bauer, K. Jack; Roberts, Stephen S. (1991). Register of Ships of the U.S. Navy, 1775-1990: Major Combatants. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. p. 286. ISBN 0-313-26202-0.

- ^ Friedman, pp. 258

- ^ a b Friedman, pp. 31-35

- ^ Friedman, pp. 56, 130

- ^ Friedman, pp. 125-126

- ^ "Dreadnought Submarine".

- ^ Friedman, pp. 142-143

- ^ On Eternal Patrol postwar page including Scorpion

Further reading

[edit]- Gardiner, Robert and Chumbley, Stephen, Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1947-1995, London: Conway Maritime Press, 1995. ISBN 1-55750-132-7.

- Hutchinson, Robert, Jane's Submarines, War Beneath The Waves, From 1776 To The Present Day, Harper Paperbacks, 2005. ISBN 0-06081-900-6.

- Polmar, Norman (2004). Cold War Submarines: The Design and Construction of U.S. and Soviet Submarines, 1945-2001. Dulles: Brassey's. ISBN 978-1-57488-594-1.